One Million Dollars in Three Months: A Hefty Bill for Election Propaganda on Social Media in Iraq

Sherif Murad

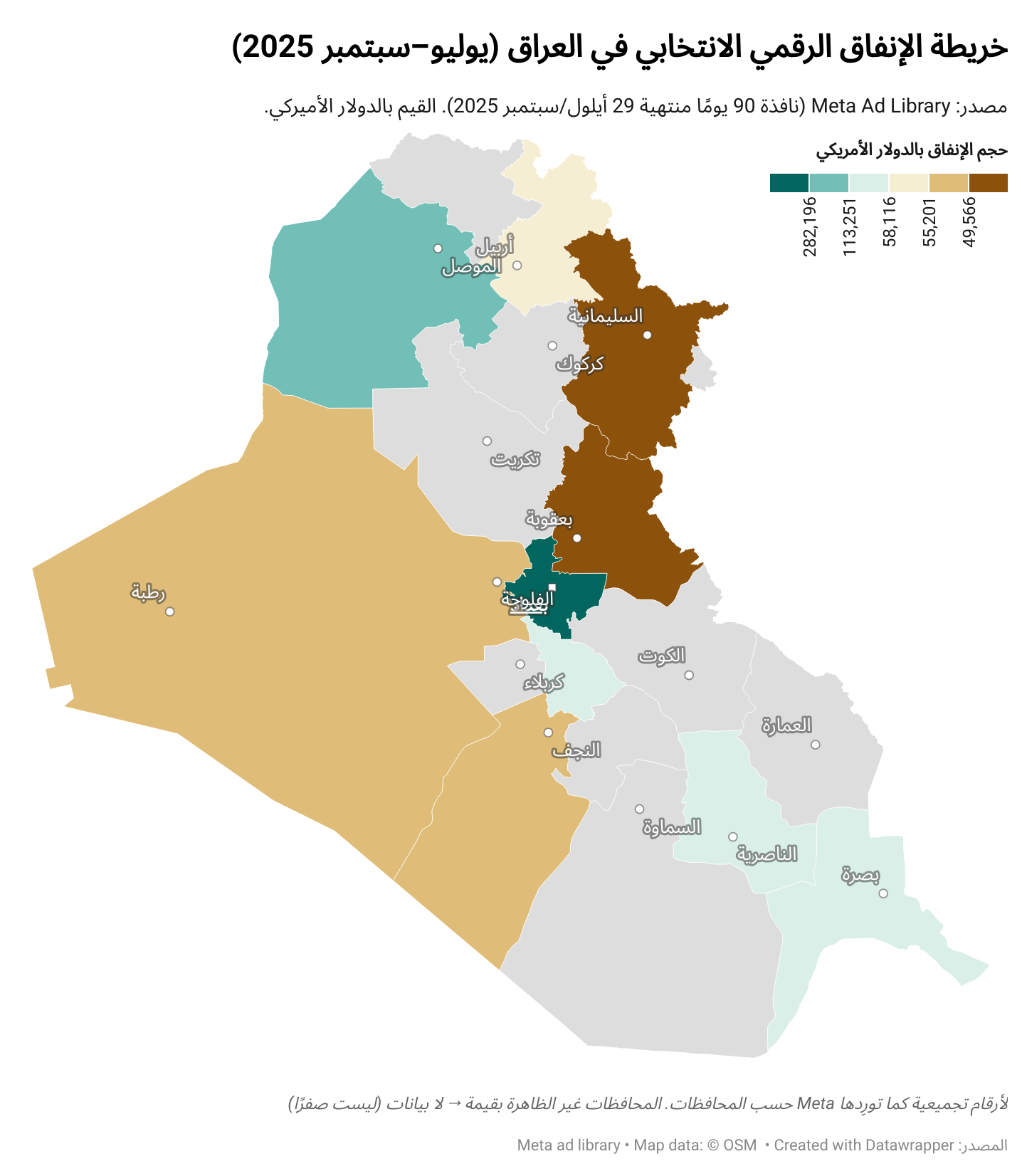

Between July and September 2025, Iraqi political forces and public figures spent more than one million US dollars on sponsored ads on Facebook and Instagram, according to Meta’s data. Significantly, 60% of this expenditure originated from pages that did not disclose any political affiliation. Arabi Facts Hub monitored the pages advertising the Iraqi elections to analyze the nature of their content.

In Iraq, the competition for council and governorate seats has moved from traditional venues like public squares and speeches to social media, making the small screen of a voter's phone the constant and main battlefield for influence and persuasion. Between early July and the end of September 2025, political entities, local groups, and individual figures spent around one million US dollars on sponsored ads on Facebook and Instagram, according to official data from Meta’s Ad Library, which monitors political advertising in each country—even before official election campaigns had begun.

Over 60 percent of this expenditure originated from pages that obscure their political leanings and fail to disclose the funding entity in the "Paid for by" section. In other words, the largest portion of election-related money in Iraq’s digital space is moving without an identity, even though the content is clearly targeted and geographically directed at the provinces with the most heated electoral competition.

This investigation relied on Meta’s reports for the past 90 days (aggregated figures by province and by categories of funders), in addition to detailed ad files obtained in early November. In the detailed files, spending was calculated based on the average range of each ad. The texts were automatically classified (Arabic/Kurdish) as direct/indirect, then manually reviewed. Any partisan affiliation that was not supported by clear public evidence was kept as “unclassified.”

A General View of the Digital Electoral Arena

Baghdad tops the digital spending map with about $282,000 in just three months, which is close to a third of total digital electoral spending in Iraq, followed by Nineveh with nearly $113,000, then Dhi Qar and Basra with about $60,000 each, followed by Babylon, Erbil, and Najaf with figures ranging between $50,000 and $58,000.

Meta data also shows that politically less weighty provinces, such as Al Qadisiyyah, Wasit, and Babylon, were not absent but received less spending.

The analysis does not just reveal the volume of money, but the absence of affiliations; more than 60 percent of this spending came from pages that do not disclose any party affiliation or funding source in the "Paid for by" box, meaning that the largest bloc of digital electoral campaigns operates with an anonymous identity but carries a clear directional message.

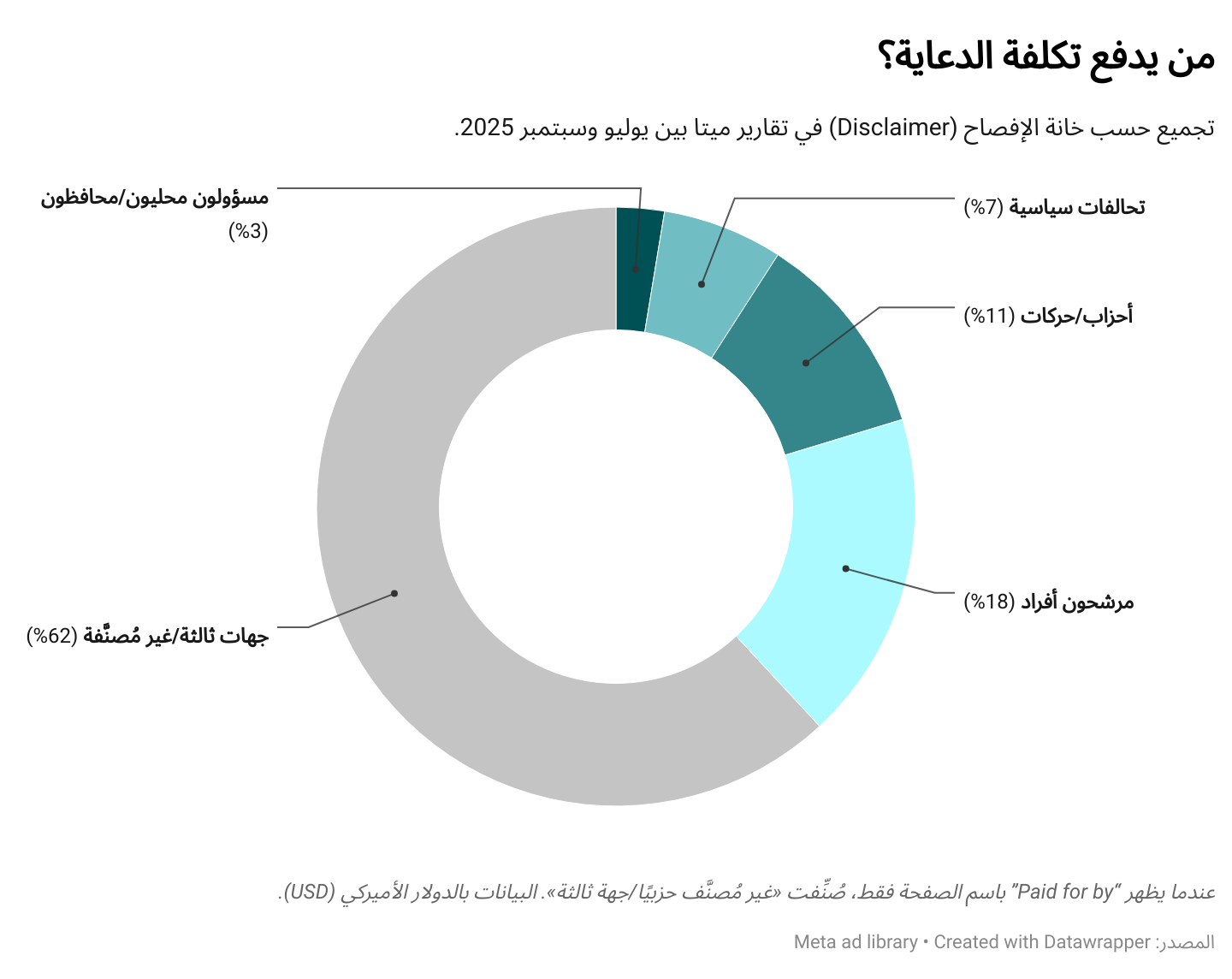

Tracing the sources of this money makes it clear that the digital market is managed by parties that are not necessarily partisan or known to the public. Unclassified pages spent approximately $600,000, significantly ahead of individual candidates (about $173,000) and political parties ($109,000), while the remainder was distributed among alliances ($63,000) and local officials ($25,000).

As for the discourse, a reading of hundreds of funded texts showed that digital propaganda does not promote political programs or projects as much as it markets narratives of affinity, trust, and belonging. In the south and center, the dominant discourse is tribal and social, often with a religious or values-based tone, invoking local symbols and building legitimacy from social proximity rather than political content.

In major urban cities, the language of achievement, service, and development prevails, while some candidates adopt an executive tone that focuses on efficiency and projects.

In the northern governorates, the discourse tends towards a direct electoral format, using names, numbers, and symbols, in clear Kurdish language targeting a specific geographical and linguistic audience.

Public Pages as Political Facades

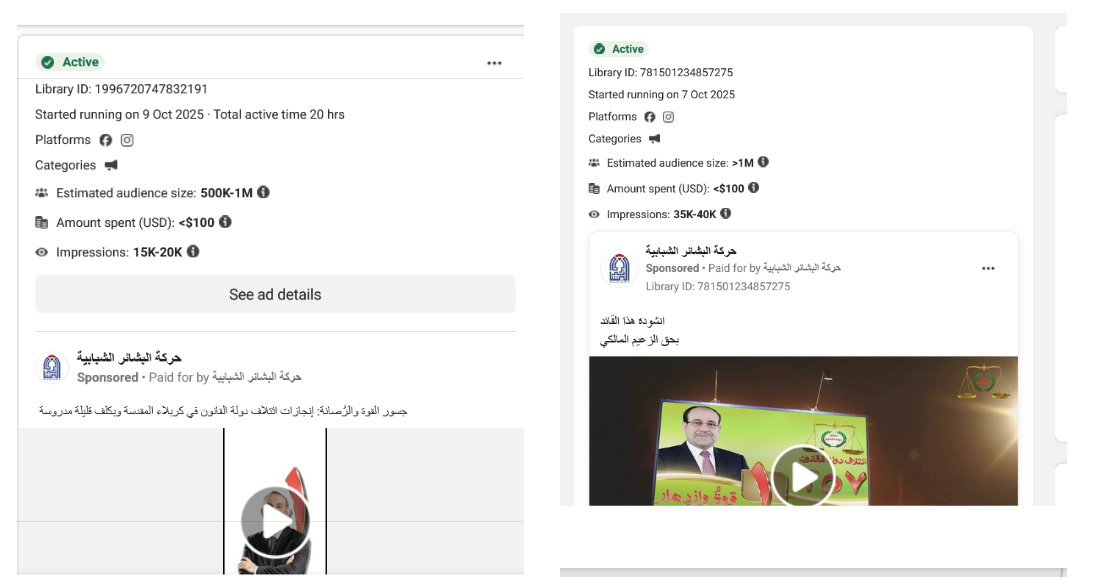

Dozens of Iraqi pages on Facebook appear to be neutral news or community platforms, but tracking the sponsored advertisement data reveals that many of them engage in disguised electoral propaganda, serving specific political parties without explicitly announcing it.

In the detailed sample we analyzed during the first week of October 2025, pages such as "Multaqa al Basha'er" (Glad Tidings Forum), "Bukhari Jamil," "Multaqa al Iraq al Arabi" (The Arab Iraq Forum), and "Al Iraq Yajma'una" (Iraq Unites Us) stood out among the highest spenders in Baghdad and the South, within the category of "Unspecified sponsor." This category alone accounted for more than half of the digital electoral spending in Iraq.

It is estimated that this network of public pages spent nearly $600,000 during the last three months, distributed among news posts with headlines about "meetings," "visits," and "service projects." However, in their content, they regularly promote specific figures from the Coordination Framework, or executive personalities close to traditional Shiite groups.

Notably, the advertisements themselves do not talk about elections or voting, but rather about "stability," "completed projects," and "loyalty to the nation"—phrases that reproduce the official discourse.

By matching the texts with spending data and targeted areas, it appears that these pages focus on Baghdad, Basra, Karbala, and Dhi Qar—the governorates witnessing intense competition between the Coordination Framework and independents.

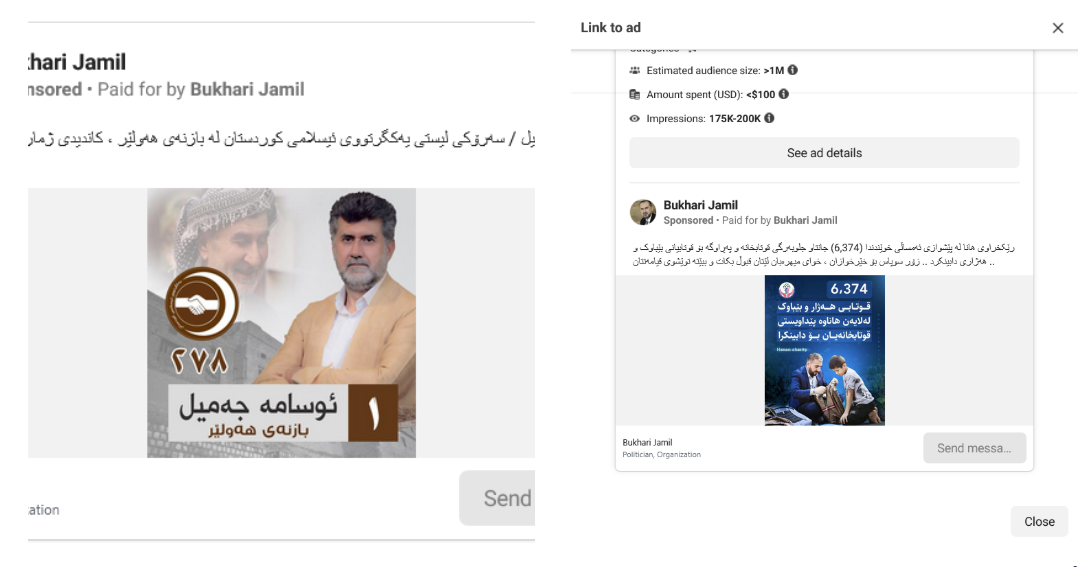

The page "Bukhari Jamil," which presents itself as a cultural and social page, published repeated advertisements during the first week of October with semi-identical texts. These included pictures of local leaders from the same current, and symbolic references to "Loyalty," "Truth," and "Authenticity," which are familiar terms in the tribal propaganda that the Coordination Framework usually relies on to mobilize its base.

Linguistic analysis of the texts shows that more than 70 percent of the content of these advertisements indicates positive mobilization discourse directed towards a supportive base, not towards persuading the undecided; meaning they are internal mobilization advertisements more than competitive electoral advertisements.

The "Al Basha'er Forum", which maintains a wide popular base in the South and Baghdad, uses a more professional method of concealment. The page does not indicate any party affiliation, but it produces promotional video materials that match the content and style of clips broadcast by channels close to the State of Law Coalition; some clips are even reposted verbatim on the accounts of figures associated with the coalition.

The page is verified, and Ad Library screenshots show that the advertisements are Paid for by: Al Basha'er Youth Movement, without showing a partisan entity behind it, which keeps the political affiliation editorially unclassified.

The same thing was repeated with other pages publishing in the Kurdish language, where local media channels are used as a front for the propaganda of well-known Kurdish parties, especially in Erbil and Sulaymaniyah, but without indicating direct party funding.

For example, advertisement data during the first week of October showed repeated spending from pages, such as "Roj News" and "Zanko Media," on posts that included pictures and messages of candidates from the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP) and the Change Movement (Gorran), in a clear Kurdish language targeting the audience in Erbil and Sulaymaniyah.

These advertisements, with budgets ranging between four and nine thousand dollars for each page during a short period, did not include any identification of the funding entity in the "Paid for by" field, despite promoting direct political content (names of lists, candidate numbers, or party slogans).

These media platforms thus act as soft fronts for election propaganda, as the party discourse is funded by means that appear to be neutral media but which recycle the same political messages.

Money in the Shadows

The digital propaganda market appears straightforward, composed of pages for alliances, parties, and candidates, as well as accounts for local officials. Yet, by reassembling the numbers from Meta's data, it is evident that the largest contributor does not disclose its political affiliation.Over the last 90 days, the unidentified pages spent nearly $600,000, which is about three times what the parties and movements combined spent ($109,000), and more than the spending of individual candidates ($173,000).

An example of this is the "Multaqa Al Basha'er" page, which has been publishing content since 2021 that leans toward the State of Law Coalition/Framework, through a service-oriented discourse that is not party-directed. Its total spending on targeted ads reached nearly $37,000, with heavy targeting of Baghdad and the South.

As for the group of Kurdish pages that publish direct electoral content - led by "Bukhari Jamil" - their total spending reached about $18,000 during the study period, according to Meta's data.

These pages publish material in Kurdish that includes list numbers and party slogans, but they do not refer to party affiliation in the advertisement texts.

Also classified were media pages within the "Unidentified" bloc—that is, pages that do not disclose a party or alliance in the "Paid for by" field—such as "Roj News," "Zanko Media," and "Erbil 24." These platforms present themselves as local news channels but fund content directed at a specific Kurdish audience in the Kurdistan Region.

These pages are geographically distributed, with Baghdad coming first with about $282,000 of the total national expenditure over 90 days, followed by Nineveh with about $113,000, and then the southern governorates—Dhi Qar, Basra, and Babylon—with amounts ranging between $58,000 and $62,000 each.

The narrative is shaped according to the geographical areas: in Baghdad, the narrative of power, prestige, and achievement is promoted; in the South, the legitimacy of social and religious proximity is marketed; and in the North, direct electoral discourse appears in a local language and identity.

Notably, two-thirds of the spending is channeled through unclassified means, while transparency from both the platform and regulatory bodies is alarmingly minimal.

The data we monitored represents the first wave before the peak of the campaign, and it is likely that the coming weeks will witness a doubling in the volume of spending and an expansion in the scope of messages. As the polling date approaches, it will become necessary to track whether these "unidentified" networks will recycle their discourse in a clearer form, or continue to operate in the shadows to determine voting trends.