MDM/Info Disorder in MENA: Insights, Patterns, and Emerging Trends in the Era of AI

Executive Summary

This report analyzes the Misinformation, Disinformation, and Malinformation (MDM) space, also referred to as Information Disorder, within the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region while considering the rise of generative AI. The report attempts to answer key research questions such as understanding the scale of MDM in MENA, identifying who is behind them, and identifying emerging patterns and trends from multifaceted perspectives. Additionally, the report highlighted the role of AI and what key players in MENA we should keep an eye on, for those countering the information disorder.

We applied a combination of quantitative and qualitative research methods on AFH’s fact-checked posts database as well as our series of publications called Eye on Twitter. The combined analysis covered campaigns and posts published between 2021 and the end of Q3 in 2023. Our fact-checked posts database and publications cover stories that involve multiple platforms and actors. Our research and findings focus on Egypt mainly, and to a lesser extent, Lebanon, Iraq, Jordan, and Yemen. Additionally, we conducted a literature survey focusing on the practical side of MDM using some of the well-documented incidents and campaigns across MENA that spanned the period from 2011 until 2023.

The research report explores the scale of MDM in MENA, how it is evolving over time, and whether it is becoming a full-fledged, mature industry and sense the maturity level of the ecosystem. It is also seeking to understand the key actors behind MDM campaigns in MENA and whether new types of actors are getting more involved in driving the information disorder.

It analyzes the key drivers behind MDM as well as the main tactics applied in MENA. The report discusses some tactics in detail, some newly emerging tactics and compiles others into the appendix. The study also focuses on MENA’s fact checkers and captures emerging patterns in their operations, driven by fact checkers and by the surrounding ecosystem.

The study lists the key themes/topics targeted by MDM campaigns in MENA based on AFH data. It also analyzes the key themes that drive online MDM in MENA towards physical harm.

Finally, the study surveys available literature and identifies trends on the role of AI in media and journalism in MENA, and how MDM is going to be affected by the rise of GenAI. A list of benevolent players in Media and AI who can be part of mitigating the MDM risks in MENA was created.

This report draws from pioneering research titled “Meeting the Challenges of Information Disorder in the Global South,” [1] led by Professor Herman Wasserman, which maps the actors currently leading the counter-information disorder, and their approaches, tools, and methods. Furthermore, it studies the research landscape and identifies key areas for further research. Our report focuses on those creating the information disorder in MENA, their tactics, and how they exploit some of the challenges identified by Wasserman’s research in the counter-information disorder ecosystem.

The following are selected key findings highlighted by this research study:

Key findings on the scale of MDM in MENA:

- General increase in the scale of MDM campaigns over the years in MENA and campaigns are becoming highly coordinated and multifaceted with the involvement of state and nonstate actors. This is not limited to MENA or the Global South, as MDM/Info Disorder is a global challenge, but MENA’s campaigns have specific features influenced by existing deep structures, like ruling systems, social formations, the relationship between the state and society, and many others

- Top-down disinformation, i.e. coming from reputable and influential figures in the society, as opposed to bottom-up, i.e. driven by bots and troll armies, is becoming more common in MENA. This can be seen in the MDM campaigns we analyzed, which were activated or amplified by famous Arab influencers

- Depending on the country’s governance maturity and rule of law, the possibility of digital MDM campaigns to drive physical harm against targeted groups in some MENA countries is rising. Such a possibility increases in MENA failed-states and war-torn countries. On the other hand, legislation criminalizing the publication of misleading information in some Arab countries “has been used to suppress freedom of expression” [2] . Hence, both existence and absence of regulations could be used against dissidents

- Globalization and wide access to technology among MENA youth are factors that potentially explain how some MDM campaigns can travel across physical and digital borders and become regional. Polarized masses with ideological worldviews who are being exposed to identity politics discussions in the West are mobilized. Our analysis showed this across different MENA countries like Yemen and Lebanon

- Although politics is still the most significant topic being used in MDM related content, other topics like the economy, environment, science, and technology are on the rise in Egypt specifically

- Sports-related MDM in Egypt is most likely widely used as a vehicle to gain higher reach and consequently financial gains by rogue page admins and account owners

- MENA’s MDM actors do not seem to have integrated the Generative AI in their MDM campaigns to a scalable level yet!

Key findings on MDM actors in MENA:

- State actors or state-backed actors in specific MENA countries have generally two involvement strategies in MDM campaigns: overt, where they have invested in state resources and private sector companies to conduct the campaigns, and covert, where they push MDM campaigns through: informal media arms, opposition (of the targeted country) living in exile, and public relation firms

- On the sports-related MDM campaign, we noticed a few campaigns where “sportswashing” was used to target MENA audiences. However, sportswashing MDM is currently used more by MENA governments when targeting global audiences, like Saudi Arabia, UAE, and Qatar

- Patterns that evolve differently in MENA countries for the same regional campaign magnify the variances in social structures, governance models, and rule of law across MENA countries, which show that MDM drivers run deeper than previously thought and calls for dedicated MENA-wide comparative analysis to understand the differences at a country level. This can be seen in campaigns we analyzed including those targeting the LGBTQ community that spanned Lebanon, Yemen, and Iraq

- There is a rise in recycling extremists’ “Western” rhetoric/narratives and repackaging it for Arabic audiences to legitimize the MDM campaigns. This can be seen in campaigns targeting women and LGBTQ community in MENA where specific conservative and sometimes conspiratorial content by well-known Western media commentators or philosophers was used

- The wide adoption of specific content production means, like live stream videos, is leading to content that is difficult to fact-check, especially when the publishing pace is faster than any fact-checking operations. This is especially becoming harder in campaigns where some live streamers claim to be relatives or close to victims being targeted by MDM campaigns

- Lack of visionary regulations and transparency in MENA usually excludes a key stakeholder in the ecosystem: the general public. This willful blindness usually backfires on the whole ecosystem and continues to facilitate MDM campaigns by various actors

- Although platform owners are making it difficult to game the algorithms by profit- and reach-seeking actors, some of these changes are still enabling more MDM campaigns to flourish. Studying such changes as well as the media business models in MENA that drive MDM campaigns is imperative, and AFH will be working on this in future research

Key findings on MDM tactics in MENA:

- The tactic of “disinformation through mistranslation” could potentially be on the rise in certain types of campaigns targeting the MENA region, especially regarding incidents that have global attention

- Multi-staged, cross-platform, and “fusion” of MDM tactics in MENA are on the rise, increasing the sophistication level and pervasiveness.

- While Generative AI seems not yet integrated in existing MDM campaigns operations in MENA, the continuous streamlining of GenAI tools will enable the actors to build scalable pipelines with higher automation and orchestration capabilities. Also, this can advance the severity level of existing tactics like ephemeral disinformation on multiple platforms (systemic deletion of MDM published content)

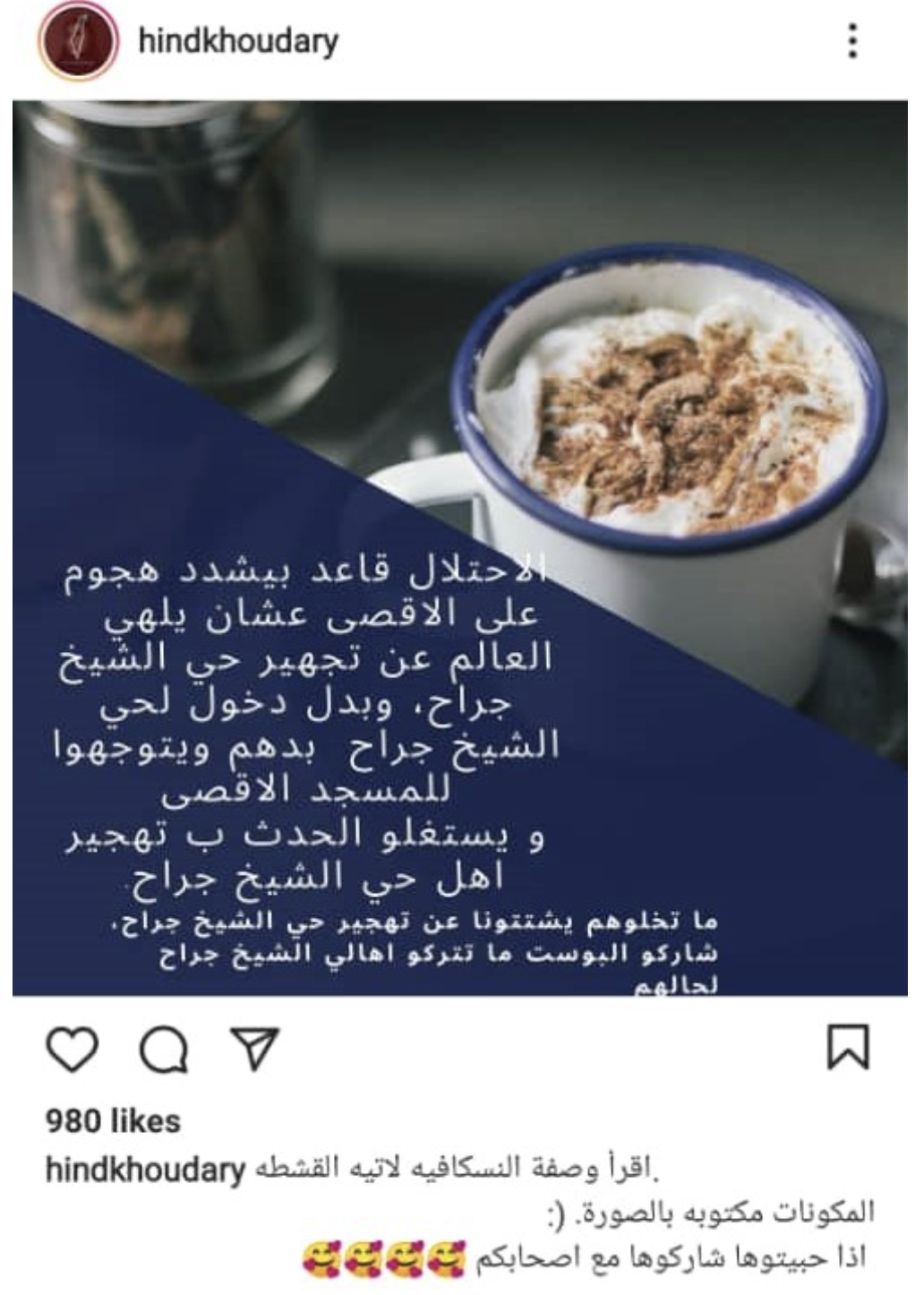

- Innovative approaches to bypass systemic censorship of pro-Palestine content on Instagram and Facebook could potentially be abused by MDM campaign actors

- “Deceiving with statistics” continues to be a favored MDM tactic in countries like Egypt. This can be seen in the campaigns we analyzed in this study, especially those involving statements made by Egyptian officials.

Recommendations and What’s Next!

To MENA Fact Checkers

- Coordinate your efforts with other MENA fact checkers, as many MDM campaigns are not confined within single-country borders. Develop collective initiatives and fact checking campaigns on common themes and events. Connect with fact checking peers from the Global South and establish communities of practice to share experience, tools, ideas and resources.

- Publish datasets and MDM tactics repositories with the public to promote data democratization and encourage further research to be conducted.

- Invest in technical tools and AI, especially generative AI. Reach out to universities and the private sector to have partnerships, research grants, and any form of beneficial collaboration. Work with them to create MDM tracking tools and technologies to analyze real-time voice/video content, and study and analyze MDM on widely used platforms like Telegram and Discourse

- Reach out to developer conferences and build direct relationships with the development communities in your country and abroad. Incentivize them with ideas, challenges you are facing, and share your data with them. Participate in hackathons and seminars within those communities.

- Engage with the public and invest in prebunking activities. Visit schools, universities, and public spaces to promote what you do.

- Develop shared vision on information disorder covering MENA. Address key questions like: why are we contouring MDM? Is it a lost battle given the resources in the hands of perpetrators? Is it a zero-sum game or at least we can make MDM creation a bit difficult for culprits?

- Map the MDM ecosystem in MENA and devise ways for collaboration between independent fact checkers and those backed/funded by local governments. Identify what goals and endeavors can be mutually worked on and what lines should not be crossed. Identify collective initiatives like countering lucrative business models that promote MDM in the private sector.

- Conduct periodical knowledge sharing sessions and design Information Disorder Strategy that covers MENA and can be implemented by each fact checking agency. Design the governance, operating model, people & culture, technology, and data aspects of the strategy. Measure the strategy implementation progress and share insights with decision makers in the ecosystem.

To MENA Governments

- Curb the proliferation and weaponization of information disorder by adopting clear regulations and laws that penalize such acts.

- Fund research and offer grants that focus on the MDM studies not only from a technical point of view, but from the deep-structures views, too (including political, economic, social, and other structural factors).

- Include the risk of MDM in the country’s National Strategy and design policies and initiatives to treat MDM as a national threat.

- Involve civil society and fact checkers in the designing regulations and enforcing them. MDM is a threat to everyone and countering it is a collective effort.

- Scrutinize perpetrators from the private sector who exploit the public and use deceptive methods like recruiting social media influencers to conduct disinformation campaigns.

- Empower independent fact checkers and adopt a mindset that welcomes their freedom of speech and expression as they are playing a vital role in protecting the society.

- Adjust legislation criminalizing the publication of misleading information in a way that disables potential use of the same legislation to suppress freedom of expression.

- Mandate committees and regulators to oversee and hold abusers accountable and publish data to enable further research. Work with platforms through their regional offices to share information on perpetrators and offer it to researchers.

- Review and assess algorithms used by platforms for potential MDM abuse. Empower local tech startups to create innovative solutions for fighting information disorder.

- Scrutinize social media platforms to make sure they comply with their code of conduct and local/global data privacy standards.

- Create and participate in global forums and work with foreign governments to share large-scale ideas and mitigation plans to counter this threat.

- Invest in raising the public awareness on the threat of information disorder. Work with partners in the civil society and fact checking ecosystem on national plans and projects to immunize the public from local, regional, and global MDM campaigns.

Introduction

Arabi Facts Hub is a nonprofit organization dedicated to researching information disorder in Arabic content on the Internet and providing innovative solutions to detect and identify it. Information disorder can be described as publishing false information without the intent of harming, like misinformation, or with the intent of harming like disinformation and malinformation (MDM). This study refers to information disorder and MDM interchangeably.

In our first research report, we studied the MDM space covering the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. This was done while considering the rise of generative AI. We focused on the offensive side of the ecosystem by trying to answer the following questions:

- What is the scale of MDM in MENA?

- Who is behind the MDM in MENA?

- What are the drivers behind MDM in MENA?

- What are the key MDM tactics in MENA?

- What are the key themes/topics targeted by MDM campaigns in MENA?

- Can online MDM in MENA lead to physical harm?

- What is the role of AI in media and journalism in MENA? How is MDM going to be affected by the rise of GenAI?

Then, we moved to the defensive side of the ecosystem and highlighted the emerging patterns among MENA actors and who are the key players in Media & AI in MENA that we should keep an eye on, for those countering the information disorder.

We relied mainly on AFH’s fact-checked posts database as well as our series of publications called Eye on Twitter to conduct this research. The combined analysis covered campaigns and posts published between 2021 and the end of Q3 of 2023, where platforms and involved actors were included in the study. Our research and findings focused on Egypt mainly, and to a lesser extent, Lebanon, Iraq, Jordan, and Yemen. Furthermore, we reviewed well-documented incidents and campaigns across MENA that spanned the period from 2011 until 2023.

As part of this research, we identified areas that needed further exploration and gaps in the Arabic MDM data landscape that should be bridged. AFH aims to play an active role in the MDM research, policy, and data spaces in MENA through publishing more in-depth and data-informed reports.

What is the scale of MDM in MENA?

There is a general agreement that the MDM ecosystem in MENA is alarmingly massive, targeting wide audiences who have relatively high connectivity, device availability, and platform usage trends in that region [3]. Yet, it is very difficult to find an independent research or media report that quantifies the scale of what has likely morphed into a full-fledged MDM industry, with supply and demand dynamics. Probably the obvious reason behind that is the restrictions on freedom of press and expression in MENA, which are needed to uncover one the main actors behind MDM in MENA: Arab regimes[4] Another reason is the fact that MDM and Influence Operations (IO) are secretive and deceptive[5] . There are many IO happening, not just in MENA but worldwide, and people behind it conceal their identities. As a result, we lack sufficient information to easily identify the IO and who orchestrates them. But we can somewhat infer the scale by looking into the known incidents of IO that targeted a specific country in MENA or had a regional scope.

Since Twitter, now X, is one of the main mediums that is targeted by disinformation campaigns in MENA, Twitter Transparency and Twitter Moderation Research Consortium (TMRC) published a public archive of state-backed information operations in October 2018[6] . Soon enough, in September 2019, Twitter announced two MENA-related takedowns. The first one took down a network of 267 accounts based in the United Arab Emirates and Egypt, which were involved in influencing operations targeting Qatar and Iran. This incident highlighted the role of private companies in such operations, as the private company behind these accounts was identified to be an Abu Dhabi and Cairo-based company called DotDev[7] . Simultaneously, Twitter suspended six accounts posing as independent media outlets, yet promoting narratives favorable to the Saudi government. The second takedown involved the removal of 4,258 accounts operating exclusively from the UAE and tweeted mostly about Qatar and Yemen[8] .

Two months following that, in December 2019, Twitter announced the largest state-backed disinformation network it ever detected, which originated from Saudi Arabia. The core network included 5,929 accounts, on which TMRC published comprehensive data. However, these accounts were the tip of the iceberg as they controlled an extended network of 88,000 accounts, all of which were suspended amid the announcement[9] . Twitter was able to trace back all these accounts to a social media and marketing company based in Saudi Arabia called Smaat. As part of this operation[10] , two Saudi nationals linked to the matter, Ali Alzabarah and Ahmed Almutairi/Aljibreen, were charged and listed on the FBI's Counterintelligence Wanted list[11] [12] . This behavior of groups of pages and people working together to mislead others about who they are, their perception, and what they are doing is called Coordinated Inauthentic Behavior (CIB)[13] .

Coordinated disinformation campaigns are not new in MENA, but the 2019 takedowns were the largest, indicating how mature and vicious this industry evolved with time. Probably the earliest documented campaign was initiated from Iran in 2010, targeting Saudi Arabia beside other countries. The operation included 783 Facebook pages, accounts, and groups[14] . Moreover, 2015 witnessed the inception of disinformation campaigns led by two companies: New Waves in Egypt and Newave in the United Arab Emirates[15] . The Disinformation Visualizer project published by the Atlantic Council's DFRLab and Google's Jigsaw showcases the identified coordinated disinformation campaigns globally between 2010 and 2019[16] .

Reviewing the identified CIB MDMs beginning in 2020, it can be noticed that the MDM scale in MENA expanded in terms of regions, amount of published content, and campaigns launched by foreign governments. The Stanford Internet Observatory (SIO) studied many of Twitter's seized accounts managed from Saudi, UAE, and Egypt during that year and concluded that the content was regional and mainly criticized the Syrian government and Iranian influence in Iraq, and promoted Haftar in Libya[17] .

Shortly after that, SIO and Graphika analyzed 99 Pages, 6 Groups, 181 profiles, and 22 Instagram accounts identified by Facebook/Meta to be inauthentic and linked to the Russian Internet Research Agency (IRA). The analysis concluded that they targeted Libya, Syria, and Sudan[18] . Further analysis by SIO showed hundreds of accounts spreading hundreds of thousands of tweets, originating in Iran, and others linked to Russian networks, targeting Arabic-speaking audiences with coordinated disinformation. Many of these accounts were sock puppets and fake personas whom SIO believes they were affiliated with the Internet Research Agency (IRA) and Russian government-linked actors[19] .

Beside the scalability increase in regional targeting, the country-specific targeting among MENA rivalries continued. Some of these campaigns even had "defining characteristics" like the network of 33 fake accounts claimed to be dissident members of the Qatari royal family but turned out to be sock puppet accounts linked to the government of Saudi Arabia. These accounts "repeatedly changed their screen names and deleted earlier tweets" as highlighted by SIO[20] . Some of these campaigns capitalized on nonpolitical topics to push political propaganda, like the network of 9,000 pro–United Arab Emirates network that used Coronavirus hashtags to criticize Turkey’s military intervention in Libya and praise the government of UAE[21] .

Domestic coordinated disinformation campaigns were on the rise, too. A notable takedown was announced by Facebook on August 6, 2020, where Yemen-Based 28 Pages, 15 Groups, 69 Facebook accounts, and ten Instagram accounts were suspended for impersonating government agencies to push anti-Houthi content[22] .

Researchers from Stanford University curated an important dataset documenting all known Facebook and Twitter takedowns centered on Influence Operations (IO) in the MENA region, especially between 2020 and 2021. The dataset contains 46 information operations, originating from ten MENA countries. Iran was the highest with 20 of the 46 takedowns. Egypt was second with 10 takedowns, then the UAE with 6, and Saudi Arabia was fourth with 5. The researchers found that among the 46 takedowns, 24% were linked to a government and 26% were attributed to a marketing, PR, or IT firm[23] . This last finding raises an important question: does the absence of specific countries like Qatar in most of the published disinformation analysis and takedowns imply that they refrain from directly engaging or investing in counter-disinformation campaigns? Or maybe private companies are filling that vacuum by providing propaganda-as-a-service for them and acting as fronts? There is no conclusive answer, but some of AFH's investigations in the next section of this report may provide some leads.

Moving to 2023, and despite the measures taken by major social media platforms to fight MDM, the CIB campaigns continue to flourish and their tactics are advancing. DFRLab published two analyses highlighting some of these tactics. The first analysis was in Sudan which involved the use of nine hundred revived dormant accounts; accounts that became active after years of inactivity, possibly hijacked. These accounts amplified content shared by Sudan’s Rapid Support Force (RSF) and Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, known as Hemedti[24] . The second analysis highlighted how hundreds of thousands of accounts pushed hashtags promoting Egypt’s support for human rights. Essentially, these accounts tried to hijack the narrative and widely acknowledged perception of the poor human rights conditions in Egypt[25] . This activity included running slandering campaigns targeting activists like Gamal Eid[26] .

AFH Research Findings on the Scale of MDM in MENA

Our Open-Source Intelligence (OSINT) team at AFH, in collaboration with Daraj Media, published original analyses covering a wide range of MDM campaigns in MENA, which identified the increasing scale of campaigns and evolving tactics during 2023. These campaigns were selected by the AFH editorial team based on topic significance to regional and global events, the campaigns reach and trend levels, breadth and depth of used platforms and tactics. Some campaigns may appear very local, however, this should be considered with a level of abstraction, as we believe these campaigns’ information disorder dynamics are similar to other campaigns not within MENA countries only, but across the globe.

Jordan

We started with Jordan, where we investigated the role of an online campaign, which included many fake accounts, and how it interfered with the passing of a cybercrime bill in the parliament. Pro-Jordan monarchy tweets in mass numbers flooded twitter as private pictures of the crown prince and his new bride on the beach were leaked. These online campaigns seemed to have set the tone for the discussion around the controversial anti-cybercrime law which was passed in August 2023. These online campaigns seemed to be working in coordination, and 24,000 tweets came from accounts that did not disclose its geographic location. The campaigns operated in 5 main hashtags, involving 10,000 accounts, producing 34,000 tweets, viewed 24 million times, and had a reach of 32.5 million. Retweets were above the average retweet number, which was at 64.5%. This is a sign of coordinated and inauthentic engagement. Engagement with the hashtags from Egypt (465 tweets) contributed to the hashtag, resulting in hashtags showing up on regional trends[27] .

Our analysis showed that this campaign is an example of a coordinated and multifaceted campaign, with the plausible involvement of state and nonstate actors. Moreover, looking into the interaction volume and the number of accounts involved highlights the increase in scale of MDM campaigns over the years in MENA, as such a volume is relatively huge in a country like Jordan.

Lebanon

Moving to Lebanon, AFH OSINT team investigated anti-LGBTQ activity on social media in Lebanon and how it expanded to many Arab countries. The story started after Hassan Nasrallah’s, the Secretary-General of Hezbollah, remarks on ‘standing up to the LGBTQ movement.’ A chain reaction occurred from allies in the region (militias in Iraq and Yemen) amplifying the message. This investigative report looked into organized online campaigns from June 2023 (pride month) to August 2023. Search on words affiliated with LGBTQ terminology soared by 74%. During that same period, there were 248 thousand posts on the topic, with an average of 3.5 thousand tweets daily. These campaigns generated almost a million engagements, on average 14,000 engagements per day.

243,000 out of the 248,000 were on twitter, coming from 34 countries. These tweets were viewed 133 million times on twitter. In June of the same year, the Islamist Sadrist movement in Iraq launched a similar anti-LGBTQ campaign, generating 108,000 tweets, with a reach of 2 million. The report uncovered that 74% of the hashtag activity were retweeted, and only 15.9% of the tweets were original. Nasrallah’s remarks led to a ban in Iraq on the use of the terms (gender) and (homosexuality) in traditional and new media, and instead the use of more inflammatory terms.

AFH analysis highlights the scale that such campaigns can reach especially when ignited by top-down disinformation, i.e., coming from reputable and influential figures in the society. What makes this disinformation campaign unique is its ability to mobilize masses in the real world and incite them to inflict physical harm to marginalized groups.

Yemen

In Yemen, 4 hashtags surfaced after Nasrallah’s remarks. In total, 22,000 tweets were generated with a reach of 4 million. 72.8% of the engagement on the hashtags were inauthentic, and the majority of the tweets came from Yemen, then Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Lebanon, USA, Kuwait, Bahrain, Egypt, China and Syria[28] .

AFH analysis of this campaign highlighted how disinformation can travel physical borders and reach all the way from Lebanon to Yemen. Later, this report will discuss the drivers behind the MDM diffusion and its scalable spread, but in a few words, this campaign highlights how globalization and wide access to technology among MENA youth are possible factors behind the wide participation in these hashtags and the MDM entailed in them. Probably the way this campaign was framed and the fear mongering has resembled an existential threat to a large audience of conservatives, whether socially or religiously. This all played a role in causing the regional spread of this campaign.

Egypt

Moving to Egypt, we investigated the online campaigns that supported a man accused of murdering a woman on camera (Nayyira Ashraf). These campaigns spread misinformation and gender-based violence. After the defendant was convicted of murder, 9 Facebook groups (closed and open groups) were created with a total of 86,000 members. One of the largest groups (with 18,000 members) posted 3,500 posts within a month of its launch. These groups focused on supporting the defendant and claimed to “uncover” the lies against him, influence public opinion with misinformation, and spread conspiracy theories. A hashtag in support of the defendant was generated on twitter, with 41,000 interactions (between tweets, retweets and likes). The investigation names the key groups and accounts involved in this coordinated behavior[29] .

Staying in Egypt, we investigated the Egyptian accounts tweeting in support of a pro-Qatar hashtag. A hashtag surfaced in October 2022 after the German Foreign Minister criticized Qatar for poor human rights conditions in preparation for FIFA world cup 2022. The hashtag grossed 15,000 tweets, 39,900 retweets, and 16,000 likes. Total accounts that participated in the hashtag were 2,039 accounts from countries such as Qatar, Egypt, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Oman and Kuwait.

Some of the most active accounts on the hashtag had affiliations with Muslim Brotherhood and anti-regime views. Other accounts are known for questionable promotion tactics by usually advertising for commercial purposes or being hired to raise hashtags on the trend list. These accounts contributed to the hashtag by 300-600 tweets per account[30] .

AFH Quantitative Findings on the Scale of MDM in Egypt

AFH is building the largest database of Arabic fact-checked posts covering the MENA region. The primary goal is to fill a crucial research gap in terms of having an accessible and updated database of high-quality fact-checked posts in Arabic. The value proposition of this database is:

Built by Fact Checkers

Unlike many published datasets, AFH does not scrape data and train people to further annotate it. Our database is populated and curated by fact checkers from various organizations who add domain-expertise and richer insights.

Serves Multiple Stakeholders

Currently published data mainly serves researchers who wish to build machine learning models. Ours target additional audiences like media and policy researchers.

Dialects and Multimedia

The database we will be building covers a wide array of data types and formats as well as dialects. Published datasets generally tend to cover modern standard Arabic content per se, and textual content. We will go beyond that.

Continuously Updated

Most published datasets are not maintained as they were used for the research that they were involved in. Our database will be continuously updated to always keep up with changes in the MDM ecosystem.

AFH is still in the process of populating this database, but for the purpose of this report, we decided to rely on the data we collected from our partner: Matsada2sh, a fact-checking organization that focuses on debunking wide-spread claims related to Egypt, mainly. We made the decision of merely analyzing Matsada2sh data because we obtained all their data with no gaps for the time period the report aims to cover, through an API integration with Matsada2sh site. We understand that this might make our findings skewed towards Egypt and from the point of view of Matsada2sh, but we tried our best to crosscheck the emerging trends and findings we detected with other MENA countries to reach better conclusions. Also, this report is the first publication in a series of reports that will continue to analyze more data with higher coverage and depth. Furthermore, Egypt has a unique and mature information ecosystem that witnessed various dynamics of information disorder, making it exemplary of what is actually (and could) happen in other MENA countries. Please note that the dataset used for this study can be shared with researchers upon request.

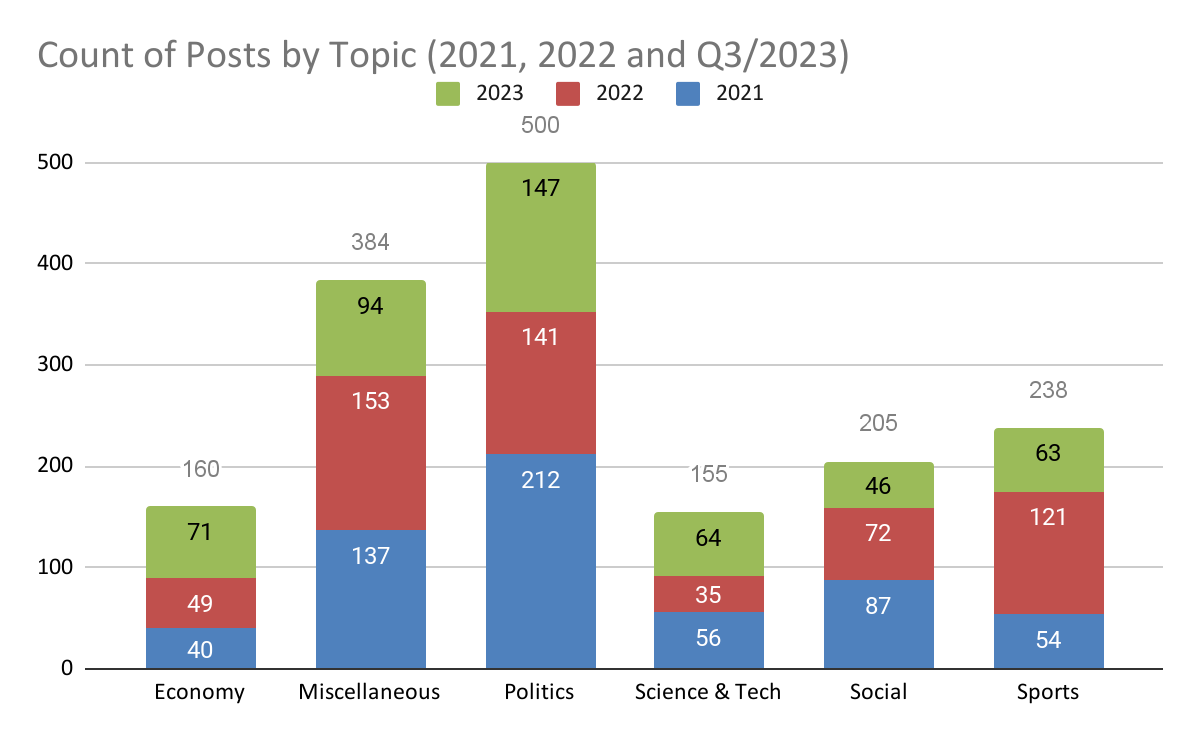

We analyzed 1,642 fact-checked posts that span 2021, 2022, and until the end of the third quarter (Q3) of 2023. The number of posts is shown below in Table 1. By the end of Q3 for the years 2021 until 2023, the year 2021 had 465 posts, the year 2022 had 427 posts, and the year 2023 had 485. This shows that although the data is until Q3 for 2023, the number of fact-checked posts in this year exceeded the previous years at the same quarter, which can indicate that the scale of MDM is on the rise. Note that Matsada2sh maintained a consistent fact-checking capacity across these years, hence, the increase is not attributed to any major increase in Matsada2sh operations.

|

YEAR |

Count of posts |

|

2021 |

586 |

|

2022 |

571 |

|

2023 |

485 |

|

Grand Total |

1,642 |

These posts are related to different topics as shown in Figure 1. The change in topics distribution over the years highlights major shifts in targeted topics, which can be attributed to many factors like the nature of events that took place in these periods, or the type of MDM tactics being used which could be more effective in certain topics. For example, the figure shows how in 2023 (Q1 to Q3) the topic “Economy” almost doubled in size compared to previous years. This is also true to a lesser extent for “Science & Tech”.

Figure 1: Count of Matsada2sh posts by topic

To understand the distribution over time, with more granularity as well as better comparability, Figure 2 shows the posts over time covering Q1, Q2, and Q3 only for the three years. The figure does not show any specific seasonality affecting the distribution, but it is noticeable that the year 2023 witnessed certain days where the number of posts increased substantially compared with the same time in previous years. One of the future research reports that we will work on is to overlay the actual events that took place in Egypt over this distribution to identify the correlation between the events and fact-checked posts. Moreover, to identify if the velocity of publishing MDM claims is getting lower over the years, which could be an indicator of how, unfortunately, efficient the MDM campaigns are becoming.

.png)

Figure 2: Count of posts covering Q1, Q2, and Q3 only for the three years

The brief analysis of Matsada2sh data definitely indicates an increase in volume and variety of MDM spreading in Egypt. Upon a closer look into the content itself of Matsada2sh posts, we found that traditional narratives under certain topics, for example how the previous presidential period of Mohamed Morsi is demonized, or how the LGBTQ community is targeted, still exist at a slightly increasing pace. However, we found a number of evolving and conflicting narratives under the same topic, like economic and monetary policies. What is unique about these narratives is they are loaded logical fallacies that likely aim to game the public opinion and to contrast a narrative against the other but not with the intention to raise the awareness, but to deceive and polarize the public.

Matsada2sh data showed a surge in fact-checked posts count including fake AI-generated images amid the global hype of ChatGPT, which started to pick up in April/May 2023 as shown in Figure 3. This was very clear, it was a trend that went viral globally and in the MENA. However, Matsada2sh data further shows that this trend of using fake AI-generated content was not sustainable and faded away, which suggests that the MDM ecosystem’s actors in MENA did not yet integrate the Generative AI in their MDM campaigns to a scalable level. This report will later discuss the potential challenges of generative AI on MDM in greater detail.

.png)

Figure 3: Google Trend analysis of interest over time in “ChatGPT” term[31]

We found that sports-related fact-checked posts represent the second highest share of posts in identified topics. Our analysis of Matsada2sh’s posts content led us to conclude that sport-related posts are the main vehicle used to gain higher reach and, consequently, financial gains. Rogue page admins and account owners abuse the popularity of sports in Egypt, especially football, to spread MDM and create trends. In certain instances, sport-related posts were used to push the political agenda of the government, like targeting specific football hashtags to publish MDM content aimed at rival countries.

As we moved towards 2023, we noticed a general increase in environment-related topics as part of the fact-checked posts in Matsada2sh. The main driver behind this increase is domestic as well as foreign due to the likely use of MDM campaigns by the Egyptian and Ethiopian governments targeting political and economic issues caused by the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam. The data shows that Egyptian audiences were targeted by these local and foreign MDM campaigns, where competing narratives were pushed. In other cases and at a much lower scale, specific environment-related MDM posts seemed to be pushed by organized groups of climate change deniers and flat earthers. Such content generally echoed global conspiracy theories and recycled viral content from somewhere around the world, with no noticeable innovation or localization.

The numbers reported in this section show a very grim situation. The scale of MDM is on the rise, getting more complex and effective. The role of generative AI, which will be discussed later in this report, is also rubbing salt into the wound. Is it a lost battle? How can someone beat advanced organizations like GlavNIVTs, Russia’s main Scientific Research Computing Center, which dedicates resources to crafting disinformation networks like Fabrika, with its operators claiming that only 1 percent of its fake accounts are detected by social media platforms?[32]

Illustrating the scale of MDM in MENA does not promote a cynical view, and by no means implies the lack of agency of authentic users. There are reports that showed how grassroots narratives prevailed over government-backed ones[33]. Moreover, the recent war on Gaza shows how collective efforts can be self-organized on Twitter, Facebook, TikTok, and others to counter massive disinformation well-funded MDM campaigns. The MDM applied to the recent war on Gaza can inspire a study on its own as a new era has emerged in terms of players, channels, tactics, scale, tools, and so on. This report was being finalized when the war started, so Gaza-related MDM is not covered extensively.

Who is behind MDM in MENA?

There are various actors who are involved in MDM campaigns in MENA. Some complex campaigns can involve multiple actors where prior coordination exists. In other cases, the dynamics of information diffusion on social media can attract additional, and sometimes unintended, actors to get involved. The nature of actors behind MDM in MENA is attributed to their access to power and resources, not only in the digital space, but the physical space too. Hence, these actors can be state and non-state actors as follows:

- Domestic and foreign governments and governmental organizations

- The private sector

- Social Media Platforms

- Nonprofits (domestic)

- iNGOs

- CSOs (parties, lobbies, pressure groups)

- The public (opposition and pro-regime)

This report will cover selected actor types who tend to have the major share in backing MDM campaigns in MENA.

Domestic and foreign governments and governmental organizations:

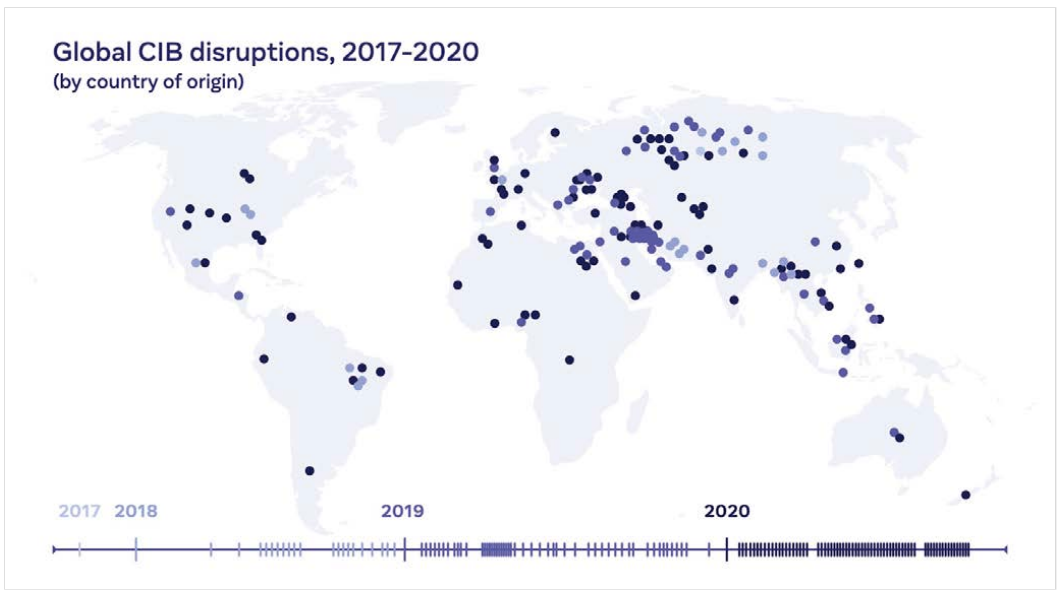

Facebook/Meta quarterly publishes reports on Influence Operations (IO) and Adversarial Threat reports to track campaigns with Coordinated Inauthentic Behavior (CIB) including their countries of origin. These reports generally confirm that IO are correlated with geopolitical events, and their scale and modus operandi is aligned with very powerful actors who most likely are affiliated to states. To put this in perspective, the threat report on the state of (IO) between 2017-2020 shows MENA as a very active place in terms of number of CIB campaigns originating from this area [35] as shown in the figure below. The CIB activity of these campaigns is sharply increasing towards being covert and advanced with time, as opposed to being overt, as reported in Facebook/Meta’s 2022 Q4 report when analyzing the Russian-origin IO campaigns related to Russia’s war in Ukraine[35].

Figure 4: Global CIB disruptions as reported by Facebook/Meta between 2017-2020

One of the early state-backed CIB IO that targeted MENA countries like Egypt, Yemen, and Sudan was discovered by Reuters in 2018 to have originated from Iran. The Iran-linked actors ran multiple campaigns through a network of 70 websites publishing content to 15 countries in Asia and Africa. A year later, the Citizen Lab uncovered an advanced IO operation led by Iran[36] targeting Saudi Arabia, USA, and Israel and was called “Endless Mayfly.”[37] The unique aspect of this IO is not just the use of a network of inauthentic websites and online personas, but the fact that all published content was systematically deleted after a period of time. Such an ephemeral approach allowed the content to last enough to serve the Iranian interests, but then disappear to cover any tracks. The network included 135 inauthentic articles, 72 domains, 11 personas, one fake organization, and a pro-Iran republishing network. Another Iran-linked network targeting MENA, beside other areas, was dismantled by the US Justice Department in 2020. The network included 92 web domains used in campaigns run by IRGC to spread disinformation while posing as independent media outlets[38].

Russia is an example of a foreign state actor that targeted MENA audiences with disinformation IO for a surprisingly long time. Dr. Nadia Oweidat, assistant professor at Kansas State University, explained how her research on disinformation in the Arab World led her to find evidence that Russia deployed systematic and consistent campaigns on digital mediums since 2010[39]. The evidence includes Russian bots or intelligence officers masquerading as “authentic Egyptian voices that are anti-colonial, anti-American, anti-Western.”

Within MENA itself, there are many documented IO of CIB originating from Arab countries targeting their people or other rivaling countries, following political, economic, cultural, or even sport-related conflicts. A key example comes from Saudi Arabia where an open source investigation by Bellingcat in 2019 identified a network of bots and tactics, including hacking, that were used to manipulate the public opinion of Saudi citizens and neighboring countries. The investigation led to a specific man called Saud Al-Qahtani who then had an official and powerful position in the Saudi government[40]. Such findings are likely the fruits of an institutionalized effort made by Saudi Arabia to build a disinformation apparatus, as uncovered by The New York Times in 2018. The disinformation apparatus recruits hundreds of individuals for an equivalent of $3,000 monthly salary to run the “troll farm” that targets dissidents[41].

Another CIB IO was attributed to Saudi Arabia state media in which hashtags discussing COVID-19 pandemic were used, or abused, to spread disinformation targeting the governments in Qatar, Iran, and Turkey[42]. Some went as far as blaming these governments for actively spreading the virus. Marc Owen Jones’s important book titled “Digital Authoritarianism in the Middle East” provides detailed accounts on many disinformation campaigns in the Arab world, especially those originating from Gulf countries[43].

Surprisingly, some MENA governments who actively practice disinformation and stand behind MDM operations were actually trained and equipped by “democratic” countries. For instance, it was reported that European Union Agency for Law Enforcement (CEPOL) provided extensive training in 2019 to Moroccan police forces in online disinformation tactics, which included creating “sock puppet” accounts, purchasing SIM cards for fake accounts, and using software to run multiple fake identities simultaneously[44]. Similar training was provided by CEPOL in April 2019 to the Algeria’s police force “National Gendarmerie” to apply digital surveillance and disinformation tactics like the using software to track the location of devices, use of sock puppets for open-source research, purchase different sim cards for different accounts, use picture editing tools, and to post frequently and outside of work hours[45]. Similarly, it was reported in 2023 that the forensic technology to counter cybercrimes that was donated by United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) to the Tunisian government was actually used to monitor online activities of political activists and arrest them on charges of conspiring against the state[46].

It took the state actors in MENA including domestic, foreign governments, and governmental organizations a few years to realize the power of social media and how technology penetrated the lives of Arab-speaking people in major MENA countries. When this was understood, the old tactic of divide and conquer quickly manifested in the form of state backed disinformation campaigns on Twitter and Facebook. Among the key goals of such campaigns was polarizing public opinion and manipulating hashtags that critique governments as a way to diffuse the public tension from accumulating to physical uprising[47]. MENA governments doubled down their disinformation strategy on social media and we witnessed how some organic hashtags and community-driven campaigns were hijacked and poisoned by state-controlled bots and troll armies. We even witnessed disinformation campaigns that were completely manufactured and amplified by troll and bots, creating what Marc Owen Jones calls a “pseudo–civil society.” [48]

Since their inception, social media campaigns have offered the MENA governments a cheaper medium to launch their campaigns; a way to automate campaigns with a huge volume of content to repeatedly expose the people to their narrative; a medium more trusted than traditional state-run media outlets; and an efficient space to reach multiple segments of audiences and measure the reach and effectiveness with data-driven insights.[49]

While domestic and foreign governments targeting MENA with disinformation campaigns generally use similar tactics, they differ in their strategies. Clint Watts, a senior fellow at the Foreign Policy Research Institute, describes Iranian disinformation campaigns to be strategic in design but “very hasty in execution”, unlike the more sophisticated campaigns backed by Russia that are carefully executed in alignment with their strategy[50]. Another difference in the Iranian and Russian campaigns is that the former tries to promote its own narrative and politics, whereas the latter tends to inflict polarization and deception in the countries it targets[51].

A key effort in understanding the scale of global disinformation and the countries it originates from was done by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI). The institute found that most of the state-linked disinformation on Twitter can be attributed to Russia, Iran, Saudi Arabia, China and Venezuela. In October 2019, Saudi Arabia based actors published 2.3 million tweets, a number that surpassed even China in that year by 20 folds[52]. The institute published insights on Russia-backed disinformation campaigns including those focused on Syria to discredit the White Helmets volunteer group. ASPI maintains worth-checking datasets and interactive dashboards on global disinformation[53].

That being said, MENA governments do not only act on the offense side of information disorder, but on the defense side, too. Knowing that MDM is a double-edged sword, many Arab countries have officially established dedicated authorities to counter information disorder with supportive legislation and laws. This side of the ecosystem was extensively studied in a pioneering research titled “Meeting the Challenges of Information Disorder in the Global South,”[54] which was led by Professor Herman Wasserman with contribution of four media organizations in the Global South: Research ICT Africa (RIA) covering Africa region, InternetLab covering Latin America, LIRNEasia covering Asia, and Arab Reporters for Investigative Journalism (ARIJ) covering the Middle East and North Africa. The research study surveyed and interviewed many actors in MENA countering the information disorder. But it shed light on how sensitive this topic is when it reported that a number of government agencies in Saudi Arabia and Egypt refused to cooperate or grant the research team interviews. Other organizations and individuals in Bahrain, Jordan, Egypt, and Tunisia refrained from completing the questionnaires. One key finding the study reported is that in many Arab countries where freedom of expression tends to be suppressed, the legislation criminalizing the publication of misleading information “has been used to suppress freedom of expression.”

Platforms:

The conundrum that social media platforms face as profit-seeking companies, while simultaneously accountable for maintaining global values like freedom of speech, can be very challenging. They could be successful when deploying features that promote such values, yet they could fail and get sued for their complicity with governments. An example is the allegation made against Twitter by lawyers representing Abdulrahman al-Sadhan who was one of thousands of Saudis whose confidential information was obtained by Saudi agents working at Twitter in 2014 and 2015.[55]

From a MENA perspective, it is controversial whether to consider major social media platforms to be part of the disinformation challenge, but the presence of their regional offices in countries like the UAE raises eyebrows. Afef Abrougui and Mohamad Najem, CEO of SMEX, a non-profit that advocates for and advances human rights in digital spaces across MENA, argue that technology for GCC governments is used as a “lever of power to control dissent and populations,” so they question the presence of big technology companies in GCC and highlight the intertwined relationship between politics and economy that could hinder digital rights in the Arab region[56]. This challenge is further exacerbated by the lack of dynamic regulations that protect the users, including data protection laws, privacy acts, cybercrime laws, and freedom of information.

On a deeper level, social media platforms constantly change their policies and algorithms, sometimes driven by financial gains, and at other times just following the views of their owners who do not necessarily put into consideration the whole situation. A major, and recent, example is X’s new owner, formerly Twitter, who was at the verge of potentially ending online anonymous activism and put the lives of Arab dissidents in danger when he suggested the “authenticating all humans” feature[57], which entails requiring anonymous users to disclose their true identities. Moreover, a DFRLab assessment found that around March 29, 2023, Twitter changed how its algorithms treat Russian, Chinese, and Iranian state media outlets[58]. NPR further confirmed such a finding and indicated that Twitter decided to stop filtering government accounts in these countries[59], and Reuters reported that the “government-funded” label was removed too[60]. These changes led the European Commission to conclude that Twitter under its new ownership heavily contributed in allowing Russian disinformation campaigns about Ukraine to achieve higher reach before the war began[61]. Moreover, lack of transparency of the new policy of allowing suspended accounts on Twitter to appeal suspension and achieve reinstatement, could open the door for malicious users to abuse it[62].

The changes made by the social media platforms do not generally consider the complicated context in various regions including MENA. This is especially apparent in how content related to uprisings and protests in MENA is usually disfavored by the algorithms[63], and other content is highly censored due to political reasons, like the pro-Palestine voices amid the current Israel’s war on Gaza[64]. On that note, the platforms’ political bias could overshadow their existing policies. This manifests in platforms' approach to mitigate compliance risk with powerful governments by submitting to their requests to remove opposing content. A staggering 94% of the flagged content by the Israeli state prosecutor’s office has been removed by Meta and TikTok according to the Israeli agency[65]. It is a legitimate concern to question how major platforms are siding with the aggressor in this war and whether they are cooperative in removing the disinformation content produced by that side or willful blindness is in play. Major platforms should be more transparent about their content moderation policies, as observing their decisions could make them look biased, or even incompetent as connotated by the experience reported by Marc Owen Jones when he informed Twitter about 1,800 accounts involved in spreading disinformation and hate speech in Bahraini hashtags, and how the accounts were only suspended due to their spam-like behavior[66].

The Public (Opposition and Pro-Regime):

The scale of disinformation practiced by state-actors in MENA led some opposition groups, whether political, economic, environmental, or social groups to adopt disinformation tactics to fight back. Although such tactics are similar, this by no means equates the scale of operations between the state and non-state actors, as the former has access to more resources, and tends to be centralized, whereas the latter is more decentralized.

One of the key opposition groups that orchestrated disinformation campaigns in MENA and was thoroughly analyzed is the Muslim Brotherhood (MB). Stanford Internet Observatory, which analyzed many state-backed disinformation campaigns in MENA, closely studied a MB-Linked network that was taken down by Facebook in November 2020[67]. The analysis covered 25 pages, 31 profiles, and 2 Instagram accounts which originated in Egypt, Turkey, and Morocco and targeted Egyptian audiences directly and other MENA countries indirectly. The network was cross-platform with access to YouTube and Telegram channels that have a large followers base. They published disinformation content criticizing Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and UAE while praising Turkey and Qatar.

According to another report, the disinformation campaigns led by MB-linked networks can still target MENA audiences but for an overseas cause. The India-based “The Disinfo Lab” uncovered online disinformation campaigns launched in September 2020, which called for boycotting India for its role in Kashmir conflict, originated from troll factories linked to MB groups in Turkey and Pakistan. The report mapped various NGOs, companies, and alleged fronts that help MB in their media disinformation campaigns[68]. Note that we were not able to verify the credibility of this report, nor the independence of “The Disinfo Lab” from the Indian state, so we clearly ask readers to view this report and the reported networks distrustfully.

The general public in MENA is more decentralized than opposition groups but can form spontaneous and short-term networks that can actively contribute to the disinformation discourse. As any audience, the public can be polarized where some segments become pro-government, while others are against. For more information on the disinformation tactics that can be practiced by the public, researchers from Harvard University and University of Toronto published a study on the three I’s: inauthenticity (use of automation and fabrication tools), inequality (reliance on the impact of influencers), and insecurity (use of intimidation and repression) explaining the key tactics and how they differ from a centralized, i.e. state, entity[69].

Private Companies:

Private companies play a vital role in advancing the disinformation campaigns in MENA. Propaganda-as-a-service is not new, but with the rise of social media, many players entered into this space including traditional PR firms, based in MENA and around the world. The previous section of this report highlighted the scale of MDM operations in MENA, which gives an idea on the size of this industry and spendings. Probably one of the many dark sides of this industry is the lack of accountability of owners and workers who operate such companies. This report will later discuss how online MDM can cause physical harm, but stories like Cambridge Analytica on how online manipulation transcended into undermining democracy[70], and although the firm was dissolved, its executive moved freely to another firm. A detailed investigation report by Wendy Siegelman uncovered that “Project Associates” contracted with “SCL Social Limited” (in September 2017), whose director was Alexander Nix, former CEO of Cambridge Analytica, for $330,000 to launch campaigns on Facebook against Qatar[71]. This lack of accountability and simply playing by the free market rules cannot stop the proliferation of the disinformation economy.

There are two main scenarios on how the private disinformation industry operates in MENA. The first scenario is when a predator country contracts with a foreign company to target Arab-speaking audiences with disinformation. The predator country could be foreign. This is the story of the UK-registered media firm called “Yala News”, which was exposed by the BBC's Disinformation Team to be spreading and mirroring Russian state disinformation targeting MENA audiences[72]. Another variation is when the predator country is within MENA. An example is the team of Israeli contractors who developed and used a bot-management solution called Advanced Impact Media Solutions, or Aims, and offered it through an Israeli company called Demoman International. The software controls thousands of fake profiles on Twitter, LinkedIn, Facebook, Telegram, and other mediums. The Guardian uncovered the operations of this team, and interviewed Tal Hanan, a 50-year-old former Israeli special forces operative, who claims to have manipulated more than 30 elections around the world using hacking and automated disinformation on social media. The Guardian and its reporting partners tracked Aims-linked bot activity across the internet and found that it was behind fake social media campaigns including the United Arab Emirates[73].

The other scenario is when a predator country contracts with a domestic company to target Arab-speaking audiences with disinformation. In 2019, Facebook disabled a network of accounts linked to Egypt and UAE-based firms. The companies were “New Waves” in Egypt and “Newave” in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), which targeted MENA audiences across Egypt, the UAE, and neighboring countries with influence operation campaigns[74]. Other examples of such companies are Elite Media Group in Saudi Arabia, whose activities were detailed by Marc Owen Jone[75]s, and the Union Group in Egypt that has indirect control over disinformation campaigns in Egypt[76].

AFH Research Findings on the Actors of MDM in MENA

Our analyses of Jordan, Lebanon, Yemen, and Egypt by the AFH’s OSINT team has helped us uncover many interesting facts and trends regarding the possible actors behind the MDM campaigns in the MENA.

In Jordan, misinformation campaigns showed how the lack of reasonable regulations on MDM that considers the end-users’ point of view can be ineffective in meeting its very objectives. It can also lead to accusing regulators for politicizing the regulations to limit freedom of expression. Furthermore, the lack of regulatory vision and transparency immediately lost a key stakeholder in the ecosystem: the general public. This dynamic has most likely fueled the incident we studied and caused a reactive action from influential actors upon the leak of private pictures of the crown prince and his new bride, hence leading to orchestrated MDM campaigns. In addition, this might have sent the wrong message that a regulation was truly applied when powerful people in society were affected. It was promoted and lobbied for by the state media pro-government influencers. It is believed that the unwise management of this situation backfired and caused more users to search for the leaked images, which is a classical story in MENA countries: forbidden fruit is the sweetest.

The analysis further showed that some influencers played a misleading role in these campaigns, which reinforced the top-down MDM. Such influencers did not call for certain community values that could help fight disinformation and promote regulations that are in tandem with freedom of expression. Instead, they shared arguments implicitly favoring the elite groups in power, mixed their discourse with conservative tribal customs, calling for going back to society’s roots, so they became, intentionally or unintentionally, part of advancing the disinformation campaigns around the cybercrime law in Jordan. This is “astroturfing” tactic at best and will be further discussed later in this report.

Moving to Lebanon, our analysis on the actors behind the MDM campaign that targeted the LGBTQ community shows that it started with influential figures in Lebanon who have a conservative anti-liberal mindset across different religions, but quickly spread beyond borders, reaching countries like Yemen, Egypt, and the Gulf. Polarized masses with ideological worldviews who are being exposed to identity politics discussions in the West were ready for mobilization in this campaign. This quickly led the MDM campaign in Lebanon targeting LGBTQ community to become a regional trend with involvement of more actors. In the near future, we will develop a research report trying to answer important questions in these campaigns like: what are the MDM campaign dynamics that cause these hashtags to go viral? What are the social, political, economic, and cultural drivers affecting that? Do these hashtags grow organically then they are hijacked or orchestrated by organized groups? Or the opposite? Is it a hybrid of both? Did some influential state and non-state actors contribute to these campaigns in a self-managed or disorganized way, yet it converged to organized coordination overtime? Are there organized groups across MENA that join forces on specific topics?

The story analysis further showed how nuanced and different the discourses are, even those belonging to the same MDM campaign, which corresponds with the unique local context of each country or society. Furthermore, these nuances magnify the different social structures, governance models, and rule of law across MENA countries. Some MDM campaigns liberally called for violent physical actions while some stayed with bullying and harassment on the digital spaces. Also, we found that conservative actors, mainly influencers and political/religious figures, participate in campaigns on these topics to advance existing discourse but in a modernized way that speaks to young generations. It is like piggybacking active discussions to spread certain ideas. This further involves recycling extremists’ “Western” rhetoric and repackaging it for Arabic audiences to give it some legitimacy – that even the West, the propagator of these ideas is suffering. This is usually a slippery slope for spreading MDM, intentionally or unintentionally, because it is often mixed with emotionally charged arguments where logical fallacies are commonly used. In certain topics, as we saw in the LGBTQ MDM campaign in Lebanon, demonizing marginal groups was part of it.

These research findings led us to ask questions that we will focus on in our upcoming studies. For example, what can MDM campaigns tell us about the real biases and imbalances that exist in our physical and digital ecosystems? How does violence cascade in MENA societies and cause cycles of abuse to trickle down? These are very serious questions in MENA countries because the lack of sufficient state action (rule of law and regulations) and lack of evolving societal protocols/practices does not only prevent MDM campaigns from targeting marginalized groups, but it extends to punishing any sympathizers with them. It helps manifest everything wrong in society.

When we analyzed the story that our OSINT team uncovered on Egypt, it was clear that actors in some countries have higher maturity in terms of organizing MDM campaigns than others. It is not related to having access to more technical resources per se, but it includes deeply understanding the behavior of the targeted audiences. This plays a role in making specific MDM campaigns more pervasive than other campaigns, especially within specific topics like gender-based violence. The story of Nayera Ashraf in Egypt showed how certain narratives prevail and how the public focus can be shifted from blaming the perpetrator into blaming the victim. It was noticeable seeing a unique set of actors who claimed to be relatives of the victim and then in a very deceptive and subtle way, tried to exonerate the perpetrator. This is a double-fold challenge for truth-seekers and fact-checkers, as debunking needs to consider the identity of the actor as well as the narrative it publishes. What is more challenging, and is one of the trends that we identified in the MENA’s information disorder ecosystem, is the wide-ranging use of hard to fact-check content like live streams, especially those coming from someone claiming to be close to the victim, or just asking intentionally intrusive questions to distract the audience.

In Egypt, like in Gulf countries, it was very clear how many pages/accounts systematically participated in trending topics to gain more reach, visibility, and eventually financial gains. Such participation did not necessarily include publishing or amplifying MDM content, but the modus operandi of these pages, accounts, and the private-sector companies behind them highlight how they strive to maximize their reach and gains. This begs a crucial question about the business models that drive MDM campaigns into these vicious cycles to gain more reach and financial proceeds. One of the future research objectives of AFH is to study the media business models in MENA that drive MDM campaigns. One starting point is to extend the fascinating “actor mapping” work done by Global Media Registry and its partners in what they called: “Media Ownership Monitor.”[77] which includes MENA countries like Egypt, Lebanon, Morocco, and Tunisia. One of the key findings reported by this project is that the media in MENA is generally owned by small elites who are close to governing regimes. Some unique characteristics distinguish these countries, like how the media monopoly in Lebanon is driven by specific families directly linked to political parties and religious chiefs, and how specific private-sector companies in Egypt own major media outlets and act as merely fronts to the security apparatus or the Egyptian army.

One recurring dynamic that we discovered in Egypt, again like in Gulf countries, was the weaponization of MDM campaigns by political actors to score points against regional rivalries. What we saw is very similar to the examples mentioned in the literature survey of this section, where both regimes and their opposition are involved in initiating MDM campaigns, although at different scales. The involvement strategy of specific MENA countries in the MDM campaigns is very overt, where they have invested in state resources and private sector companies to conduct the campaigns, whereas other countries are likely using covert strategies to push MDM campaigns through informal media arms, opposition (of the targeted country) living in exile, and public relation firms.

The MDM ecosystem in MENA can be very hostile, leaving physical implications on societies. It is very unfortunate to witness how various actors recklessly launch MDM campaigns during political conflicts that drag the public into severe battles. But when governments find a compromise, people are just asked to celebrate and rarely does someone care about the damage and rift caused as a consequence. This is probably telling on how the public is looked at and considered in this information disorder ecosystem. When some watchdog groups try to hold these governments accountable, they are either intimated, arrested, simply ignored, or in some MENA countries, governments would use the law to avoid giving information or be transparent.

Another unfortunate reality is to see some opposition groups acquiring similar traits of their oppressors and gradually becoming a replica of what they originally opposed. Finally, this unregulated landscape opens the doors wide open to entrepreneurs who wish to utilize the attention economy for their gains and interests, as well as media platform owners who change their policies with little regard to how such changes could enable more MDM campaigns.

AFH Quantitative Findings on the Actors of MDM in Egypt

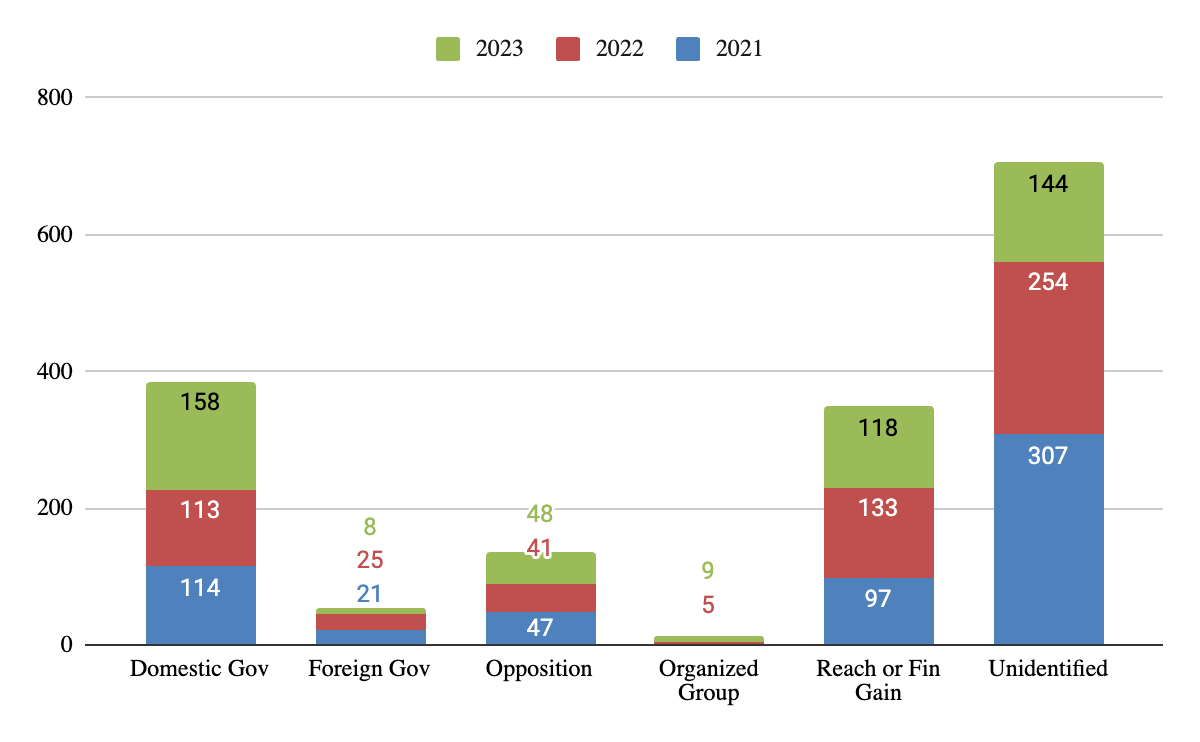

We continued our analysis of Matsada2sh fact-checked posts, spanning 2021, 2022, until the end of the third quarter (Q3) of 2023, but we introduced a new variable called “Plausible/Possible Actor.” This variable aims to identify the probable beneficiary behind launching each of the 1,642 identified MDM campaigns and verified claims by Matsada2sh. As part of their verification process, Matsada2sh focuses on the content itself, whether textual, image, or video, but they also identify, when possible, who took the main role in initiating the claim. This helped us construct this variable by associating the claim initiator to domestic governments, the opposition, organized groups, foreign governments, pages seeking popularity and reach, or simply unidentified. Furthermore, we created a sample of these claims and corroborated them with publicly available sources that fact-checked them and directly linked them to actual actors.

Please note that this variable identifies probable associations and does not provide a decisive adjudication. Hence, we used this constructed variable as an indicator, and the association identification methodology will be enhanced in future research. As a result, and given the nature of the data, and despite our best efforts to cross-check the information, we cannot guarantee the accuracy of all details. We ask anyone interested in this topic to contact us with revision suggestions.

Our analysis shows that the state of Egypt, denoted as “Domestic Gov” in Figure 5 below, is possibly the main actor behind the majority of MDM campaigns in Egypt, especially under the topics of politics and economy. We noticed a 39% increase in the volume of these campaigns until the end of Q3 of 2023, compared to previous years. This number is most likely increasing as we reach the end of Q4. These campaigns are usually amplified by influencers and mouthpieces. This provides a possible indication that state-backed MDM campaigns are on the rise in Egypt.

Figure 5: Matsada2sh fact-checked posts linked to possible actors over the years 2021, 2022, 2023 (Q3)

In addition, we noticed that besides focusing on politics and economy, the government is using societal issues as well as regional conflicts to advance its agenda and score political points against its rivals.

Foreign countries' involvement in MDM campaigns targeting Egypt seem to have reduced in 2023 compared to previous years. This is probably due to the decrease in discussions around the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) as well as some key political rapprochement and reconciliations that took place in MENA in 2023.

Pages and accounts that seek to maximize reach and financial gains mainly used sport-related topics amplify or publish MDM content. Our analysis showed that they are the second largest actor in Egypt. However, their involvement seemed to have declined in 2023 compared to previous years, this is possibly due to restrictions enforced by platform owners on sponsored content and tactics that game or manipulate or trick the content ranking algorithms.

On the sport-related MDM campaign, we noticed government’s involvement in specific campaigns that aimed to conduct “sportswashing”, which is using sports to improve or enhance reputations damaged by previous wrongdoing[78]. This is becoming a trend in other MENA countries, like in Gulf countries, but on a global scale[79].

Posts associated with the opposition maintained its volume over the years, but this could slightly increase in Q4 of 2023 especially during the presidential elections in Egypt, which is taking place in December 2023. Most of the opposition’s MDM campaigns that Matsada2sh identified were initiated by opposition TV anchors or YouTube influencers living in exile.

The last actor type we analyzed was the organized groups, which are more active in technology and science topics, where their content mainly focuses on conspiracy theories. Another organized groups that seem to be rising in Egypt and getting more involved in MDM campaigns are the Kemetism[80] and Afrocentrism[81] supporters.

One of the future research topics that AFH will cover is to conduct a comparative analysis between MENA countries on topic-specific MDM campaigns. For example, while analyzing Matsada2sh data, we did not notice in Egypt any pattern of environment-related disinformation campaigns backed by private companies. This is unlike the situation in Iraq where private companies actively get involved in such campaigns to hide their wrongdoings on the environment.

To conclude our analysis, we tried to categorize the drivers behind government-backed MDM campaigns in Egypt and noticed that they usually fall within the following:

- Testing the waters and assess public response before announcing major policies or regulations

- Part of any crisis management, in which the state is majorly accountable

- Inner conflict or skirmishes within the government agencies themselves

- Targeting regional rivals and domestic opposition or those in exile

- Reinforce polarization and public manipulation following a divide and conquer strategy

What are the drivers behind MDM in MENA?

On the 13th of August 2023, a private plane landed in Lusaka, the capital of Zambia's international airport boarding from Cairo, the capital of Egypt. What seemed to be a regular business trip unfolded to a rather extremely bizarre scandal involving $5m in cash, fake gold, guns, ammunition, and corrupt individuals linked to the Egyptian authorities[82]. AFH's partner, Matsda2sh[83], played a courageous role in investigating the story and uncovering major details, highlighting the wrongdoings conducted by influential elites in the government. When the government realized its initial response of bluntly denying all the evidence published by Matsda2sh, it mobilized its digital arsenal and implemented various misinformation tactics to absorb the heat of public opinion. This included publishing half-truths, discrediting Matsda2sh, mass reporting its Facebook page, publishing counter hashtags, and demonizing it and its funders. A few days later, harassment and threats transcended the digital space and manifested in arresting Karim Asaad, a member of Matsda2sh editorial team, which caused a global uproar that eventually led to releasing him and admitting certain details by the government regarding the private plane scandal.

This recent story highlights some of the key drivers behind the use of MDM, like advancing financial interests, political gains, and cultural hegemony, as well as perpetuating dictatorship and the status quo of lack of transparency and accountability. As highlighted in previous sections of this study, the MDM actors are of different nature, state and non-state actors, but the state actors remain the most resourceful and the most vicious in restricting the freedom of speech, conducting mass surveillance, and manipulating the public opinion. This is not limited to countries known for restricting press and publications, as measured by Reporters Without Borders’ Press Freedom Index[84] and The Economist Democracy Index[85] (note how MENA countries are ranked among the lowest in 2023). This extends to democratic countries where political polarization and competing for influence led some state actors to be involved in MDM activities. One of the consequences of such a challenge in Europe led the EU to create a European Democracy Action Plan in 2020 that called for protecting the integrity of elections and democratic process from disinformation applied in online campaigning[86].

The World Economic Forum declared in its 2023 Global Risk Report [87]that MDM is a short- and long-term global risk, categorized under "societal" risk. Furthermore, the report considered the MDM risk to be directly interconnected with "erosion of social cohesion" and "cyber insecurity"[88] risks as well as a major driver in the "interstate conflict" risk[89]. Unfortunately, the political and economic gains facilitated by MDM is hindering serious efforts required by resourceful actors, like states, and was clearly highlighted in WEF's 2023 report when it considered the perceptions around preparedness and governance to counter this risk by local governments, businesses, and other stakeholders to range between "highly ineffective" and "ineffective."[90]

Drivers of MDM, like the political interests, evolve as the geopolitics landscape changes. This leads to continuous evolvement of the MDM tactics as well as an increase in the operating model's maturity of the state actors. One manifestation of such a maturity dynamic can be seen in establishing dedicated entities mandated to handle such operations. Reporters Without Borders (also known as RSF) tracked such dedicated actors and published in 2020 a list of what it called: press freedom’s digital predators[91]. Digital predators are companies and government agencies that leverage technology to harass journalists; apply mass censorship; run disinformation campaigns; and spy on journalists and activists to jeopardize people's ability to access authentic news and information.

Some of the MENA digital predators according to RSF's 2020 list are:

- Harassment: