Dr. Asma Hedi Nairi

is a researcher and human rights activist based in Turkey, specializing in migration studies, diaspora studies, and discourse and communication analysis. Currently investigating populist narratives, social and mainstream media biases, disinformation, and their impact on people on the move and migrant communities in the Middle East.

Historical Prejudices and Modern Misinformation: The Reproduction of Anti-Arab Sentiment in Turkey’s Online Discourse

Turkey is home to a sizable Arab diaspora, estimated to be millions of individuals originating from various Arab nations, including significant populations from Syria and Iraq. This community has expanded notably in recent decades, particularly in response to regional conflicts such as the Syrian civil war, which has driven millions to seek refuge in Turkey, as well as changing Turkish foreign policy towards the Middle East which has made it a new destination for different Arab nationals.

The historical relations between Turks and Arabs are multifaceted, rooted in centuries of shared cultural and political interactions during the Ottoman Empire and evolving through the modern Republic of Turkey’s formation. While there have been periods of cooperation and cultural exchange, underlying tensions and prejudices have also existed and clearly increased in the past decade, influenced by socio-political changes and economic factors. The integration of Arabs into Turkish society has been shaped by both opportunities and challenges, reflecting a complex interplay of acceptance and resistance within different segments of the population.

In recent years, anti-Arab sentiment in Turkey has surged, driven by multiple interrelated factors, some rooted in historical origins and others emerging from contemporary socio-political dynamics. Turkish-Arab relations and the origins of specific stereotypes will be explored in the following sections; however, it is important to clarify that the significant presence of Syrian refugees and other migrants from different Arab nationalities has intensified competition for resources, employment, and social services, fostering resentment among some Turkish citizens. Economic strains exacerbated by global and regional instability have further fueled xenophobic attitudes, as locals perceive Arab migrants as competitors for livelihood opportunities or a main reason for the high inflation rates especially in the real estate sector.

Additionally, political rhetoric has played a crucial role in amplifying negative perceptions, with nationalist discourse often portraying Arabs as a threat to national identity and security. Media narratives, both traditional and digital, have reinforced these biases, creating an environment where xenophobia can thrive and evolve.

Traditionally, research shows that media outlets and history textbooks in Turkey have contributed to shaping public perceptions of the Arabs through persistent stereotypes and negative portrayals reigned by the depiction of Arabs as traitors. However, the rise of digital platforms has transformed the landscape of public discourse, enabling more direct and widespread dissemination of hate speech. Online forums and social media sites, such as Ekşi Sözlük, have become pivotal in this shift, providing spaces where anti-Arab sentiments can be expressed, amplified, and normalized. Ekşi Sözlük, in particular, stands out as a significant platform due to its vast user base and influential role in shaping public opinion. The transition from traditional media to digital discourse has allowed for more nuanced and pervasive expressions of xenophobia, making online platforms critical arenas for the construction and reinforcement of hate speech against Arabs in Turkey.

This study aims to investigate the evolution and manifestation of anti-Arab prejudice in Turkey, focusing specifically on the digital platform Ekşi Sözlük. By analyzing user-generated content on Ekşi Sözlük, the research seeks to understand how hate speech against the Arab diaspora is constructed, disseminated, and perpetuated in the digital age. Through a mixed-method approach, this study will elucidate the role of digital platforms in sustaining and transforming xenophobic attitudes within Turkey’s socio-political landscape.

Research significance

This research seeks to provide an insight of the xenophobia and hate speech in the digital environment of Turkey through examining the scapegoating of an Arab community. Given the increasing role that social media plays as forums for the display of public expression, this study covers a definite gap in insight regarding how online habits reinforce racism, as well as animus towards a targeted ethnic group.

In the midst of these overlapping tensions, digital platforms serve as new arenas where entrenched biases, nationalist sentiments, and socio-political grievances converge and intensify. Rather than being neutral spaces, these online environments often act as accelerators, amplifying xenophobic commentary, sensationalized headlines, and one-dimensional portrayals of the Arab diaspora. The interplay between user-generated content, viral dissemination of hate speech, and limited accountability structures creates a fertile ground for the normalization and reinforcement of discriminatory narratives. Understanding how these online interactions shape, and are shaped by, underlying political and social pressures is essential to grasp the full spectrum of challenges facing the Arab diaspora in Turkey today.

While traditional media outlets – including printed newspapers, TV programs, and even radio shows – paved the way for negative and discriminatory narratives, digital platforms have emerged as potent enablers to reinforce them. The research highlights the need to appropriately contextualize the digital reproduction of hate speech through understanding the trajectory of anti-Arab hatred in Turkey.

Furthermore, this work contributes to the greater field of discourse on digital media and migration studies by offering a linguistic and thematic analysis of online discourse in this domain. Although much previous research has looked at how migrants are depicted in traditional media, there have been fewer studies about how digital platforms influence public attitudes as events happen. Therefore, in this respect, Ekşi Sözlük — as an example of participatory platforms — fulfills that role, contributing to the connection between media, digital racism, and xenophobia.

The research serves a policy purpose since its findings provide useful insight for the design of interventions to combat hate speech and foster social cohesion. This study, in identifying linguistic and discursive strategies invoked in targeting the Arab diaspora, offers practical takeaways for policymakers, educators, and digital platform administrators. The study highlights the importance of rigorous content moderation, inclusive dialogue, and educational efforts to counter xenophobic narratives and promote mutual understanding.

In conclusion, this study holds both academic importance and social relevance, being an attempt to better understand a critical problem by focusing on a country which has been recently experiencing a major transformation, not only in terms of its economy but also with regards to politics. This study's investigation of the reproduction of hate speech towards the Arab diaspora contributes to wider efforts at fighting xenophobia, protecting marginalized peoples, and fostering a just and integrated community in the digital age.

Research questions

The research is guided by the following key questions:

- How has anti-Arab sentiment evolved on Ekşi Sözlük from January 2021 to March 2024, and what trends can be identified in its expression?

- What linguistic and discursive strategies are employed on Ekşi Sözlük to perpetuate stereotypes and negative framing of the Arab diaspora?

- How do these digital discourses compare to traditional media representations in shaping public perceptions of Arabs in Turkey?

- Which socio-political, cultural, and historical factors influence the construction and dissemination of anti-Arab narratives in Turkey’s digital public sphere?

In responding to these questions, the study seeks to both reflect on and provide an overview of the complex relationship between media, migration and xenophobia as they play themselves out across digital platforms, potentially fostering negative public perceptions and stereotypes concerning particular communities. This research adds to recent conversations about the construction of hate speech on the web, highlighting the added challenge of merging historical hostility with newly perpetuated misinformation.

Research methodology

This study uses a mixed-method approach, combining web scraping with linguistic and textual analysis and thematic analysis to reveal the ways hate speech targeting the Arab diaspora is reproduced on Ekşi Sözlük. Trained on data until October 2024, this rich analytical framework guides an enlightening exploration into the linguistic, cultural, and ideological aspects of xenophobia within the realm of digital discourse. Through a grounded approach and by integrating qualitative and quantitative methods, this research provides in-depth and nuanced insights into the content while offering consistency across hierarchical levels of inquiry.

The first stage consisted of the web scraping process to build a strong dataset extracted from Ekşi Sözlük. A nonextensive computerized references of entries that included common keywords like "Arap" (Arab), "Araplar" (Arabs), and "Araplaşma" (Arabization) were retrieved using automated scraping tools. The dataset covers 3422 user-generated comments and texts from January 2021 to March 2024, thus providing a huge temporal coverage to analyze the trend in sentiments over time.

The second stage encompassed a corpus linguistic analysis, where the study examined precisely which expressions are used to describe Arabs on this platform, Ekşi Sözlük. This involved investigating word choices, sentence structures, and rhetorical devices that create and sustain stereotypes. This stage served to place these linguistic choices in context, revealing the implicit and explicit biases present in the discourse.

Using quantitative techniques like word frequency analysis helped reveal common words and patterns of association. For instance, high-frequency and emotive words (focusing on adjectives and adverbs) such as “işgalci,” meaning occupier, and “suç makinası,” meaning a "crime machine," are also flagged. Qualitative insights were achieved by exploring these terms in context to shed light on the stereotypes and narratives that circulate anti-Arab sentiment.

Finally, thematic analysis was used to identify and analyze broader themes within the data. Key themes were identified through coding, including hostility, security concerns, demographic fears, cultural tensions, and historical legacy. Beyond surface-level descriptions of the drivers of hate speech, this phase delved into the socio-political and cultural factors underpinning hate speech. Additionally, the findings were contextualized within historical and contemporary socio-political dynamics, such as perceptions of “Arabs as a security threat” and notions of “cultural incompatibility,” providing greater depth. While the thematic analysis of expressions of hate speech may reveal how hate is articulated, it also helps us understand why hate speech persists and evolves within digital spaces.

One of the key strengths of this methodology is its systematic progression from data collection to in-depth analysis, ensuring a comprehensive and representative dataset through web scraping while linguistic and textual analyses uncover the language and structure of hate speech. These findings are synthesized through thematic analysis, revealing overarching patterns and trends that offer deeper insights into the phenomenon. By integrating quantitative techniques, such as keyword counting, with qualitative approaches like context-driven interpretation and thematic categorization, the methodology provides both breadth and depth. It interlinks individual hate speech with broader societal and cultural dynamics, addressing its multifaceted nature from various perspectives. This mixed-method design aligns perfectly with the research goals, particularly the participatory features of Ekşi Sözlük, by enabling the study of both individual case studies and broader discursive trends, yielding findings that are granular yet comprehensive.

A historical overview of the Turkish-Arab Relations

Understanding the representation of the Arab diaspora in Turkey requires a foundational grasp of the historical and socio-political origins of anti-Arab sentiments and the broader dynamics of Turkish-Arab relations. Before delving into the analysis of contemporary discourse and representation, it is essential to explore how these deep-seated anti-Arab sentiments have been shaped over time. This background contextualizes the current themes of xenophobia, cultural tension, and public discourse and highlights the enduring legacy that influences modern perceptions and interactions.

Under the Ottoman Empire, Arabs and Turks were unified through shared cultural, religious, and political systems. However, the centralized administration of the empire during its later period created tensions, with policies perceived as neglectful or oppressive in Arab regions. These grievances laid the groundwork for Arab nationalism, fueled by the Young Turks' centralization efforts and perceived Turkification policies. This nationalist momentum culminated in the Arab Revolt of 1916, symbolizing a significant break from Ottoman control and fostering anti-Turkish sentiment among Arabs.

The collapse of the Ottoman Empire fragmented Turkish-Arab ties even more, leading to the emergence of the Turkish Republic and various independent Arab states. The post-Ottoman fragmentation redefined national identities and disrupted the shared bonds of the Ottoman era. The Kemalist era, marked by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk’s secular reforms and the abolition of the caliphate, deepened this divide.

The establishment of the Turkish Republic in the 1920s marked a dramatic shift from the legacy of the Ottoman Empire, driven by Atatürk's mission to modernize and westernize Turkey through strict secularist policies. These policies, mirroring the French model of militant laïcité, sought to separate religion from the state. This deliberate secularization coupled with the cultural or what is called letter reform (changing the Turkish Alphabet from Arabic script to Latin alphabet), created further distance between the Arabs and Turks, and relations with Middle Eastern countries were associated with a threat of potential return to the backwardness and darkness of the final eras of the Ottoman Empire, hindering the Turkish progress into the modern state framework. It is also critical to mention here that some Arabs also considered the Turks – who decided to embark into a modern statebuilding project – to have betrayed the caliphate and the union of the Ummah. Hence, a clear historical prejudgment and grievance was present on both sides.

Turkish media has historically perpetuated Anti-Arab narratives, often portraying Muslim-Arab religious identities negatively or omitting them altogether. This subtle form of Islamophobia contributed to the stigmatization of Arabs, who are frequently associated with Islamic symbols and practices. Military coups, particularly the 1997 "post-modern coup," further reinforced secularist ideologies by suppressing Islamist political parties such as the Welfare Party; this crackdown targeted not only Turkish Muslims but also indirectly affected Arabs in Turkey, fostering an environment of suspicion and exclusion toward Islamic identities.

Policies restricting religious expressions in educational institutions, such as bans on headscarves in universities, entrenched anti-Arab sentiments by associating Islamic practices with anti-modernity and resistance to integration. The convergence of media narratives and political turmoil solidified negative perceptions of Arabs in Turkish society.

In the modern era, Turkish-Arab relations have been shaped by regional and global dynamics. During the Cold War, Turkey's alignment with the West – joining NATO and establishing ties with Israel – contrasted sharply with the pan-Arab nationalist movements led by figures like Gamal Abdel Nasser. This divergence in political and ideological alignments deepened mistrust between Turkey and Arab nations.

A dramatic turn of events took place, however, in the last couple of decades with the rise of the Justice and Development Party (AKP), which marked a shift in Turkish-Arab relations. The AKP leveraged Turkey's historical and cultural connections with Arab nations to foster regional cooperation. Turkey, moreover, aimed to play a regional role especially after the Arab Spring, which has helped reshape the Turkish-Arab relationship and even enhanced the presence of the Arab diaspora in the country.

Turkish-Arab relations are the product of a complex interplay of historical, political, and cultural factors. The dissolution of the Ottoman Empire and the establishment of the Turkish Republic redefined Turkish national identity, distancing it from its Ottoman and Arab heritage. This historical shift, compounded by secularism and modernization efforts, laid the groundwork for tensions that persist in contemporary relations, despite increasing Turkish involvement in regional politics in the last decade.

Linguistic analysis and the collective perception of Arabs in Turkish digital discourse

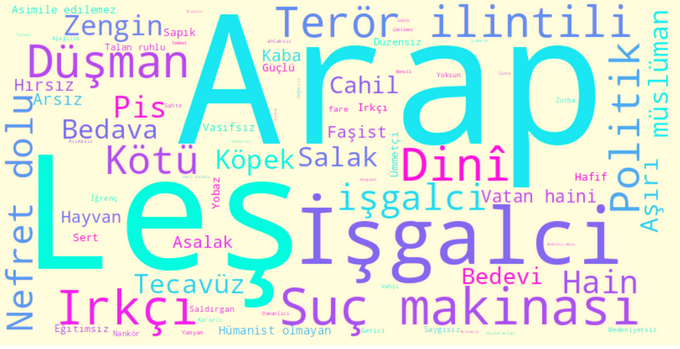

Figure 1: World Cloud and the frequently used words in describing Arabs and the Arab diaspora in Turkey

The linguistic analysis of anti-Arab language highlights the presence of xenophobic narratives, as revealed through Turkish social media. Examining key terms, particularly adjectives and adverbs, and their context, reveals an extensive use of hostile language, as illustrated in Figure 1. The word frequency analysis provides a quantitative view of these terms in socio-cultural contexts and offers a preliminary understanding of the stereotypical construction of Arabs and the Arab diaspora within the Turkish digital sphere, offering an immediate sense of the key themes in anti-Arab discourse.

The terminology used to describe Arabs reveals the underlying biases and collective attitudes of the Turkish digital sphere. The most commonly used adjectives describing Arabs are ‘Leş’ (Rotten), ‘Terör ilintili’ (Terror-linked), ‘Cahil’ (Ignorant), ‘Hain’ (Traitor), and ‘İşgalci’ (Occupier), which provide a sharp insight into these perspectives shaped by historical and socio-political grievances. Such terminology conjures images of Arabs as culturally inferior, politically opportunistic, or socially disruptive, characterizing them as “the other” in Turkish society. Adjectives such as “Suç Makinası” (Crime Machine) and “Terör ilintili” (Terror-linked) contribute to the perception of Arabs as inherently criminal and associated with terrorism, a stereotypical representation widely perpetuated in Western media.

Emotionally charged labels like “Nefret Dolu” (Full of Hate) and “Aşağılık” (Despicable) add visceral weight to anti-Arab rhetoric, amplifying xenophobic sentiments by evoking fear, disgust, and anger. These phrases contribute to framing Arabs as existential threats, fostering a groupthink mentality that validates exclusionary and discriminatory attitudes.

Cultural framing of Arabs is evident in terms like “Bedevi” (Bedouin), “Medeniyetsiz” (Uncivilized), and “Orta Çağ Kafalı” (Medieval-minded), which evoke notions of primitiveness and barbarism. These labels draw on historical and cultural stereotypes, portraying Arabs as less modern and inferior to the perceived progress of Turkish identity. On digital platforms, such terms are often used to create a class-based distinction between a "civilized" Turkish identity and an "uncivilized" Arab other. Indeed, the term “Bedevi” (Bedouin), while statistically significant, carries racist implications of cultural inferiority. Similarly, “Kültürsüz” (Uncultured) is frequently employed to reinforce a narrative of Arabs lacking culture, establishing a cultural hierarchy that elevates Turkish identity above that of Arabs.

A notable example is the frequent use of the adjective “İşgalci” (Occupier), which highlights the extent to which Arabs are scapegoated for economic and social challenges. This portrayal of Arabs as occupiers ties into a broader conspiracy theory suggesting a deliberate plan to "Arabize" Turkey and alter its demographic makeup. This narrative has been widely propagated in Turkish media and political discourse, particularly in the framing of Syrian and Afghan refugees as a demographic threat.

The specific references to “Hain” (Traitor) and “Vefasız” (Disloyal) link directly to the historical perception of Arabs as betrayers of the Turks, stemming from the Arab Revolts of 1916. Even after more than a century, this narrative of “Arabs as traitors” remains vivid and central to the construction of Arabs in the Turkish collective mindset. By revisiting historical discourses about Arabs, these representations serve as powerful tools for uncovering the frames and narratives that dominate and shape the collective perception of Arabs within Turkish digital spaces. Additionally the frequent presence of the term "İhanet" (Betrayal), referring to the politicization of anti-Arab sentiment draws upon historical narratives of Arab-Turkish relations oriented towards the Ottoman era. Their use evokes collective memories of perceived Arab treachery, rooted mistrust, and contemporary attitudes.

More infrequent terms, such as “Parazit” (Parasite), “Pis” (Dirty), “Çirkin” (Ugly), and “İğrenç” (Disgusting), construct a physiognomic perception of Arabs as inherently undesirable or repellent. These descriptors, though less common, carry significant weight in shaping negative stereotypes. By framing Arabs as "parasites," they evoke imagery of exploitation and unwelcome intrusion, aligning with deeply rooted xenophobic tropes. These terms do not merely describe physical attributes but symbolically dehumanize Arabs, reducing them to a social burden and justifying exclusionary attitudes. This rhetoric underscores a hostile perception that ties physical and moral characteristics to cultural incompatibility.

Terms such as "Uyumsuz" (Incompatible), "Entegre Edilmez" (Unintegrable), and "Geri Kafalı" (Backward-Minded) further reinforce this narrative, portraying Arabs as culturally and socially incompatible with Turkish society. This contributes to their marginalization and perpetuates the prejudice that common social cohesion and coexistence are impossible.

The language used in Turkish social media reflects the level of anti-Arab hatred existing in Turkish society and how ingrained it now is in the Turkish collective mind. Words with negative, emotionally charged, or culturally loaded meanings do more than reflect historical and socio-political tensions; indeed, they dynamically construct contemporary perceptions of Arabs as “the other.” Through an investigation of how often these terms are employed, the emotional depth they achieve, how they vary in sociopolitical status, and their active significance in the world as a set of cultural fables, this analysis makes a case for the role of language in producing stereotypes and leaving xenophobia unchallenged. Changing these damaging perceptions will take more critical engagement with digital platforms and a reframing of the narratives that shape public discourse.

Thematic analysis of Arabophobia: between stereotypes and misinformation

Drawing on thematic analysis, key patterns emerge, highlighting the persistent hostility toward Arabs, concerns over security and demographics, cultural tensions, and criticism of government policies. These themes not only reveal societal attitudes, but also underscore the role of digital spaces in amplifying divisive rhetoric. This explores these interconnected themes to argue that the negative portrayal of the Arab diaspora perpetuates xenophobic narratives, complicates integration, and reflects deeper socio-political challenges.

A striking aspect of the representation of Arabs in Turkey is the prevalence of hostility and derogatory language. Themes categorized as "Hostility and Insult" frequently depict Arabs in dehumanizing terms, with users expressing overt disdain for their presence in Turkey. This hostility is often articulated through direct insults, stereotypes, and scapegoating. Arabs are depicted as a monolithic group responsible for various societal ills, ranging from economic strain to cultural erosion. Such narratives are not just reflections of individual bias. but are indicative of entrenched xenophobic attitudes within segments of Turkish society. By normalizing derogatory language in public discourse, digital platforms contribute to the marginalization of the Arab diaspora, making hostility appear acceptable or even commonplace.

|

Theme |

Example Quote |

|

Historical Betrayal |

‘’Araplar; 1900 yıllarda anglo-saksonlarla işbirliği yaparak türk’ü arkadan hançerlemiş ve topraklarına onları yerleştirerek, güney bölgelerimizin işgaline yardım etmişlerdir.’’ ‘’Arabs; in the 1900s, collaborated with Anglo-Saxons to stab the Turks in the back, settled them on their lands, and aided the occupation of our southern regions.’’ |

|

Economic Exploitation |

‘’Evlerimizi satın alıp, bizi başka semtlere süren ırk. türk halkını kiraya bile çıkamaz hale getiren hükümetin bize birlikte attıkları kazığın adıdır.’’ ‘’They are the race that buys our houses and forces us to move to other neighborhoods. The government, together with them, has driven a stake into us, making it impossible for the Turkish people to even afford rent.’’ |

|

Arabs as Adversaries of Turks |

‘’Araplar, tarih boyunca türklerle daima çatışma halinde olmuşlardır. arap devletlerine göre. osmanlılar onları geri bırakılmışlar, sömürülmüşler ve soykırıma tabi tutulmuşlardır. okullarında bunlar okutuluyor. nesillerini bu şekilde yetiştiriyorlar. bakın bilen birisi olarak söylüyorum. arapların türklere duyulan nefret, nazilerin yahudilere duyduğu nefrete eşdeğerdir.’’ ‘’According to Arab states, the Ottomans left them underdeveloped, exploited them, and subjected them to genocide. These things are taught in their schools, and they raise their generations this way. Look, I’m speaking as someone who knows. The hatred Arabs feel toward Turks is equivalent to the hatred Nazis felt toward Jews.’’ |

|

Stereotypical Behavioral Criticism |

‘’Eliyle pilav yiyen, yüksek sesle konuşan invaziv insanlar.’’ "They are invasive people who eat rice with their hands and speak loudly." |

|

Cultural Incompatibility |

‘’Entegre edilemezler, gittikleri kültürü bozarlar. siz entegre olmak zorunda kalırsınız.’’ ‘’They cannot integrate; they disrupt the culture of the places they go. You are the one who has to integrate.’’ |

|

Cultural Imperialism and Religious Expansionism |

‘’Maalesef arapların kültür emperyalizmi islam ile çok güçlü. her islam yani müslüman olan biraz araplaşmak zorunda kalıyor, bu da arap milletinin yayılmasına olanak sağlıyor (...) sıra maalesef bu demografik işgal ile belki de türkiye'de’’ ‘’Unfortunately, the cultural imperialism of Arabs is very strong through Islam. Every Islam, that is, every Muslim, must Arabize to some extent, and this allows the Arab nation to expand. |

|

Arabs as Terrorists |

‘’Irak mesela yıllarca amerika tarafından seçilen tipler tarafından yönetilmiş, diktatörlüğün ve bitmeyen savaşların tadına doymuş en sonunda da fiilen parçalanmış ülke. fakirlik ve terörizm dışında dünyaya katkısı yoktur.’’ ‘’Iraq, for example, was governed for years by people chosen by America, was fed up with dictatorship and endless wars, and eventually practically fell apart. It has no contribution to the world other than poverty and terrorism.’’ |

Table 1: Thematic representation of Arabs and Arab Diaspora in Turkey

The main thematic representation of Arabs is organized based on the tropes and themes that emerged through the analysis, as exemplified in the table above through a selection of quotes from the corpus.

The historical betrayal theme reveals a quota of organizational narrative positioning Arabs as historically antagonists of Turks. One example, that Arabs cooperated with Anglo-Saxons in the early 1900s, suggests an image of betrayal where Arabs served as the helpers to the Anglo-Saxon loss of Turkish land and its sovereignty. These stories play on age-old grievances to further sow mistrust and animosity, presenting Arabs as fundamentally untrustworthy. This type of historical framing not only distorts collective memory, but also nurtures contemporary animosity, tying past conflicts to present tensions.

The narrative of Arabs as adversaries of Turks draws on historical hostilities and as a result presents an unbroken and static enmity. Accusations that Arab countries instill enmity toward Turks through education and cultural indoctrination, including comparisons to the pathological hatred that Nazis had for Jews, intensify such existential threats. This incendiary narrative allows for Arab dehumanization, reinforcing the idea of Arabs as forever foreign and incapable of peace. That is magnified in the digital plane, trivializing xenophobia and alienating the Arab diaspora even more.

A common trope is exploitation, framing Arabs as agents of economic upheaval and disparity. Takes about Arabs buying homes and kicking Turks out to worse neighborhoods play into wider fears of gentrification and rising living prices. Such portrayals serve to scapegoat Arabs for systemic economic difficulties, shifting the focus of blame away from structural problems and toward the mere presence of the Arab diaspora. This framing mounts economic resentment and compounds societal divisions by reiterating the idea that Arabs are a financial drain.

Another prevailing theme is stereotypical behavioral criticism, which utilizes cultural stereotypes to dehumanize and justify the exclusion of people identified as Arab. Referring to Arabs as “invasive people who eat rice with their hands and talk a lot” negates the diversity of their community and reduces it to broad and shallow generalizations. These stereotypes reinforce the idea of cultural essentialism and, by depicting Arabs as uncivilized, they fuel biases that hamper efforts at integration.

The story of cultural incompatibility builds on these stereotypes, depicting Arabs as fundamentally unable to assimilate into Turkish society: for example, the assertions that Arabs “disrupt the culture of the places they go” and compel others to adjust to them paints them as a cultural menace. This rhetoric not only divides the Arab diaspora, but also undermines multiculturalism itself; it implies that integration is a zero-sum game.

Fears of cultural and demographic change are fueled by narratives of cultural imperialism and religious expansionism, with the idea that Islam inherently “Arabizes” Muslims heightening anxieties about cultural assimilation. This perspective frames Arab influence as part of a continuum of imperialism, painting Arabs as aggressors in a cultural and religious war. Their presence is reframed as a “demographic invasion” that threatens Turkish identity, amplifying concerns about cultural preservation.

Related to this is the fear of demographic shifts tied to the Arab diaspora, concerns over high birth rates among Arabs and their potential to alter Turkey’s demographic composition echo anxieties about an invasive presence. This demographic argument intersects with fears about national identity, portraying Arabs as inherently incompatible with Turkish values and traditions and a threat to the Turkish future. Indeed, this thematic framing extends beyond social media; for instance, a short film that made headlines in Turkey depicted a dystopian future where Arabs remain in Turkey, become the majority, and transform the country into a dark, underdeveloped, and uncivilized place. Such rhetoric exacerbates societal divisions and provides a foundation for discriminatory policies aimed at restricting the permanence of Arabs in Turkey.

Another dominant trope is the normalization of Arabs as a security threat. This narrative correlates Arabs, especially refugees, with crime, terrorism and social unrest. Arabs have been branded, especially on Ekşi Sözlük, as a threat to Turkey’s national security, which is the ultimate label of “the other”: the dangerous element in society that corrupts both public and cultural order. Framing the duel in this way plays into wider fears about safety and stability, especially given Turkey’s political and economic woes.

Cultural tensions always play a starring role in the discourse, in everything from the language we use to how we eat to how we conduct our social lives made to seem incompatible. Instead of celebrating cultural diversity, these differences are exacerbated to represent Arabs as breads in the Turkish oven. Stripping away that diversity in order to fit Arabs into a preconceived narrative is itself a discriminatory act, and can lead to the creation of barriers to integration and mutual understanding through the propagation of stereotypes. Emphasizing on incompatibility, there is a wider challenge of creating a sense of coexistence with minimal prejudice in society.

Finally, a major thematic category that emphasizes stereotypical representation and anti-Arab sentiments is rooted in the criticism of government policies toward the Arab diaspora, particularly refugees. This criticism is deeply intertwined with hate speech against Arabs, making political opposition to AKP policies inherently connected to anti-Arab sentiments. Many comments express anger over the perception that the government prioritizes Arabs over Turkish citizens, often fueled by narratives of excessive generosity toward refugees. Skepticism about the government’s motives, such as the potential instrumentalization of aid policies for electoral gain, further amplifies public unrest. These criticisms exacerbate tensions between Turkish citizens and the Arab diaspora, frequently portraying Arabs as undeserving beneficiaries of the regime’s favoritism.

Indeed, as the presence of Arab migrants, refugees, and investors has grown, Arabs have increasingly been framed as scapegoats for economic difficulties, accused of siphoning national resources and contributing to local hardship. These contemporary pressures, when intertwined with historically established biases and deep-rooted narratives, reinforce the portrayal of Arabs as exploiters, disloyal accomplices, and catalysts of cultural deterioration. As such sentiments circulate and amplify online, they do more than merely echo traditional prejudices – they augment them with newly generated misinformation. In this way, digital discourse intensifies distrust and hostility, solidifying stereotypes through the continuous creation and propagation of misleading narratives that reshape public perceptions. Notably, these dynamics intensify during critical socio-political junctures, such as local elections and policy debates on immigration, when heightened public attention and political maneuvering catalyze the spread of these narratives. In these moments, anti-Arab rhetoric is not only more visible but also more volatile, becoming a potent tool to influence opinions, galvanize political support, and justify exclusionary measures.

Discussion and conclusion

Ekşi Sözlük plays a pivotal role in amplifying xenophobic narratives and shaping public discourse in Turkey. Its participatory and unregulated nature allows users to express extreme views anonymously, creating an environment conducive to the spread of hate speech. This pseudo-anonymity fosters the normalization of anti-Arab rhetoric, where grievances snowball into collective biases that reinforce societal divisions. Unlike traditional media, which operates under institutional constraints and editorial oversight, digital platforms like Ekşi Sözlük sustain continuous conversations that embed xenophobic attitudes into everyday discourse, making them pervasive and normalized.

Thematic patterns on the platform highlight recurring hostility, security fears, demographic anxieties, and cultural resentment toward Arabs. Terms like “işgalci” (occupier) and “suç makinası” (crime machine) portray Arabs as existential threats, while metaphors such as “demographic time bomb” amplify fears of cultural and demographic dissolution. This rhetoric relies heavily on generalizations and the homogenization of the Arab diaspora, framing them as a monolithic group responsible for societal ills like unemployment, inflation, and overcrowding. Such narratives are steeped in historical stereotypes and evoke tensions dating back to the Ottoman era, further rationalizing exclusion in contemporary Turkey.

This hostility is rooted in Turkey’s historical and political context. The Republic’s rupture with the previous Ottoman-Islamic identity fostered an ambivalent relationship with Arab culture, contributing to modern anxieties around “Arabization” and the perceived erosion of Turkish cultural uniqueness. The rise of nationalism, coupled with economic uncertainties, has further exacerbated anti-Arab animus, with political figures using anti-immigrant rhetoric to mobilize support and scapegoat Arabs, especially Syrian refugees, for economic and social challenges.

Ekşi Sözlük amplifies these narratives, creating echo chambers where hate speech flourishes without accountability. The platform provides an outlet for users to vent socio-political fears, reinforcing divisive attitudes that hinder social cohesion. The results of this study demonstrated a clear prevalence in anti-Arab sentiment over time that has both a historical background and is intensified by misinformation. This trend highlights how digital platforms are not merely reflections of societal biases, but active agents in shaping and perpetuating them.

To address these challenges, coordinated efforts are needed across government, media, and digital platforms to combat xenophobia. Policies targeting economic inequality and social insecurity must be paired with narratives that highlight the positive contributions of the Arab diaspora. Content moderation on digital platforms is essential to prevent the unchecked proliferation of hate speech. By fostering dialogue that emphasizes shared values and diversity, Turkey can begin to dismantle the historical, political, and digital factors that sustain anti-Arab sentiment in its online and offline spaces.