Archiving the Gaza Genocide on Instagram

Since October 7, 2023, brave Palestinian journalists and content creators based in the Gaza Strip have risked and sometimes lost their lives to publish videos, images, and text commentary of the genocide to social media. As a result, social media has become a de facto archive of the genocide, of potentially great value to war crimes litigators, scholars, civil society, and posterity.

Unfortunately, the role of genocide librarian sits awkwardly with the social media platforms, which treat this content with indifference or even hostility. As a consequence, all of that content is in danger of being lost as the accounts of Gaza content creators are suspended, hacked, or deleted.

Across the globe, concerned citizens, scholars, journalists, and civil society organizations, have been working independently to archive this social media content before it is lost. In this report, we investigate some of the challenges faced by this community, and take a close look at one effort in particular focused on archiving Instagram content. Our findings highlight both the enduring value of social media as a means of circumventing restrictions imposed on traditional news media; and the challenges of preserving and indexing such content in the face of corporate indifference.

Bearing Witness to the Apocalypse

After the events of October 7, 2023, the Israeli army unleashed a withering assault on the Gaza Strip that has continued to the time of writing (April2025). In that time, it is believed that over a hundred thousand Palestinians in Gaza have been killed, and as many or more have been injured. Nearly the entire population has been internally displaced. Most buildings, including all hospitals, and many schools and places of worship, have been obliterated.

Gaza-based Palestinian journalist Hind Khoudary photographed in September, 2024, during an interview with Slow Factory / Everything is Political. Restrictions on international news outlets accessing Gaza exacerbates a broader trend in which audiences shift attention from traditional news media to social media content creators. https://www.instagram.com/p/DBhXPpbS6fZ/?hl=en&img_index=1

Throughout this time, the state of Israel has forbidden international news media from sending reporters to Gaza except where chaperoned by the Israeli army itself. For unfiltered coverage, the world has relied upon a handful of news outlets such as Al-Jazeera, which had equipment and crews already based on the ground in Gaza prior to 10/7; and on ordinary Palestinian residents of Gaza who have taken it upon themselves to film, photograph, and narrate the violence and hardship. Thanks to the collective efforts of professional journalists such as Wael Al-Dahdouh, Ismali Al-Ghoul (killed in summer 2024), Hossam Shabat (killed in Spring 2025), and social media content creators such as Hind Khoudary or Bisan Owdeh, the Gaza genocide has been documented firsthand.

The Ephemerality of Social Media Content

But what happens to all of this social media content after it is uploaded? The profit motive of social media companies like ByteDance (TikTok), Meta (Instagram, Facebook), Google (YouTube), or Twitter (Twitter/X), is to keep users engaged with a never-ending stream of new material. They do not see themselves as librarians. Content older than a few hours, let alone a few days, is passe. It may continue to exist in the annals of the platform, but one is unlikely to encounter it after it has lost its initial novelty.

Social media companies are also not configured to preserve content for the sake of collective memory. According to their business model, original uploaded content is the property of the content creator, and it is their prerogative to delete or hide it – even, for example, if it amounts to evidence of war crimes.

Relatedly, social media companies are also not particularly committed to the security of any subset of their users, over and above the rest. A journalist under fire in Gaza receives no more support for securing or backing up their account than, say, a fashion influencer in Milan. If the journalist’s account is hacked and content is lost, this is viewed through a corporate lens, as an individual customer’s misfortune. That it might represent something wider, such as an obstruction of justice (if the lost content pertained to war crimes), or even a cultural loss or tear in the fabric of a shared history, is never considered.

Likewise, if a content creator on the ground in Gaza decides to geo-tag their location when uploading content, social media companies do not take it upon themselves to warn them of the implications. It emerged in early 2024 that the Israeli army was using an artificial intelligence system known as Lavender to pick targets inside Gaza, and that digital trace data (including social media activity) was an important input to this system. There is every reason to believe that the self-reported geolocations of Gaza social media users may have factored into the AI’s calculations when evaluating potential targets. Nonetheless, users were not warned or prompted to reconsider their decisions. Between October 7, 2023, and March 15, 2025, we calculate fully 16.1% of Instagram posts published by Gaza content creators were geo-tagged.

Finally, social media companies do not take it upon themselves to tailor their content moderation rules to accommodate the documentation of a genocide. In the Instagram data collection described below, 4.2% of content was automatically flagged by Meta’s algorithm as graphic or sensitive, whereupon its visibility across the platform was restricted. While in general it may make sense to limit the visibility of upsetting content, depriving international audiences of a full-resolution picture of an ongoing genocide potentially dampens the kind of backlash that might otherwise bring a swifter end to the violence.

For all of these reasons, social media companies cannot be relied upon to preserve or index content pertaining to a defining event like the Gaza genocide.

Civil Society Archivists

To fill the void left by social media companies, civil society organizations and concerned citizens across the world have been making sincere efforts to archive social media content pertaining to genocide. For example, the Accountability Archive provides a platform to receive crowd-sourced data on journalists, politicians, or other public figures, who after 10/7 applauded and encouraged the genocide or ethnic cleansing of Gaza. TikTok Genocide is an effort to archive videos uploaded to TikTok – often by Israeli soldiers deployed in Gaza – showing evidence of potential war crimes. In addition to saving the videos, the team behind the site also tags videos with contextual information to link them to specific locations or events, thus facilitating their usefulness for war crimes litigation.

To understand better the technical and personal challenges of this work, let us look more closely at one such archiving project known as SaltPillar.

SaltPillar

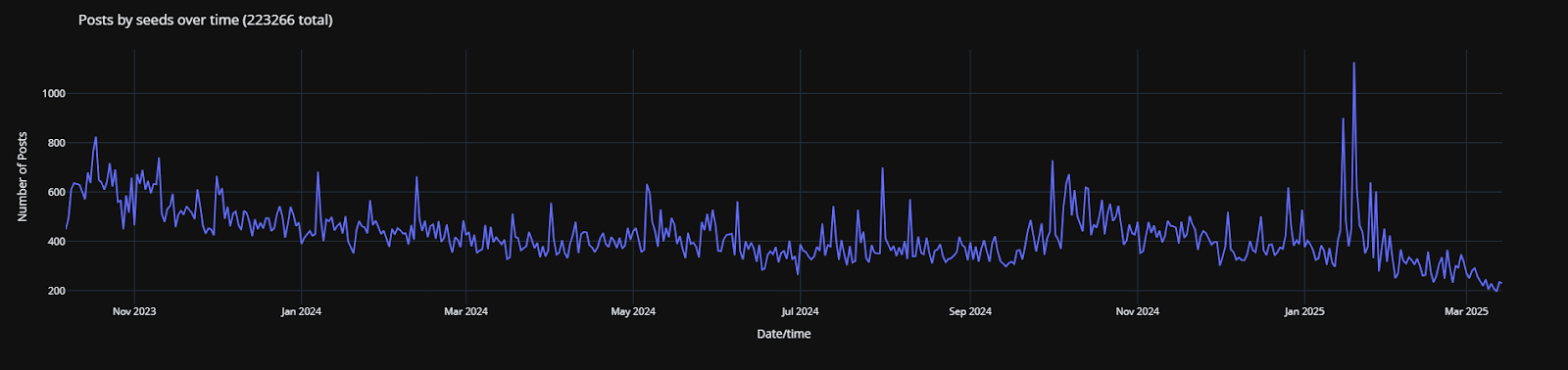

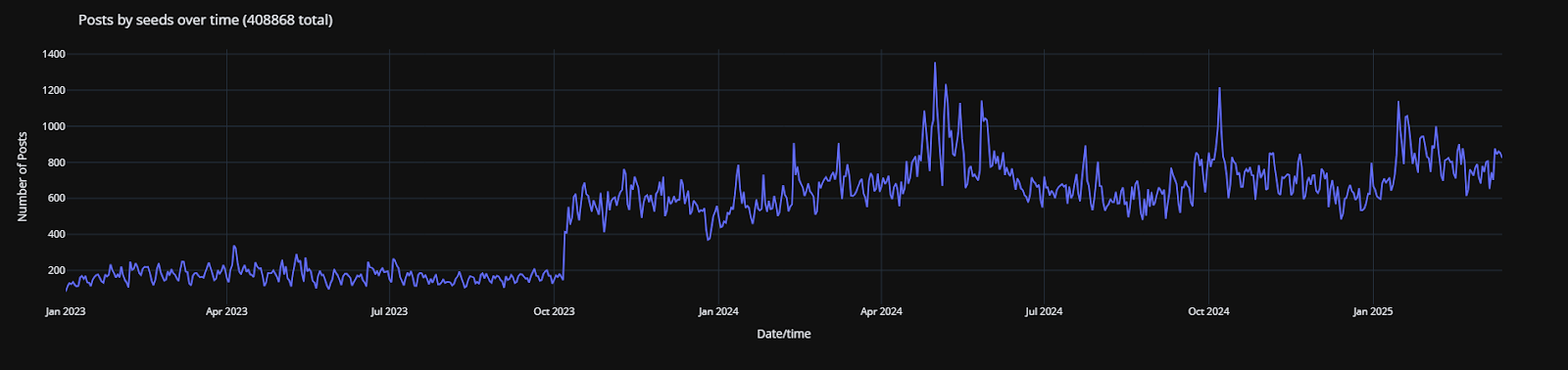

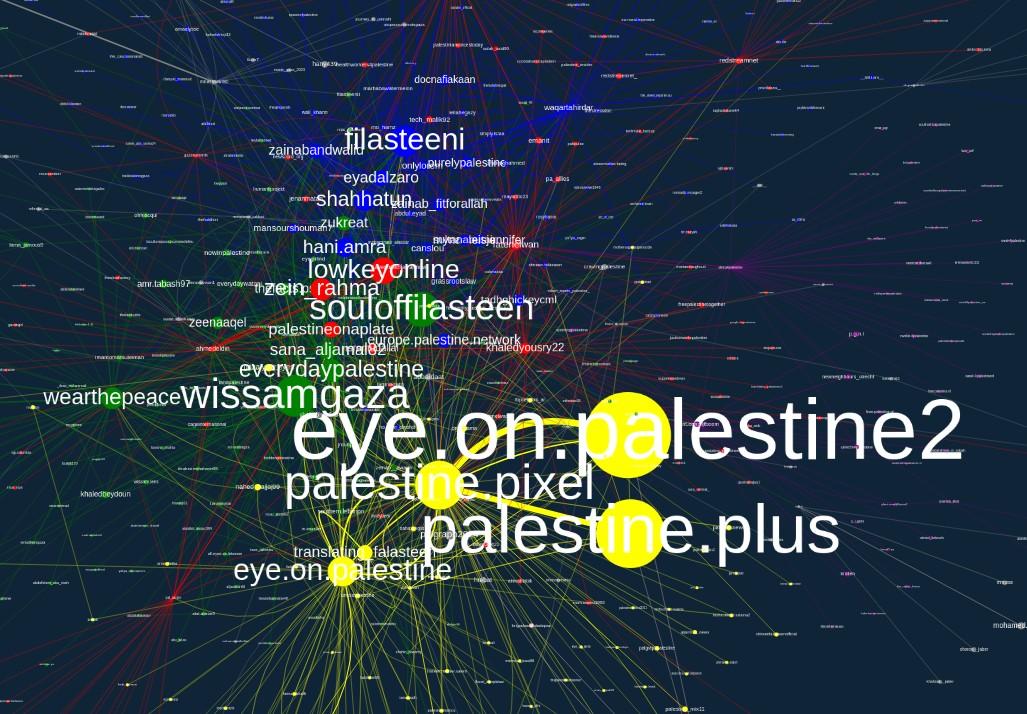

SaltPillar is a Tech For Palestine project focused on archiving Instagram content pertaining to the Gaza genocide. First and foremost this means archiving images, videos, text, and metadata of content creators (320+ as of the time of writing) posting from ground zero in Gaza, from October 7, 2023, to present. But SaltPillar also tracks pro-Palestine protest activity around the world (930+ organizations).

Time series showing the number of Instagram posts or reels published daily by Gaza content creators, from October 7, 2023 to March 15, 2025. Source: SaltPillar.

Time series showing the number of Instagram posts or reels published daily by pro-Palestine protest organizations around the world, from January 1, 2023 to March 15, 2025. Source: SaltPillar.

Network map showing Instagram coauthorships between Gaza content creators and others inside and outside of Gaza. Source: SaltPillar.

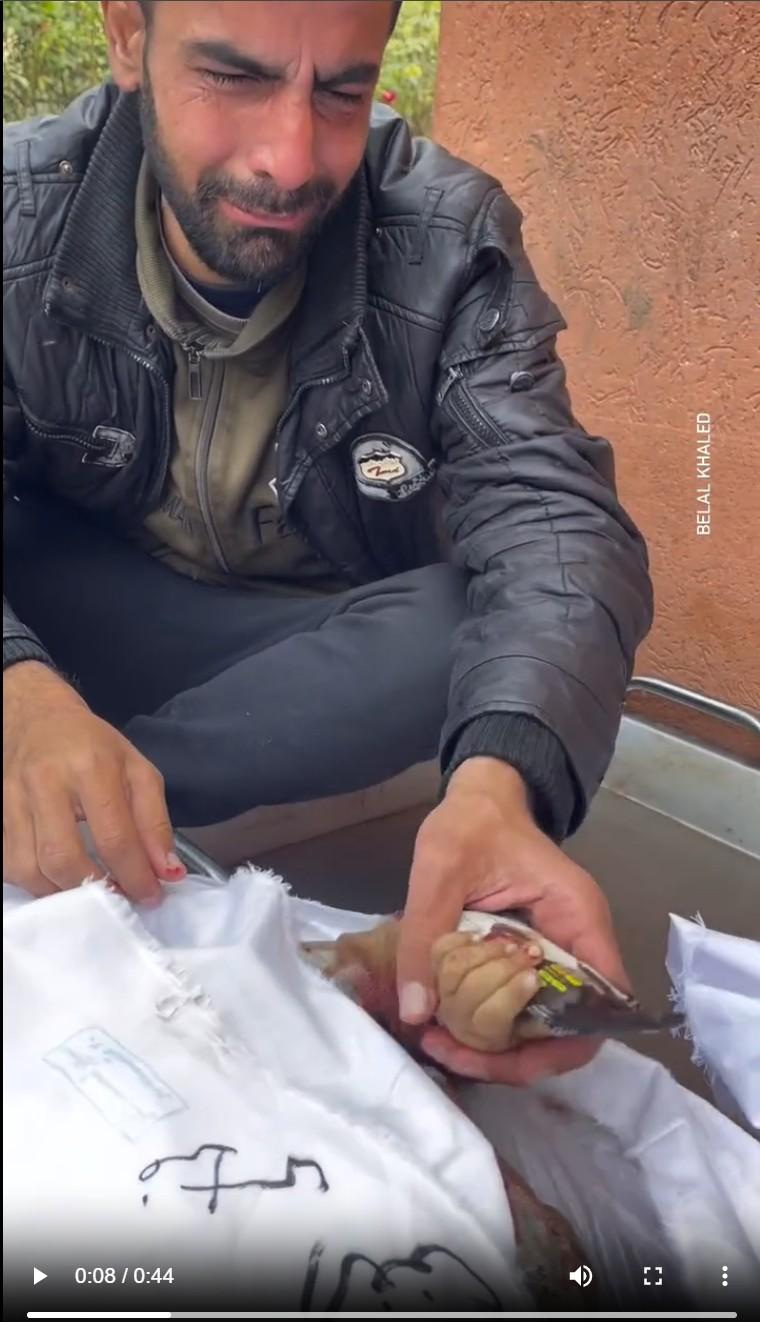

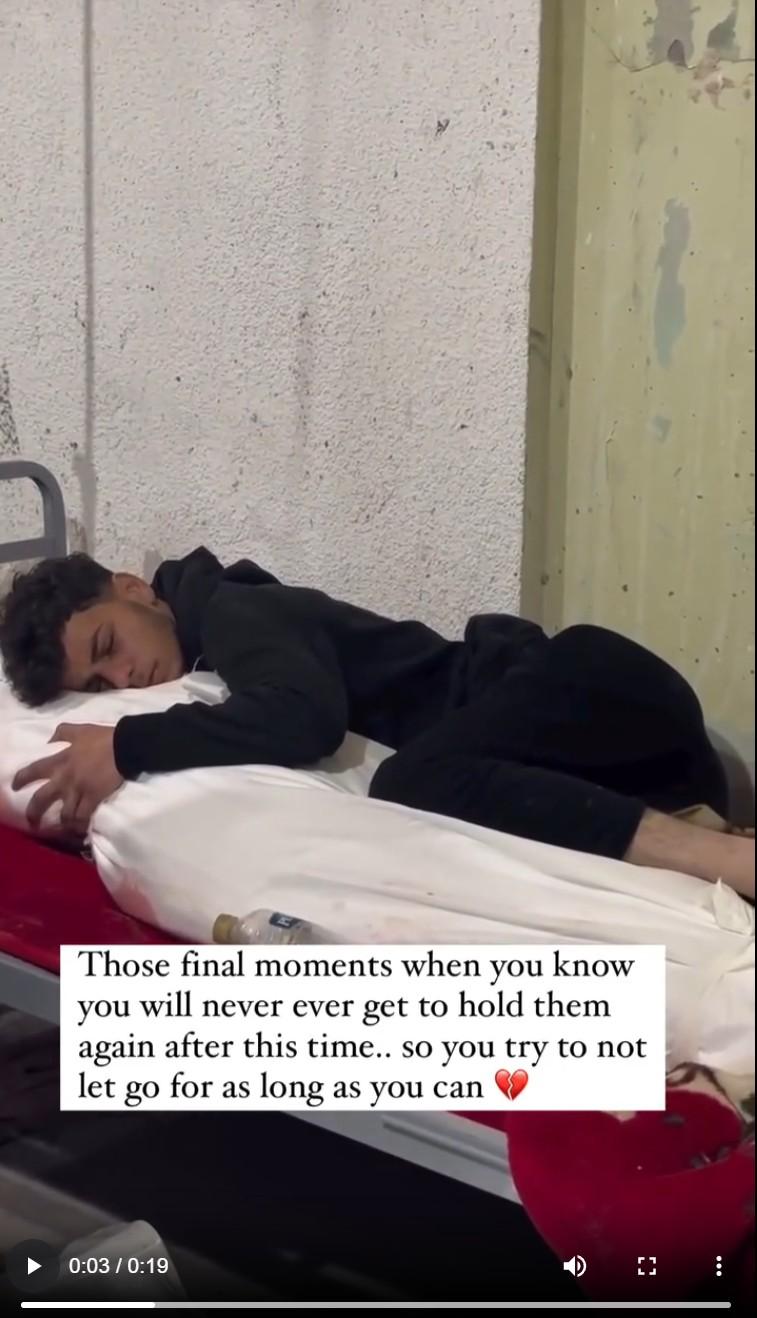

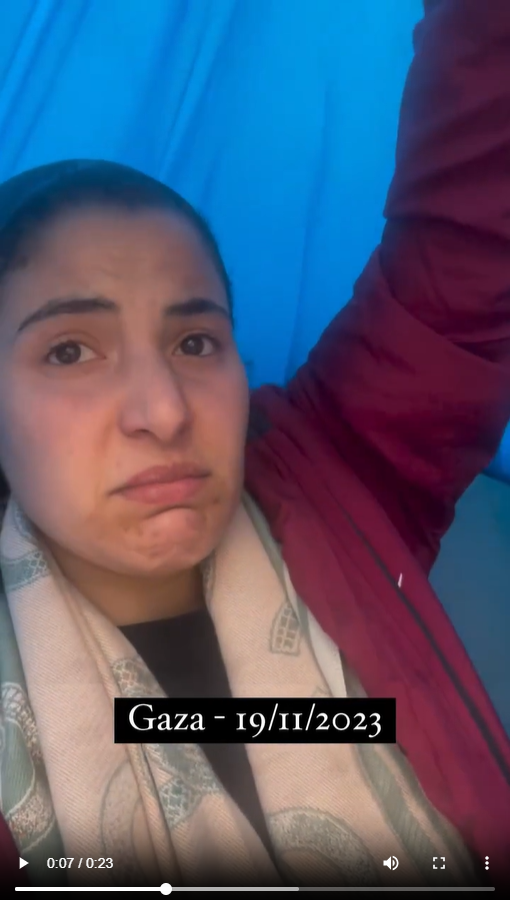

Videos published to Instagram of Palestinians in Gaza experiencing hardships of hunger and internal displacement.

@eye.on.palestine December 18, 2023 https://www.instagram.com/reel/C0-5MKKq8t9.

@motaz_azaiza November 10, 2023 https://www.instagram.com/reel/Czd2z_ZMjWz.

@motasem.mortaja October 18, 2023 https://www.instagram.com/reel/CyimYI8rCdl

@belalkh https://www.instagram.com/reel/C1ZVhA1s_il

@wissamgaza https://www.instagram.com/reel/C3Oz8gZukEM

Left: Motaz Azaiza stands amid the destruction of a Gaza City neighborhood. Bottom left: “It’s raining!”

Right: Bisan Odeh, in tears, conveys the horror of the internally displaced living out of tents as winter arrives in Gaza. Source: SaltPillar.

Videos uploaded from Gaza to Instagram showing hope or resilience.

@doaaj94 November 23, 2023 https://www.instagram.com/reel/Cz_2e6CrpIS

@i.anasmatar January 13, 2024 https://www.instagram.com/reel/C2C6L1fo_EG

Adversarial data collection

The indifference and occasional hostility that social media companies exhibit towards the archiving of genocide-related content is not unique to Palestine or genocide. In recent years, social media companies have steadily rescinded data access to journalists, scholars, and civil society organizations, and have adopted an increasingly adversarial relationship with the public interest research community. After Elon Musk took over Twitter/X in 2023, he ended free-tier and academic-tier API access, upending research focused on detecting and mitigating online harms. Reddit soon followed suit, and in August of 2024, Meta sunsetted CrowdTangle, its last remaining public interest research tool for Facebook and Instagram. TikTok never offered API access to begin with, and its application process for obtaining access is formidable, and moreover restricted to Western research institutions. Of the major platforms, only Telegram continues to offer substantial API access for free.

To make headway, civil society actors seeking to archive the genocide are forced either to archive those data by hand, or to develop computer programs to scrape the content systematically. Each of these approaches involves daunting technical and personal risks.

Archiving By Hand

For teams archiving the genocide content by hand, such as TikTok Genocide or volunteer efforts supporting Al-Haq, content must be systematically saved and tagged by teams of volunteers. Volunteers work for free, giving up hundreds of hours of their spare time outside of work, as there is little to no funding or institutional support for this kind of labor. These teams must coordinate with each other, splitting up tasks and holding regular meetings to refine methodology. To protect their identities, they use VPNs, communicate with each other via secure messaging apps, and occasionally withhold their identity when communicating with other teams. Perhaps the greatest challenge of manual archiving is that volunteers must watch the videos and look at the images themselves, many of which are very graphic and traumatizing in nature.

Archiving With Scrapers

In this regard, developing scrapers – computer programs that hoover up content from social media – is a great advantage, insofar as the human need only consume the content incidentally or occasionally, while letting the machine consume and file away the majority of content. Since scrapers can work tirelessly 24/7 to comb social media, a scraping approach also holds the promise of covering more ground and faster. For example, one of the largest manual archiving efforts I have encountered is TikTok Genocide, whose team has already archived over 10,000 videos by hand as of March 2025. Over a shorter period, however, the Instagram scraping solution pursued by SaltPillar has archived an estimated 300,000 videos and over 1 million images so far.

That said, scrapers carry a unique set of risks and challenges. Scrapers are computer programs that log into a social media app (Instagram, for example) and navigate through it, collecting data as they go. This kind of automated account activity is generally frowned upon by the social media companies, who expect users logged into their apps to be real. Account automation is often forbidden by an application’s terms of service, so scrapers run the risk of legal action.

Additionally, platforms often take measures to resist scraping, suspending accounts that behave in a seemingly automated fashion. When developing scrapers, one has to modify the flow of the program to circumvent these defenses. For example, SaltPillar’s Instagram scraper masks its internet address and logs into Instagram using fake accounts, then paces its activity to avoid triggering anti-scraping defenses.

Scrapers are also sensitive to the user interface (UI) of the application, and their functionality can be undermined by minor changes as applications are updated. This means that scrapers are high-maintenance software requiring care and vigilance from developers. This ultimately limits their scalability.

All of this means that scrapers are not easy to develop, especially when they need to run at scale and be robust to internet outages, UI updates, dodging anti-scraping defenses deployed by the platform, and so forth. Even where there is a willingness and energy to contribute to archiving the Gaza genocide, not many members of civil society have the skill set to develop scraping solutions. Indeed, as of the time of writing, SaltPillar is the only project we know of that has developed an Instagram scraper.

Conclusion

The Gaza genocide is a watershed moment in the history of the 21st century. In the context of a comparative news vacuum in Gaza, local journalists and content creators have risked their lives and limbs to document the atrocities. In this regard, social media has proven itself an indispensable tool for broadcasting the violence and hardship to international audiences, while creating a digital record of these seminal events. Even as social media platforms have shrugged stewardship of the data, independent civil society actors have stepped into this technical and moral void, developing tools and methods on the fly to archive content for posterity. Though fraught and fragmented, these efforts are indicative of the goodwill people all across the globe hold towards Palestine, their extra-institutional commitment to justice, and the enduring potential of digital technology to be repurposed for the cause of liberation.