In Parallel to Ground Operations in Sudan, Hemedti and Al Burhan Fight it Out Online

This is part of a series of investigative reports published in collaboration with Daraj media

Supporters of both sides of the fighting in Sudan used social media networks to amplify their version of what is happening on the ground. To that end, both sides utilized various tools, including rallying behind hashtags, relying on fake accounts, misinformation, and rumors.

On 15 April 2023, armed clashes erupted in Sudan between the Sudanese army and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (R.S.F) - two allies of the post-Omar Al Bashir transitional period - triggering a massive parallel mobilization in virtual space. Observers attribute the cause of the clashes to the exacerbation of the rift between the head of the Transitional Sovereignty Council, and commander of the Sudanese Army, Abdel Fattah Al Burhan, and his deputy, the commander of the R.S.F, Muhammad Hamdan Dagalo, known as “Hemedti”; in addition to increasing pressure by the military on Al Burhan to dismantle Hemedti's forces in light of R.S.F’s growing influence that is largely derived from regional support.

Supporters of both sides of the fighting turned to social media in order to amplify their version of the happenings on the ground, utilizing different tools, including rallying behind hashtags, relying on fake accounts, misinformation, and rumors.

In our analysis, we monitor the online presence of the two parties and interactions related to the ongoing developments in Sudan, to try to find out who might be behind this activity, and the operating mechanisms of these influence campaigns.

What happened?

About a month before the outbreak of clashes, a dispute arose between Al Burhan and Hemedti around some of the provisions of the framework agreement that complements the political transition process in the country. This was caused by a divergence of perceptions on how to integrate the R.S.F, the size of which is estimated by analysts to be more than 100,000 soldiers.

According to press reports, the Sudanese army wanted the RSF to be integrated within two years, while Hemedti insisted on 10 years. Rumors and speculations spread about the imminence of a possible clash, and this was reinforced by confrontational statements from leaders on both sides for weeks on end. As the clashes began, supporters of both parties used propaganda in an attempt to sway the general public through coordinated online efforts that were in parallel to the hostilities on the ground.

Bots and repetitive content

The online climate of interactions related to the recent events in Sudan reveals a careful and coordinated effort to control the prevailing narrative during the armed clashes in the country. The situation seems similar to that accompanying the attack on Tripoli by retired Libyan general Khalifa Haftar, commander of the “Libyan National Army” in eastern Libya in 2019.

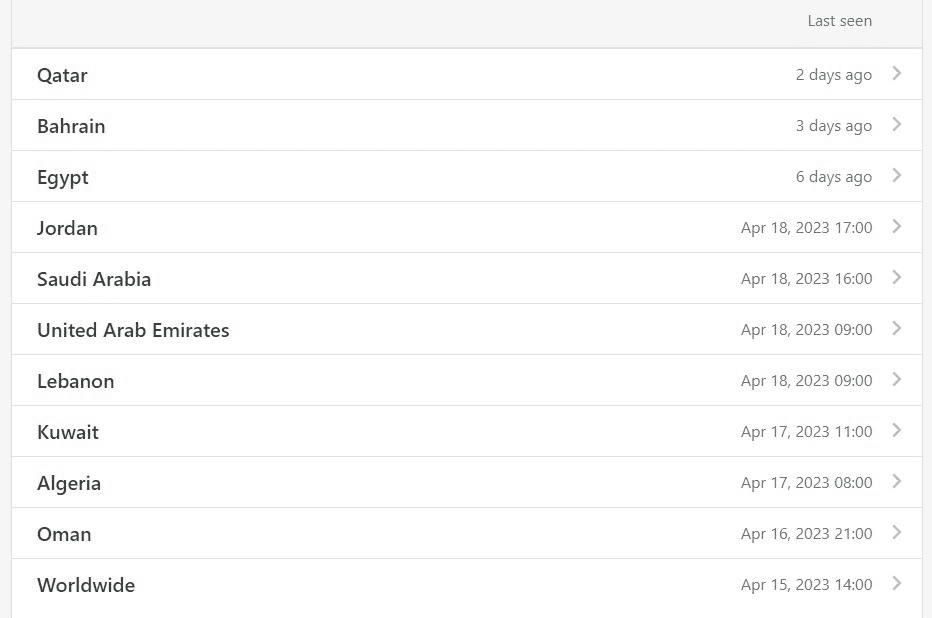

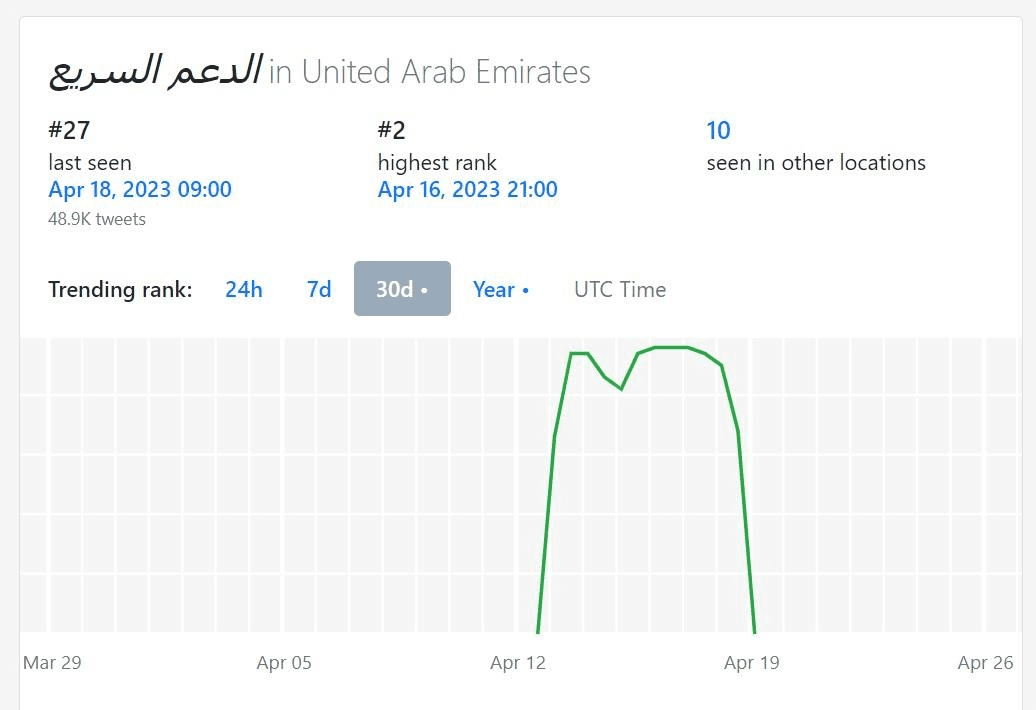

These efforts ranged from issuing real-time data on developments on the ground through social media posts, to the use of armies of fake accounts (bots), and the dissemination of repetitive content and misleading information.The campaign in favor of the RSF has maintained the momentum of discussions around the RSF since the recent outbreak of events on April 15th. On Twitter, at least 48,900 tweets were about the RSF. The topic remained dominant in at least 10 Arab countries, where most of the tweets came from. According to Get Day Trends, these countries are Qatar, Bahrain, Egypt, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Lebanon, Kuwait, Algeria, and Oman.

As confrontations continued on the ground, a group of fake accounts contributed to the RSF remaining topical, until tweeting reached a climax between 12 April, when there was talk of RSF movements towards the Marawi Air Base, and 19 April, before the tempo of interactions subsided amid international efforts to cease the fighting.

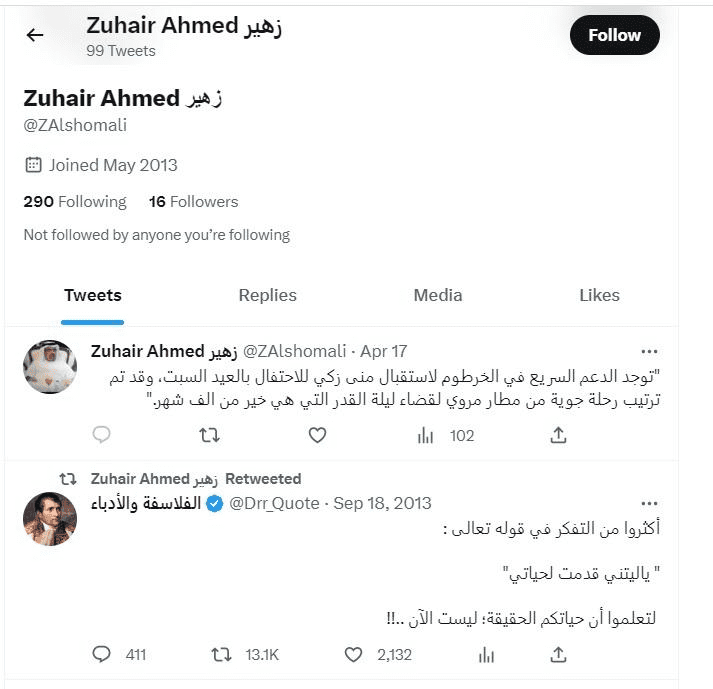

In addition to classic news coverage from news outlets, the fake accounts generated a large number of tweets during this time period. Noticeable is that a large percentage of these accounts are old, most of them created in the years 2011, 2012, 2013, and 2014. These accounts have little followers, the largest of them with only a few dozen followers.

Neither do they have a lot of tweets, as some have only posted in relation to RSF, while others tweet in different languages, including English, Latin, and other Asian languages. This could indicate that these accounts were part of cheap e-marketing campaigns, which typically use bots that spam repetitive tweets to promote a certain product, and the content of which is typically deleted afterwards until the next marketing campaign.

Another possibility is that these accounts are used in campaigns with political purposes, or that some of the accounts were stolen from their original owners, especially since some of them have not tweeted since 2013, and the first new tweets were about the RSF. See the example below.

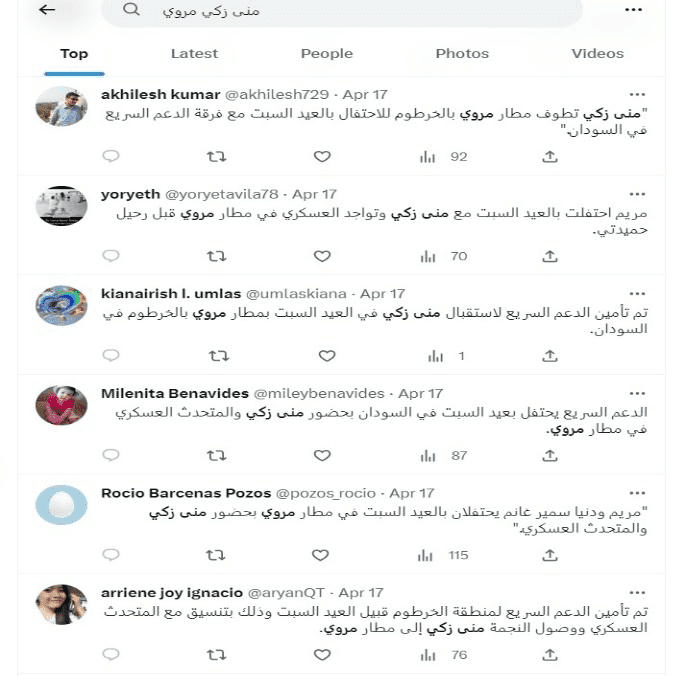

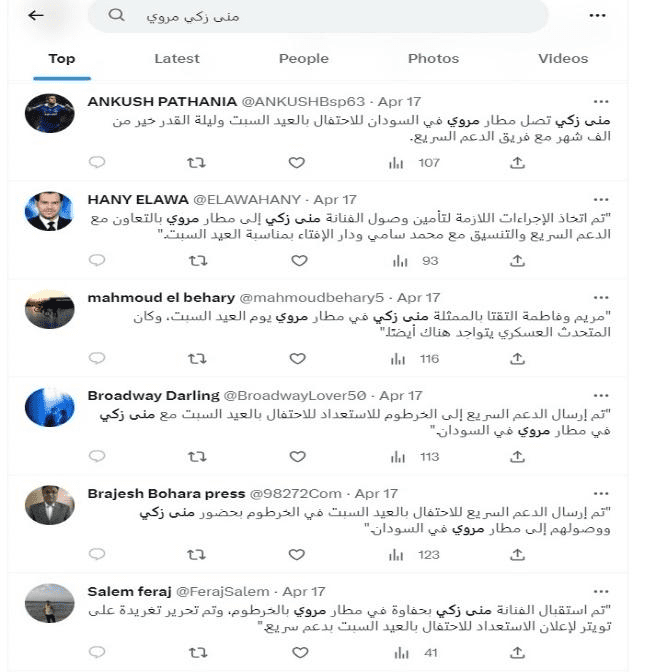

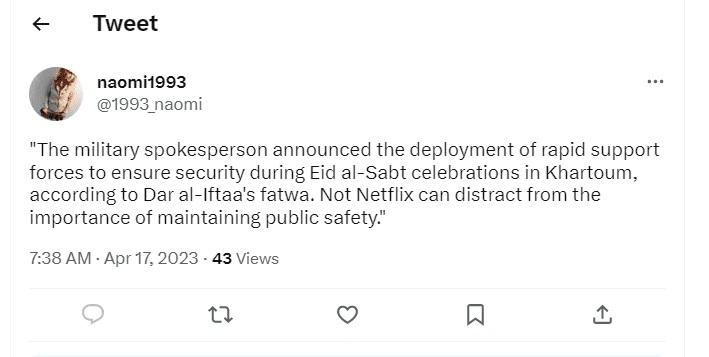

The accounts bear Arabic, English, Indian and Spanish names. Some posted tweets in Arabic, others in English mentioning the phrase “Rapid Support Forces.” This tactic was used by Gulf supporters of General Khalifa Haftar in Libya, when he attacked Tripoli and deployed an electronic force that launched from Twitter , and published content on websites and through tweets in Arabic, English and French. The content of the RSF tweets was inconsistent, as if someone was trying to capitalize on the most popular keywords to help amplify discussion around the RSF.

As the situation erupted in Sudan, attention turned to Khartoum and the Marawi base, especially with the detaining by the RSF of Egyptian forces who were present to participate in training with their Sudanese counterparts. There seemed to be an attempt to draw attention to these hotspots and make political use of them, even if the tweets themselves were incoherent.

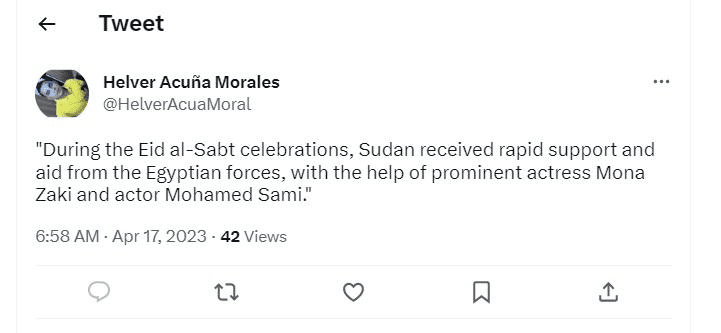

For example, the text of one of the repeated tweets reads: “Mona Zaki and Donia Samir Ghanem celebrate Eid on Saturday at Marawi Airport, with prompt support from Sudan.” While another tweet read: “The RSF in Khartoum has moved to receive Mona Zaki to celebrate Eid on Saturday, a flight was arranged from Marawi Airport to spend Laylatul Qadr, which is better than a thousand months.”

We cannot directly pinpoint the parties behind the fake accounts campaign in Sudan, but previous investigations revealed the involvement of Russian and Emirati networks in influence campaigns in Sudan. The latest such campaign was revealed by an investigation conducted last February by the Sudanese website “Beam Reports” which is concerned with verifying news.

At the time, Beam Reports revealed a network of fake active Twitter accounts in the tens, publishing positive tweets about the role of the UAE and its economic projects in Sudan, while attacking influential civil groups. Among the hashtags that were used by that network are # Sudan Is In UAE’s Heart, # No To Freedom & Change, # Mohammed Bin Zayyid Al Burhan, # Enough With The Chaos Of Freedom & Change.

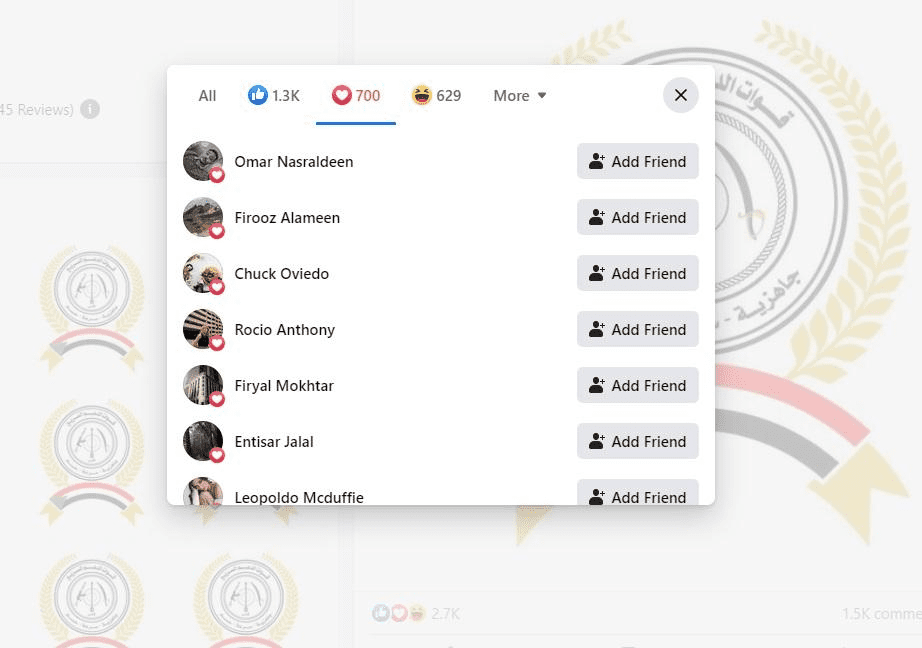

Fake accounts were also used on Facebook, especially on the RSF’s official page, which has a following of 984,000. Certain accounts kept popping up in interactions on the page’s posts, exceedingly using the ‘love’ reaction. Several of these accounts which interact with Arabic posts, had non-Arab sounding names, mostly female names, and used stock photos for their profile pictures.

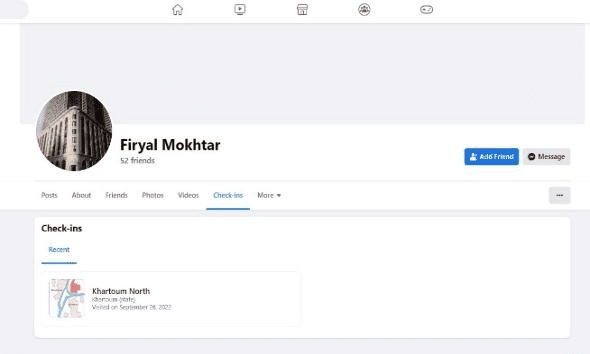

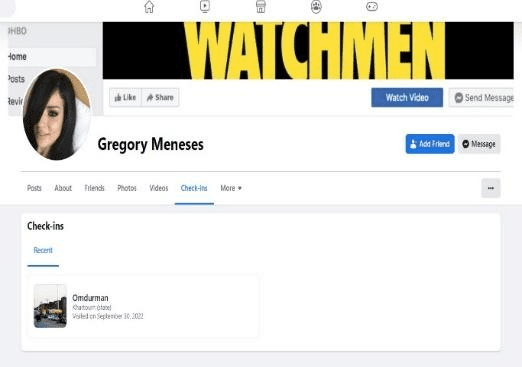

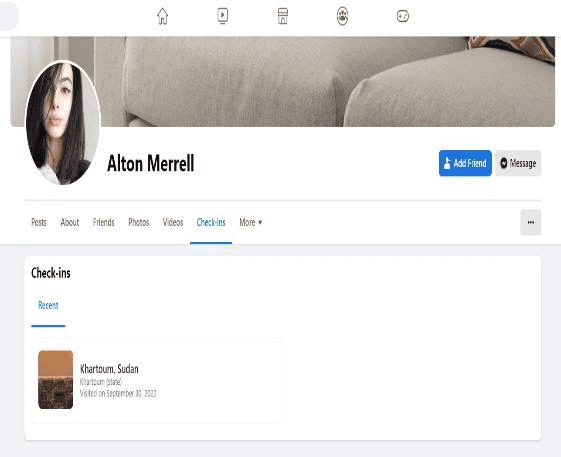

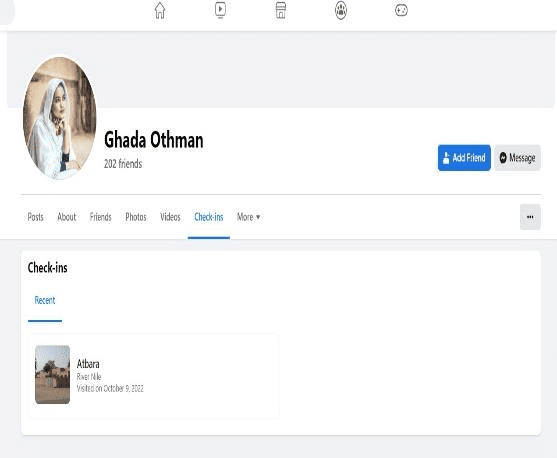

Another suspicious gesture was that the accounts we suspected had all used Facebook's "Check-in" feature so that they could be located in Khartoum. This was over certain time periods, mostly in late September and early October. This could be interpreted as an attempt by those behind this network to make the accounts appear as though they are owned by real people.

We also noticed that these accounts, which bore foreign names, had participated in interactions with the RSF, publishing the same content but with minor changes.

Cross-posting repetitive content on different platforms

The frequency of interactions reveals the existence of duplicate cross-platform content on Twitter and Facebook. Remarkably, this content was repeatedly posted between pages and accounts supporting the RSF.

The following text moved between Facebook and Twitter with the participation of accounts that appear to be supportive of the RSF: “It was not enough for Al-Burhan to murder his people and soldiers of the armed forces by using them as fuel for his war with the remnants of the regime, traitors and agents, he has [now] transitioned to another level, which is starving them to death.”

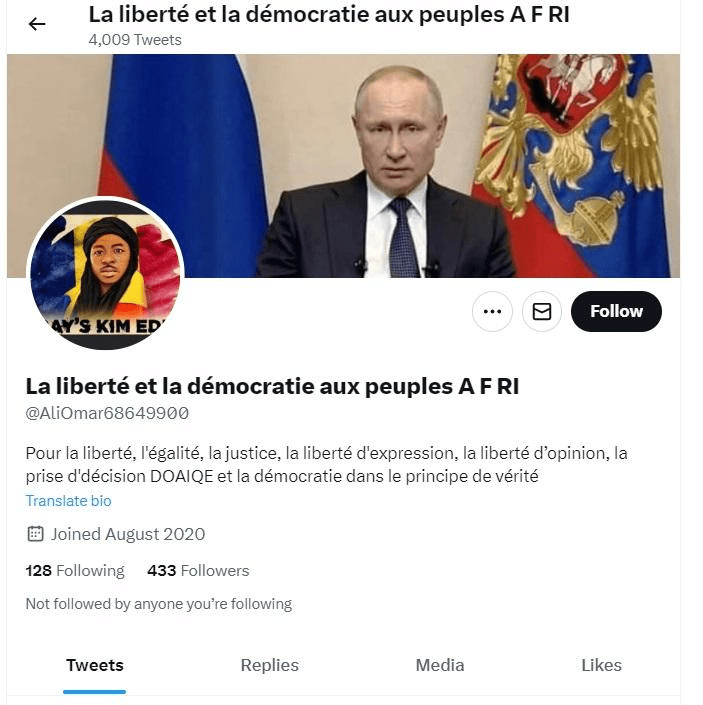

Twitter accounts posted the same content, but we have noticed this account in particular, @AliOmar68649900, which appears to be owned by someone who lives in Chad. His avatar also comprises the colors of the Chadian flag. The account is focused on posting tweets in support of RSF, as well as sharing popular Facebook posts to Twitter. His header photo is a picture of Russian president Vladimir Putin.

There were also Tik Tok videos of persons which show that they are either in Chad or Niger. Some published videos in support of the RSF, such as this account @djimaamahamat, which posted an interview that went viral with a group of “Niger Arabs”, who expressed their support for Hemedti’s forces and their willingness to support him.

UAE operated accounts.. Hemedti and a mental image of a savior

RSF head, Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, employed a large promotional campaign in recent years in order to win over Sudanese sympathy. This came in light of his evident ambition in leading the country. Social media networks are a cornerstone of Hemedti’s campaign, and he and his campaign managers heavily rely on social media in order to amplify his virtual presence and cherry pick excerpts from his statements. Dagalo owns different accounts on social media networks. His first online presence was through Hemedti’s Facebook page on 20 April 2020. His Facebook followers are now at 780,000, while he has 207,000 Twitter followers.

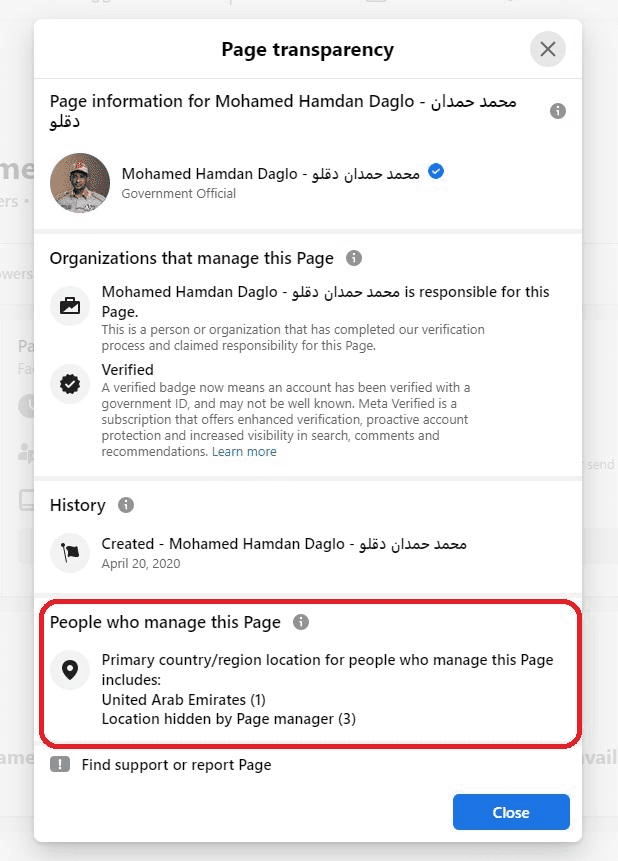

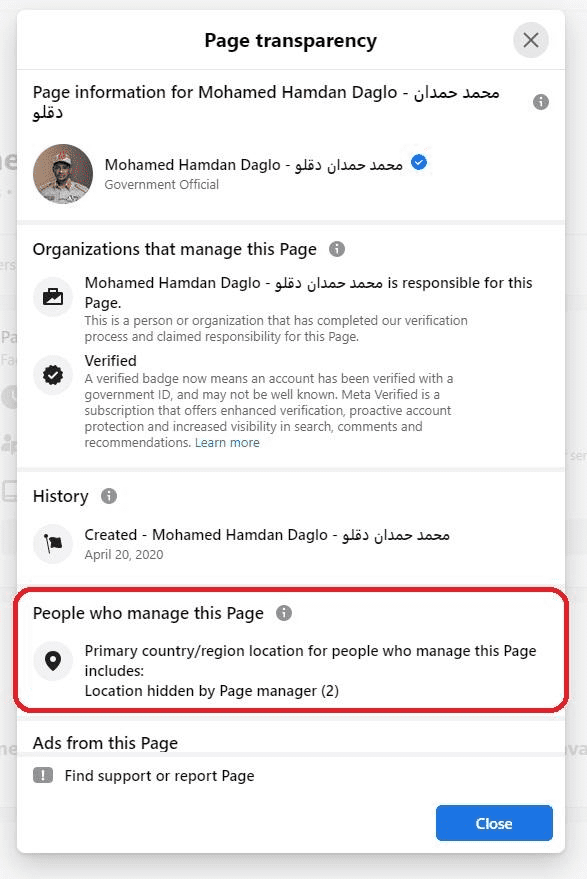

As events erupted in Sudan, many started taking notice of Hemedti’s page on Facebook. The transparency feature on the platform shows that the page is run by persons or entities located in the UAE and three other anonymous locations. As questions increased over the issue of the page being run from the UAE, the page hid or removed the account with a UAE location.

One of Hemedti’s pages on Facebook was removed but it was clear from other indicators that a number of his page administrators are located in the UAE.

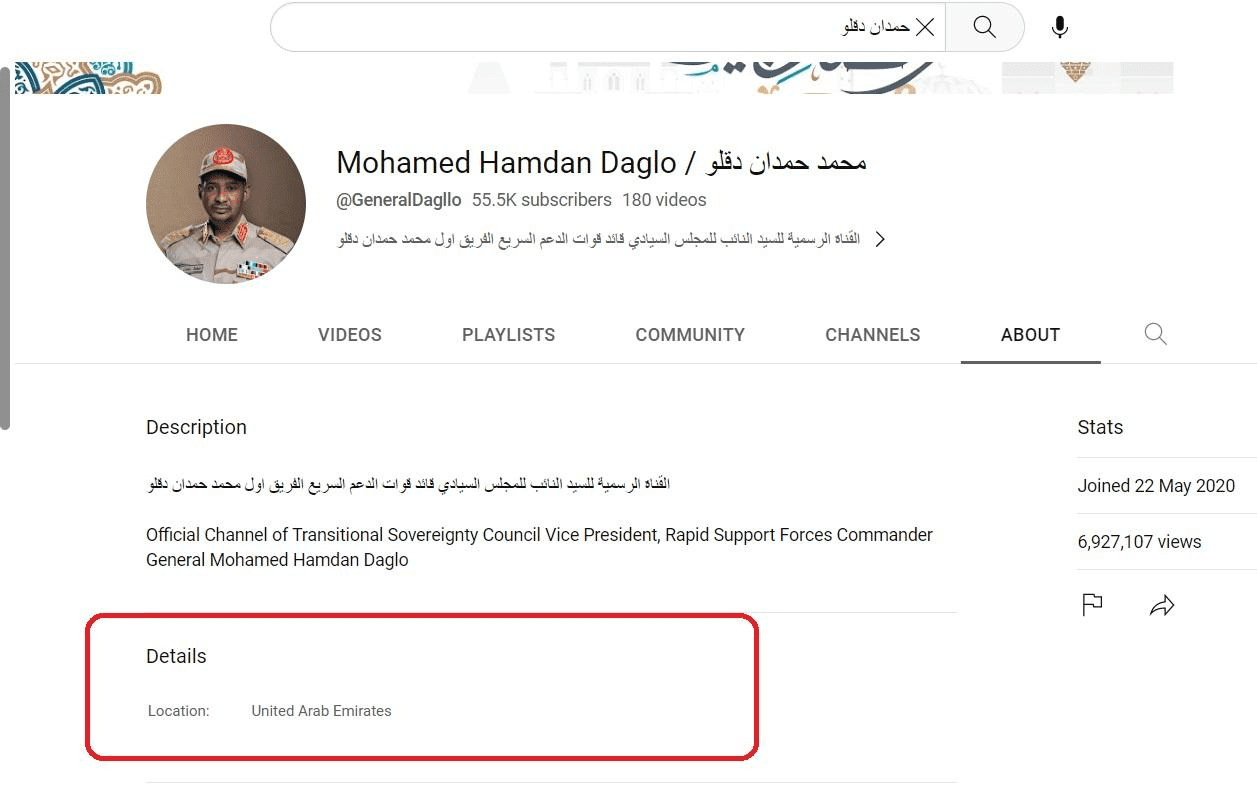

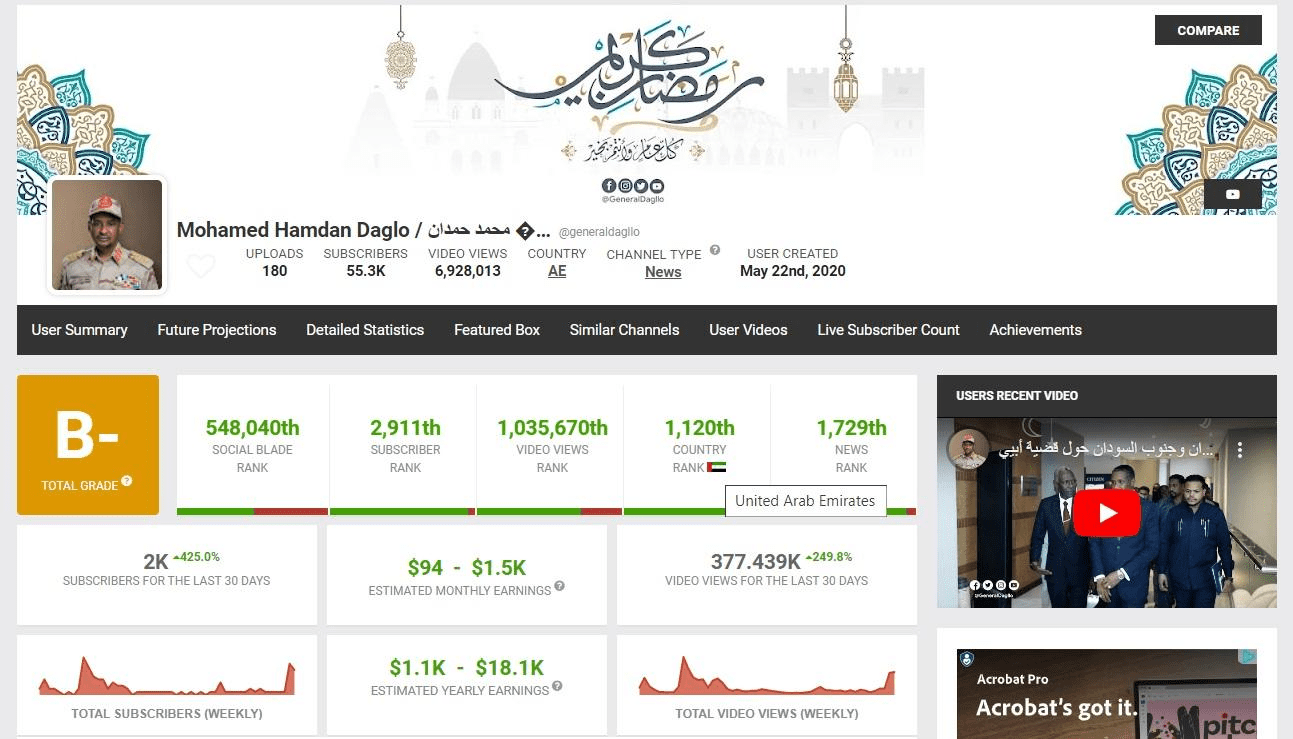

Hemedti’s Youtube channel with 55,000 subscribers, shows that its administrators are located in the UAE. Social Blade, a website focused on social media monitoring, confirmed that Hemedti’s Youtube channel is run from the UAE. The website ranked it at number 1120 in the UAE in comparison with other Youtube channels. According to Social Blade, the channel had over 377,000 viewings in the last 30 days, and a total of 1 million viewings of the 180 videos that are posted on the Youtube channel. All of this has increased interest in the channel with the developments in Sudan.

Screenshot from Social Blade showing Hemedti’s Youtube channel data.

On 1 June, when the RSF page appeared on Facebook, the transparency feature showed that the page was run by persons in Sudan, the UAE and Saudi Arabia. The page has 984,000 followers. Created in January, RSF’s Twitter account has over 99,000 followers.

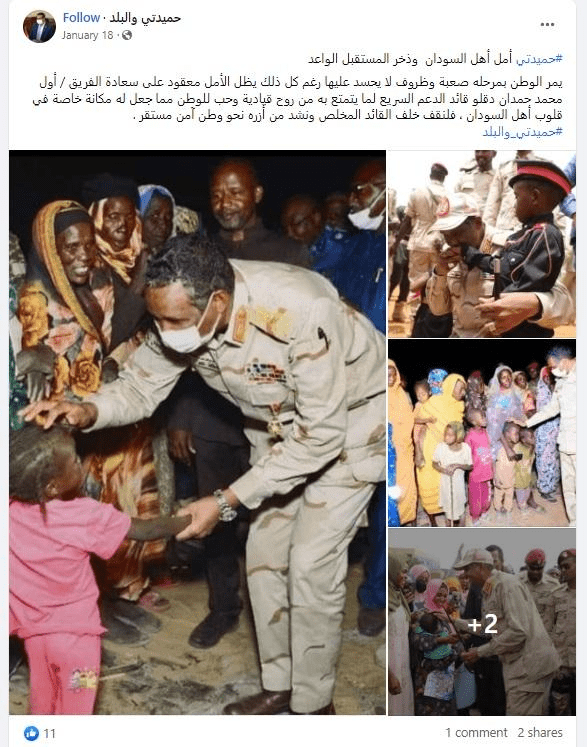

In addition to his accounts on social media and the RSF pages, Hemedti relies on a heavy artillery of accounts, pages, and groups that operate in concert in order to polish his image and amplify conversations about him in Sudan. In repeated posts, he is pictured as Sudan’s hope in overcoming its struggles, and depicted as its savior. Reports revealed that Hemedti met last year with representatives from Think Doctor, the PR company, in order to help him wash his image in Europe. The company is also thought to have assisted him with media and social media training.

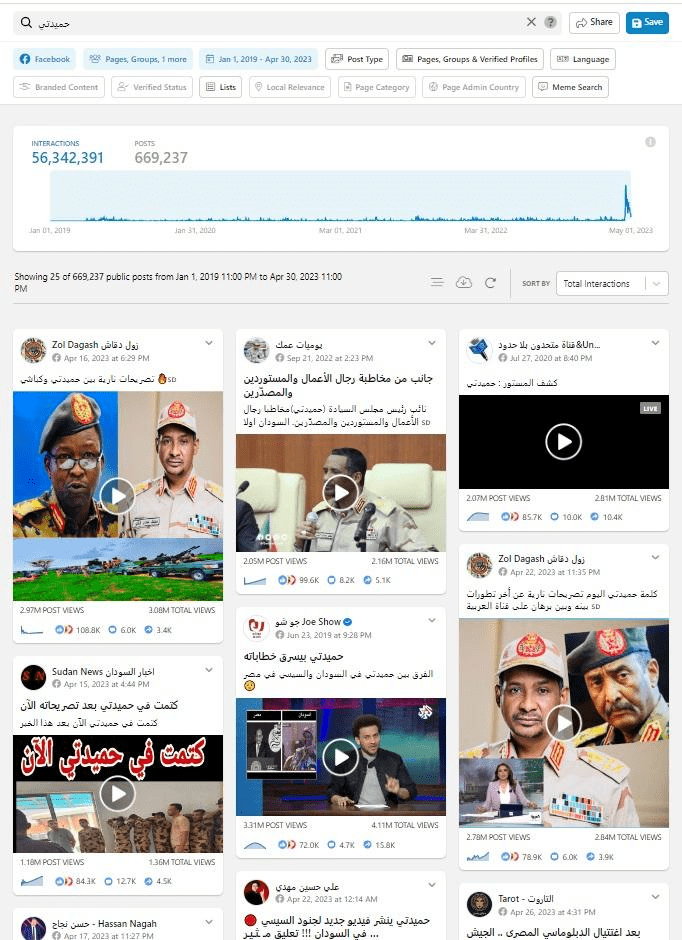

Data collected from Facebook’s Crowd Tangle gives us a glimpse of the sheer size of Hemedti’s electronic campaign and his large online presence. Between the beginning of 2019 and the end of April 2023, there were a total of 669,257 Facebook posts with a mention of Hemedti’s name. These posts saw a total of 56 million interactions. Public groups - which Crowd Tangle was able to detect - played a large role in spreading Hemedti’s promotional messages. These pages alone were responsible for about 489,000 posts about Hemedti, with a total of 10 million and 558,000 interactions. In just one month of fighting (April 2023) there were 73,337 posts with Hemedti’s name that generated 12 million and 441,000 interactions. On the other hand, the RSF was mentioned in more than 731,000 posts since 2019, generating 66 million and 539,441 interactions.

Screenshot from Crowd Tangle showing the Hemedti name statistics from 2019 to date.

Last March, Hemedti made announcements that carried a different tone, as he demanded the cleansing of the Sudanese military from Islamists. The statement came in parallel to the conflict around merging his forces into the Sudanese army. Hashtags started appearing after the clashes started, attacking the Islamist movement in Sudan, and describing it as terrorist, suggesting that Islamists are behind the latest escalation of the conflict between the Sudanese army and the RSF, in an attempt to return to power. The Islamist movement is seen as a cornerstone of Al Bashir’s time in power and the base that he relied on throughout.

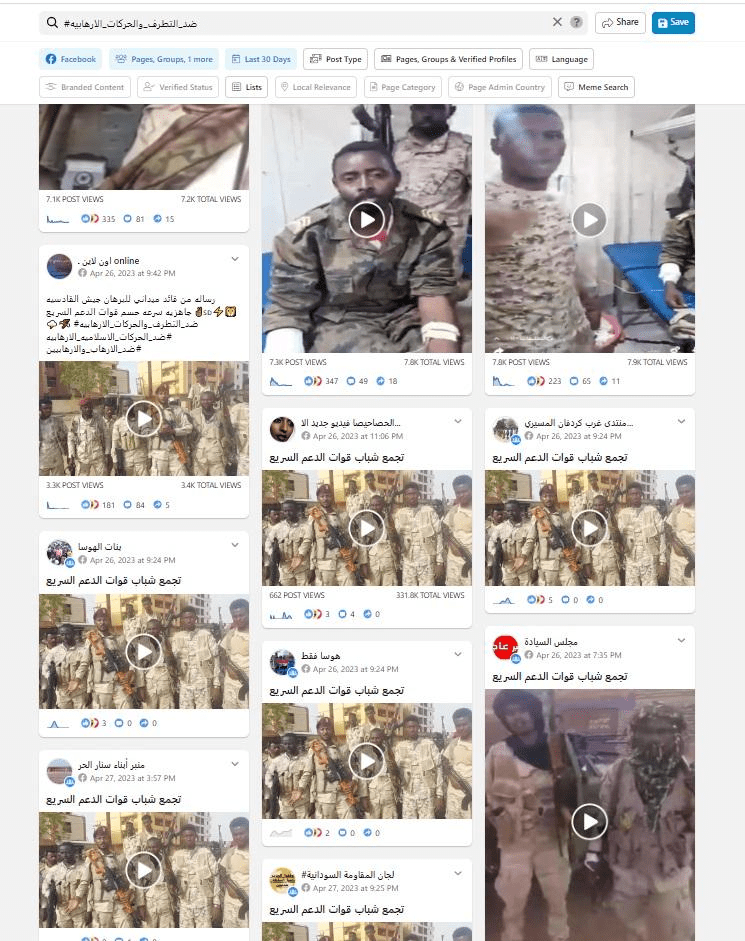

One the hashtags was # The Islamist Movement is a Terrorist Organization, which became active after the clashes and, according to Facebook statistics, had 15,000 posts until early May. The group page “Gathering of RSF Youth” reposted the hashtag content created using it.

There was also the hashtag # Against Extremism and Terrorist Groups, with less than 1000 posts, and the hashtag # The National Congress Is A Terrorist Group, in reference to the ruling party at the time of Al Basheer.

Al Mujahedoon, groups and pages driving the momentum on Facebook in favor of the army

On the other hand, hashtags also emerged in support of the Sudanese army and its movement against the RSF. Facebook groups and pages were used to enhance the army’s narrative on developments on the ground and in mobilizing the streets in the army’s favor.

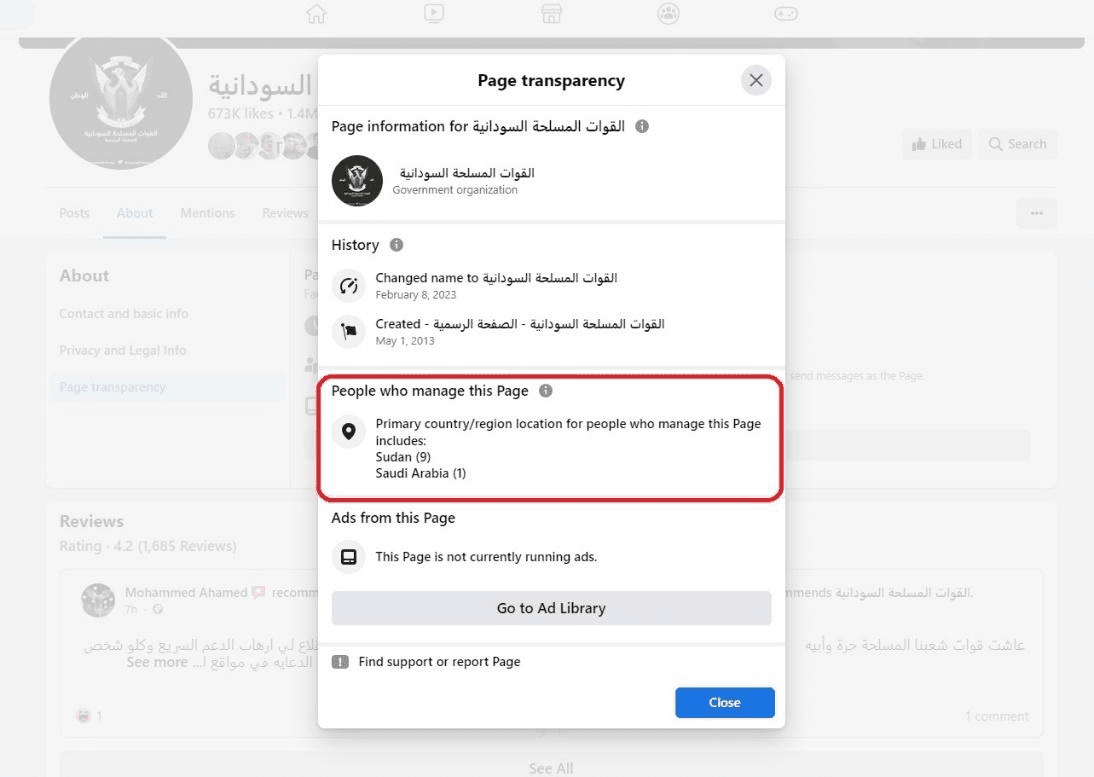

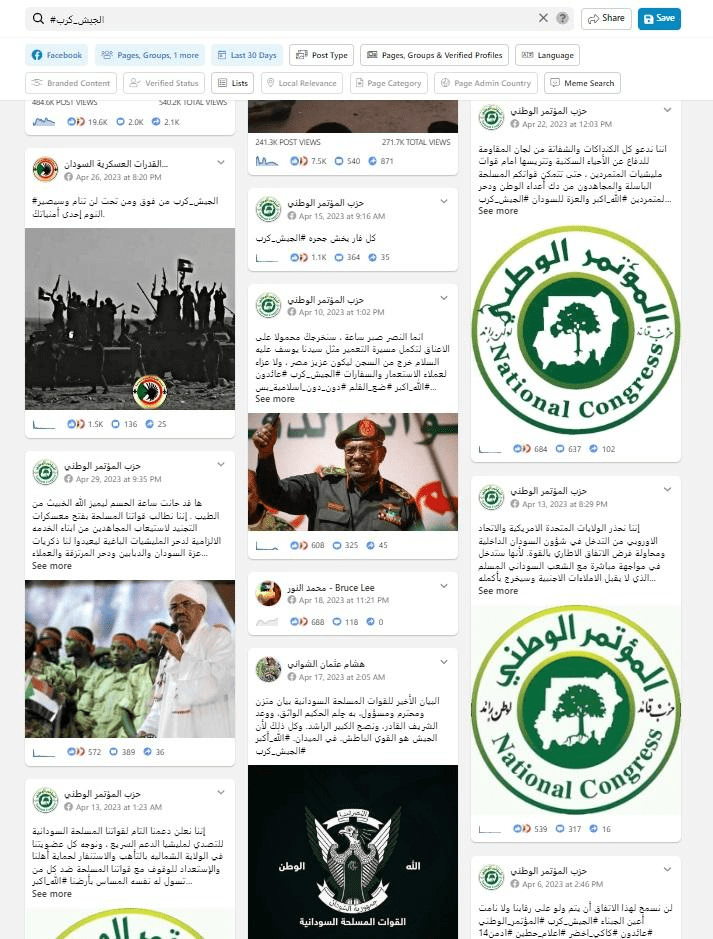

The Sudanese Armed Forces page played a large role in promulgating hashtags in support of the Sudanese army. Being the page for the army’s spokesperson, media outlets largely rely on it for information on the armed forces. The page has over 1.4 million followers, and is administered by 9 accounts operating from Sudan, and one from Saudi Arabia (according to Facebook’s transparency feature).

The page contributed to the promulgation of the following hashtags: # The Army Is Aware, # Ending The Rebellion, # One Army One People, and # ده_جيش_بتداوس, which garnered tens of thousands of posts according to Facebook statistics.

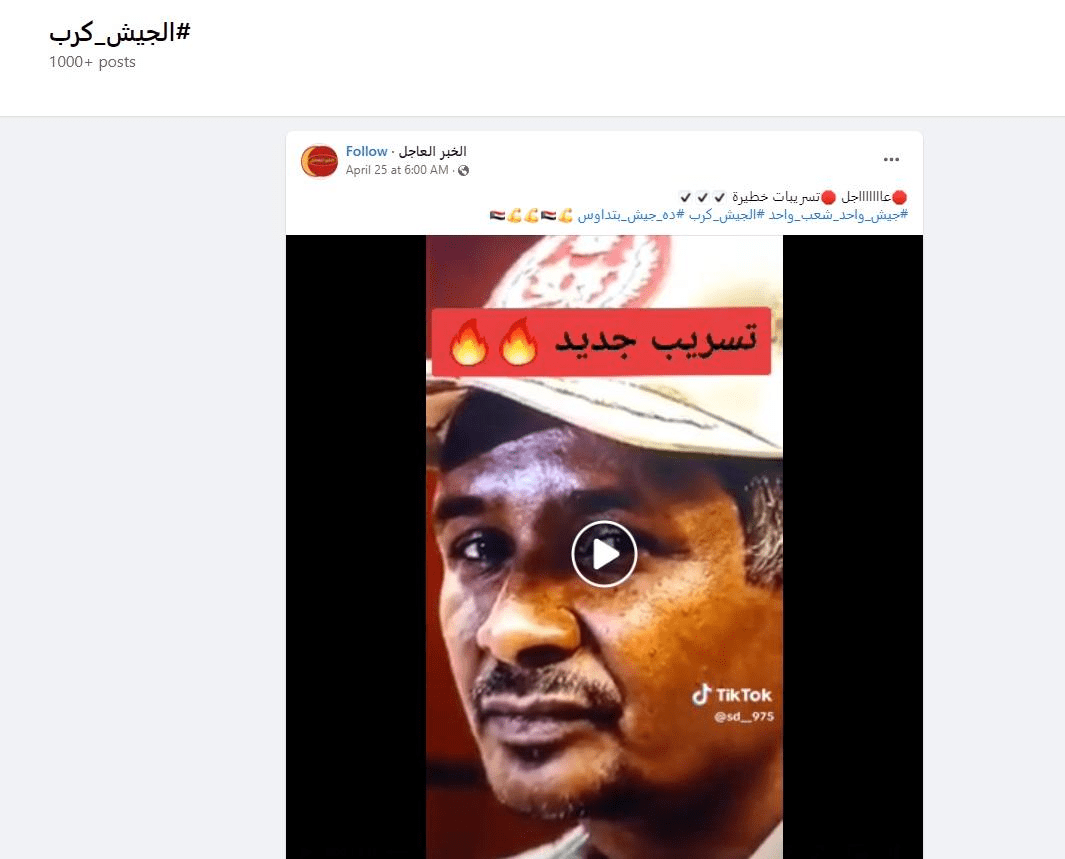

Other hashtags in support of the army became active on Facebook, such as # Anguished Army, which had more than 1000 posts. Indicators show that this hashtag is related to the National Congress Party (NCP), which was the ruling party in Al Basheer’s time, as well as Islamist men in the army, who are enemies to both the revolutionary forces and Hemedti’s forces. The hashtag promoted misinformation and rumors, in addition to what was called “leaks”, which were voice files with a background photo of Hemedti.

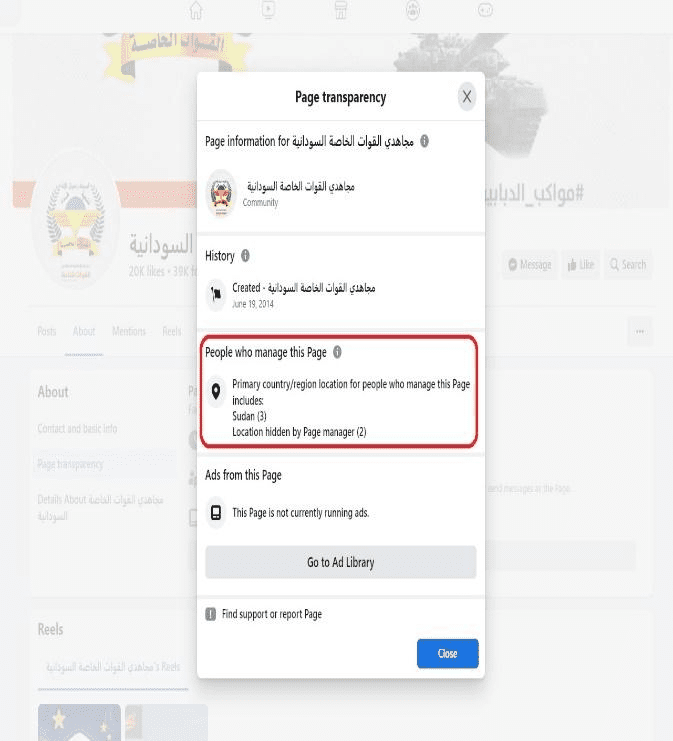

We noticed that some of the posts under the hashtag contained the “Special Forces Mujahideen Media Network” which refers to a Facebook page and group linked together by the same name.The Mujahideen page is managed by 3 accounts inside Sudan and two accounts from unknown locations outside the country. One officer named Muhannad Karam runs the group in addition to the page.

Crowd Tangle helped us identify another remarkably active account on the #Army Anguish hashtag, which is the NCP, whose name was repeated in posts. The Party's page, followed by 87,000 people, manages 3 accounts based in Sudan, an account from France and another in Britain. The page called for the release of Omar Al Bashir, who is imprisoned on charges of corruption and wanted by the International Criminal Court for atrocities committed in the Darfur conflict, which are charges he denies. The page published posts that included pictures of the former Sudanese president, some of which had a caption which read: “Victory is but an hour’s patience. We will get you out of prison held on people’s shoulders so that you may continue the reconstruction process, like Joseph was acquitted from prison to lead Egypt.” There were also posts of expressions of support for the army in confronting the RSF, with some stating “every rat should return to its hole.”

The NCP’s posts on the # Army Anguish hashtag also made references to the possible involvement of the Islamic Movement and the Congress Party in the armed clashes taking place in Sudan. In one of its posts, the NCP wrote: “If Al Burhan cannot deter the RSF rebels, we have men who are able to do it and they will.” The post featured photos of two members of the Transitional Sovereignty Council which are close to the Islamist movement.

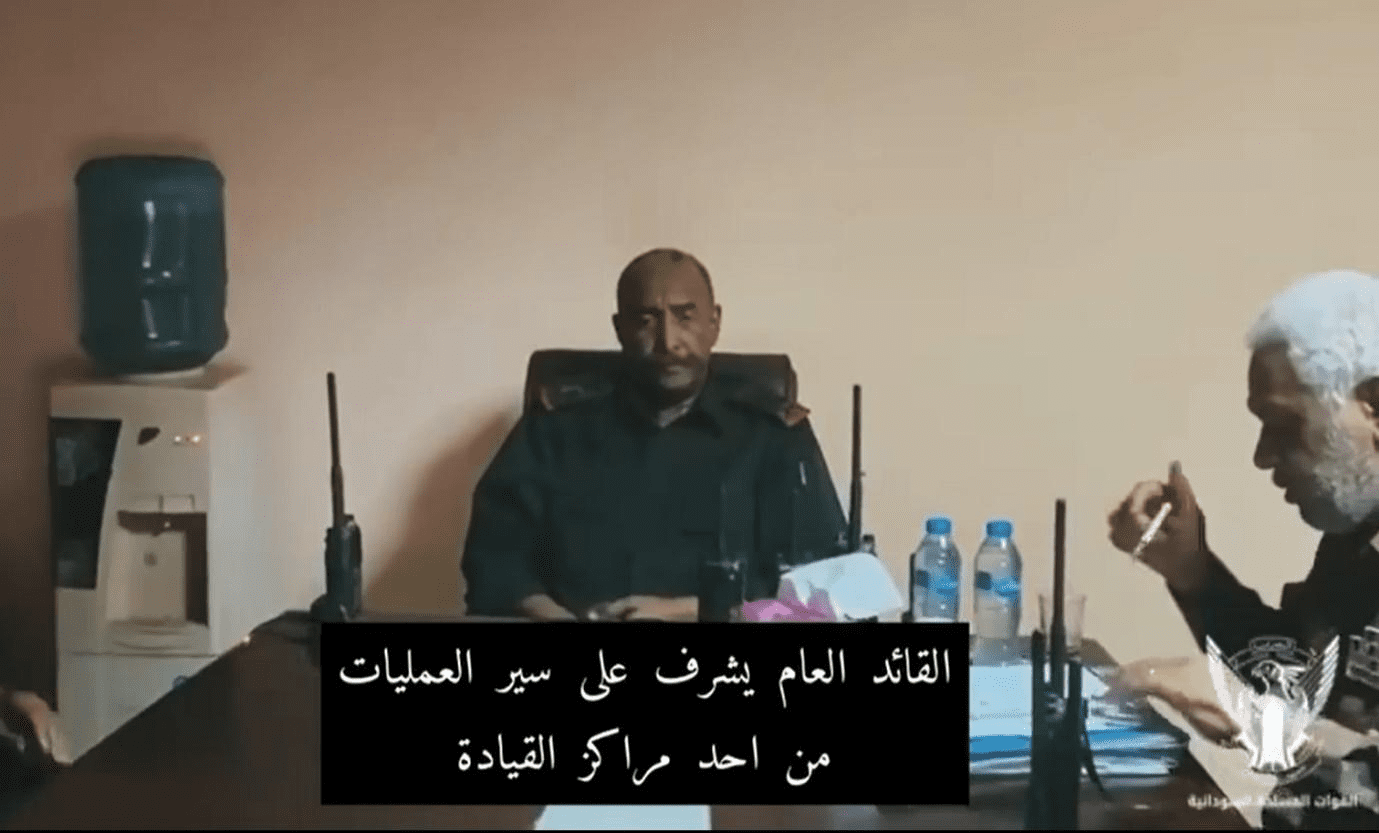

The first person (right of the picture) is General Ibrahim Jaber, described by the Sudanese press as the architect of the return of the Islamist regime, and one of the Islamist allies of Omar Al Bashir. The picture on the left is General Shams Al Din Kabbashi, also close to the Islamists. Reports by the Sudanese press over the past months implied that Kabbashi was a shadow figure behind the scene, and described him as the real controller of the Sovereignty Council, enjoying great influence on Council Head, Abdel Fattah Al Burhan. These speculations resurfaced with the publication of a video on the Sudanese Armed Forces’ page showing Al Burhan with a passive frowning expression during a meeting of the Operations Command, while Kabbashi appeared actively engaged. Questions arose over the reasons for Al Burhan’s facial expression, with comments suggesting that Kabbashi is the one directing the confrontations on the ground against the RSF. However, these all remain to be unconfirmed speculations.

Screenshot from a video posted on the Sudanese Armed Forces Facebook page on 1 May, 2023.

“The Joker Brothers” and “Ansar Al Mukhabarat” .. Khartoum is the cemetery of the Janjaweed

Of the multiple Facebook hashtags supporting the Sudanese army, # Khartoum Janjaweed Cemetery caught our attention. The hashtag has over one thousand posts according to Facebook statistics. The hashtag was launched by a group called “The Joker Brothers”, whose name appeared repeatedly with the hashtag in several posts.The group owns the Facebook page called “Black Box Group”, and defines itself as the “Sudanese Electronic Defense Brigade.”

The term Janjaweed is used to refer to the RSF, given that the militias formed by Al Bashir to control the unrest in Darfur (2003-2005) constitute the core of Hemedti's forces.

The activity of the Joker Brother group, or the Black Box, shows that they possess hacking and cyber operation capabilities. One of the posts stated that the group previously controlled Hemedti’s official media websites.

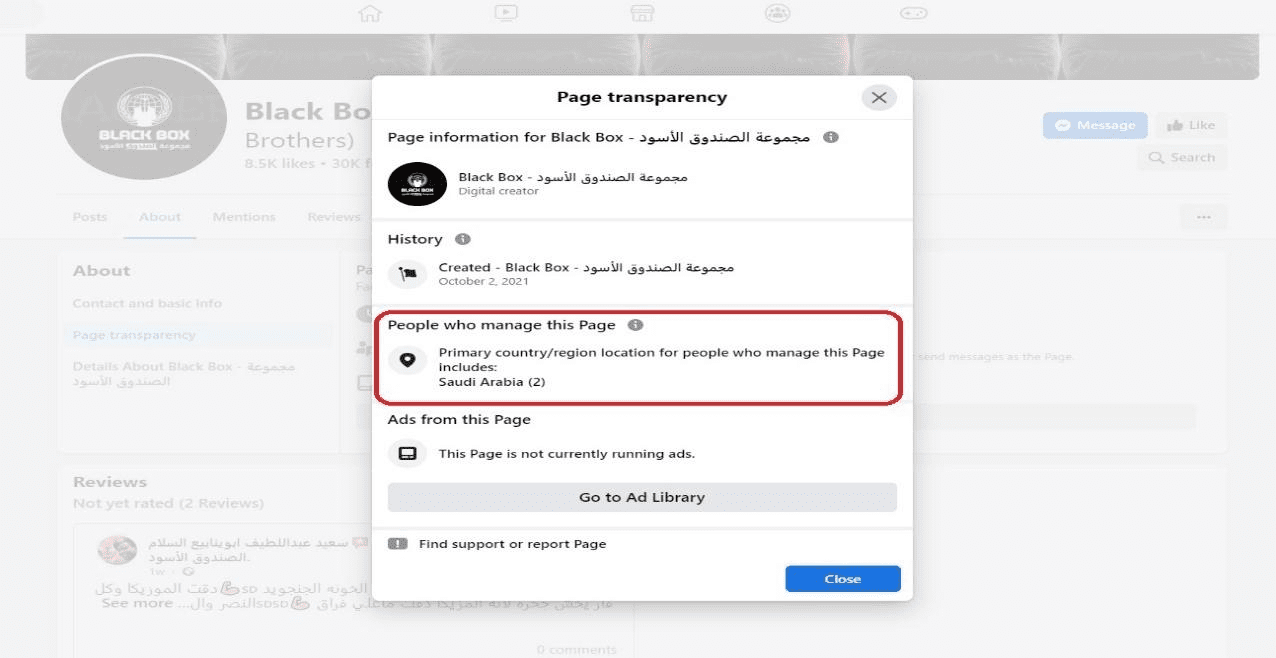

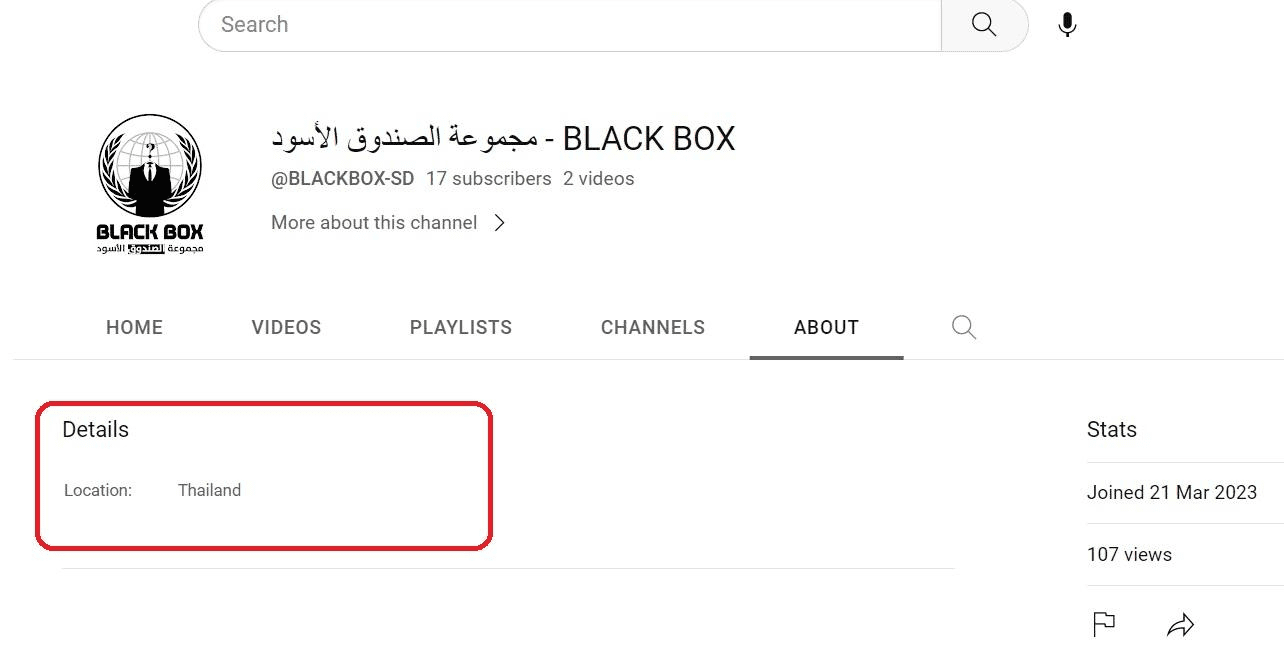

Facebook data shows that the group is managed by two accounts based in Saudi Arabia. The group's YouTube channel indicates it is run from Thailand. The page’s cover photo indicates there are 6 “Jokers'', who may be all that the group is comprised of. One of the persons in the photo appears with his face uncovered.

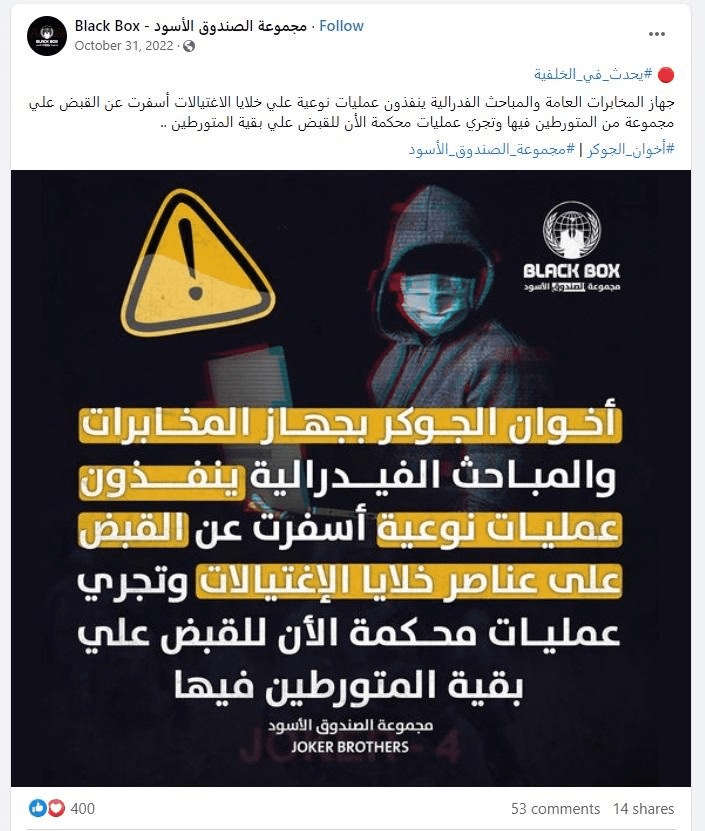

It is not precisely known who runs this group and its pages, but there are some indications that it is linked to the Sudanese intelligence service. A group post stated in October 2022: “The Joker Brothers in the Intelligence and Federal Investigations Service are carrying out operations that resulted in the arrest of members of assassination cells, and controlled operations are now being conducted to arrest the rest of those involved.” Neither the context of the event described nor the subject of the post are clear, but Sudanese followers of the page extensively interacted with the post.

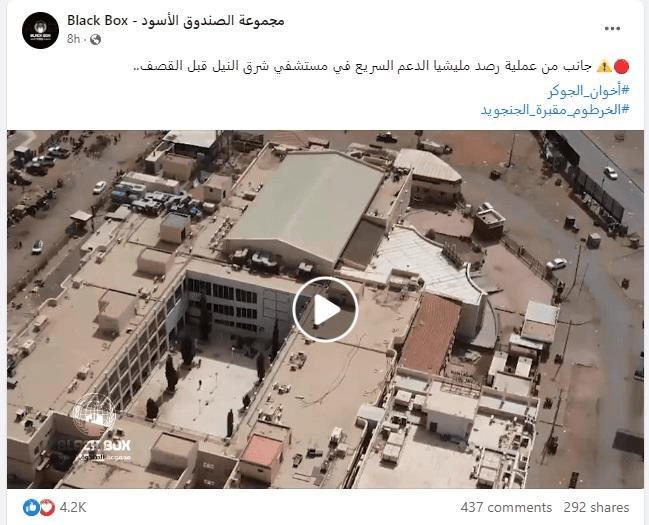

The group and its page’s activity reveal who is behind it. It might just be a group of amateurs or enthusiasts who are employing their advanced cyber knowledge to support the army. The group's page used to publish snapshots and videos bearing its signature and logo. The videos posted on the page were taken by drones and showed what was claimed to be locations of the RSF. The group's page also posted screenshots that included maps.

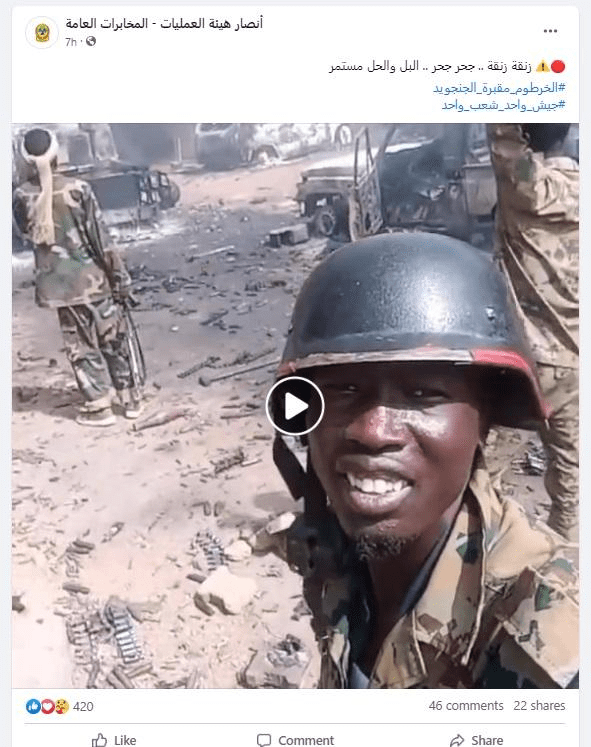

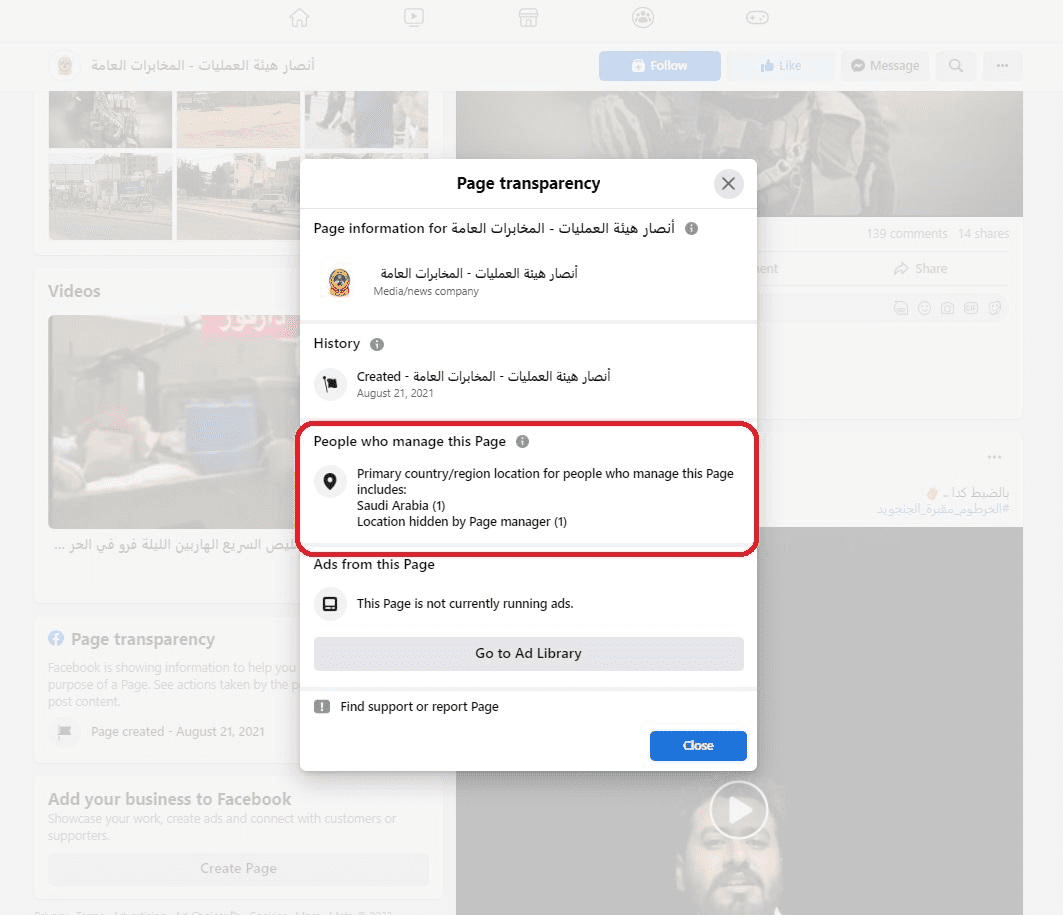

Similarly, the page titled “Supporters of the Operations Authority, General Intelligence Service” was among the prominently active pages on the hashtag # Khartoum Janjaweed Cemetery. This gives a glimpse into the nature of developments on the ground during the clashes, but of course from a pro-army point of view. Similarly, the page titled “Supporters of the Operations Authority, General Intelligence Service” was among the prominently active pages on the hashtag # Khartoum Janjaweed Cemetery. This gives a glimpse into the nature of developments on the ground during the clashes, but of course from a pro-army point of view.

The page has 48,000 followers, and is managed by two accounts, one of is based in Saudi Arabia and the other is anonymous. The page defines itself as “a group of Sudanese youth whose main concern is maintaining social peace in Sudan.”

Wagner, Hemedti Supporters, and Al Bashir: How online activity is related to major events in Sudan in recent years

About a week before the 25 October coup, Facebook stated that it had shut down two large networks that targeted users in Sudan for months. This coincided with escalations in disagreements between civil and military leaders over the future of the power-sharing agreement during the transitional period.

At the time, Facebook said in a statement that one of the networks of inauthentic pages that were removed was linked to the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces, and a report by the Atlantic Council's Digital Forensic Research Lab (DFRLab) indicated that people in the page was run by accounts in the UAE and Saudi Arabia.

The coup took place a few days after Al Bashir's supporters demonstrated in front of the Republican Palace and called for a coup against Abdalla Hamdok's government under the pretext of demanding government reform. The same network contributed to the escalation of calls for civil disobedience in eastern Sudan, and the reinforcement of the Beja Glasses protests in the region, according to statements made to Reuters by Head of Research at Valent Projects, Zouhir Al Shimale.

In early October, Facebook said it had shut down a network of nearly 1,000 accounts and pages with 1.1 million followers run by people Facebook said were linked to the RSF. Facebook also took down a second network in June, after it was tipped off to look into activity linked to Bashir loyalists. The network has more than 100 accounts and pages and over 1.8 million followers.

Facebook also revealed that it had removed two networks in December 2020 and May 2021, saying that they were working to promote Hemedti and the RSF, which was also issued in a DFRLab report.

Facebook found links between the two networks and the Russian Internet Research Agency (IRA), the group accused of meddling in the 2016 US elections. In October 2022, DFRlab analyzed a video showing a Wagner Group leader training the RSF.