Use and Perception of Large Language Models in Arab Journalism Opportunities, Risks, and Epistemic Challenges

Executive Summary

This study examines how Arab journalists use, evaluate, and perceive large language models (LLMs) and generative AI tools within professional journalism, with particular attention to accuracy, bias, verification, and misinformation in politically sensitive and multilingual environments. Drawing on survey responses from 249 journalists based in Egypt, Morocco, Yemen, and Libya, the research provides one of the first systematic empirical accounts of LLM adoption in Arab journalism .

The findings show that generative AI tools are already deeply embedded in everyday journalistic workflows. A majority of respondents report frequent—often daily—use of LLMs for tasks such as background research, drafting, translation, summarization, and verification support. ChatGPT is the most widely used platform, followed by Gemini and other tools, with many journalists combining multiple models rather than relying on a single system. This pattern indicates that generative AI is no longer experimental or peripheral in Arab newsrooms, but infrastructural.

However, widespread adoption coexists with limited epistemic trust. Journalists consistently report significant flaws in LLM outputs, most notably hallucinations, outdated information, weak understanding of Arab political and economic contexts, limited handling of Arabic dialects, and perceived political or ideological bias. Hallucinations are the most frequently cited problem, and a substantial share of respondents consider these flaws serious or highly serious for their professional work. Trust in LLM outputs is therefore conditional and cautious, rather than automatic.

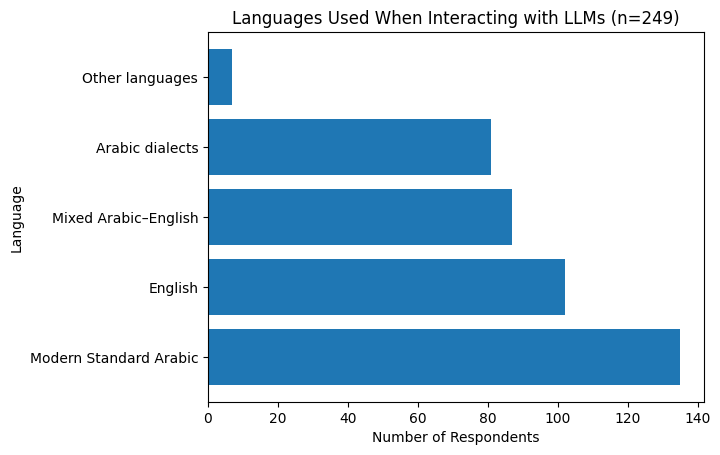

Language emerges as a key site of risk and adaptation. While Modern Standard Arabic is the most commonly used language when interacting with LLMs, many journalists deliberately switch to English—at least occasionally—to reduce errors and hallucinations. This practice reflects structural asymmetries in current AI systems, which remain optimized for English-language content. Evaluation of Arabic performance reveals moderate confidence at best: outputs are generally rated as average or good, but rarely as fully trustworthy, particularly for political and economic analysis.

Concerns about bias are especially pronounced when LLMs address sensitive regional issues such as the Palestinian cause, the war in Gaza, and other conflicts. A majority of respondents report observing clear or limited bias in such contexts, and only a small minority describe LLM outputs as accurate and trustworthy when explaining Arab political realities. These perceptions reinforce concerns that global AI systems may reproduce geopolitical and epistemic imbalances, particularly in the Global South.

At the same time, journalists express cautious optimism about the potential of LLMs to support verification and counter misinformation. Most respondents view LLMs as useful to some extent in verification work and believe they could play a positive role in countering misinformation, albeit under specific conditions. Crucially, this optimism is tempered by widespread recognition that the same tools could also contribute to the spread of misinformation or coordinated disinformation campaigns. Journalists therefore perceive LLMs as dual-use technologies, capable of both strengthening and undermining information integrity.

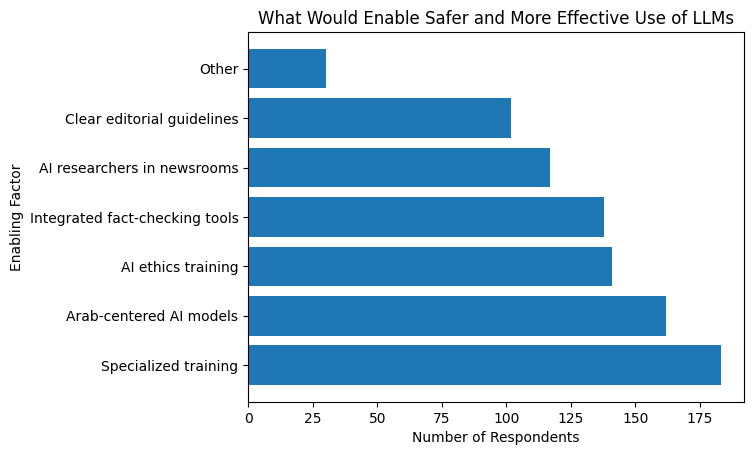

Levels of comfort in relying on LLMs are moderate rather than high. Most journalists describe themselves as only somewhat comfortable, reflecting a balance between practical reliance and professional caution. Importantly, respondents overwhelmingly emphasize institutional and structural solutions over individual adaptation. The strongest demands include specialized training, development of Arab-centered AI models, AI ethics education, integrated tools for fact-checkers, newsroom-level AI expertise, and clear editorial guidelines.

Overall, the study concludes that the central challenge is not whether Arab journalists will use LLMs—adoption is already widespread—but under what conditions these tools can be governed responsibly. Without context-aware, language-sensitive, and institutionally grounded frameworks, generative AI risks reinforcing epistemic inequality and information disorder. With such frameworks, it holds the potential to support more resilient, credible, and public-interest-oriented journalism in the Arab region.

Introduction

The rapid diffusion of large language models (LLMs) and generative artificial intelligence tools has begun to reshape journalistic practices worldwide. In the Arab region, where news production operates under conditions of political sensitivity, linguistic diversity, and high levels of information disorder, the adoption of these technologies presents both significant opportunities and substantial risks. Journalists increasingly rely on LLMs for tasks such as background research, verification support, drafting, translation, and contextual explanation. Yet the extent to which these tools are reliable, context-aware, and ethically usable in Arabic-language journalism remains insufficiently examined.

This research emerges from a growing concern among Arab journalists and media practitioners regarding the uneven performance of generative AI systems when dealing with Arabic content, regional political and economic contexts, and conflict-related issues. While global debates on AI and journalism often focus on newsrooms in the Global North, far less empirical attention has been paid to how these technologies function in non-English environments and politically constrained media ecosystems. The Arabic language itself, with its coexistence of Modern Standard Arabic, local dialects, and code-switching with English, poses structural challenges for LLMs largely trained on English-dominant datasets. These challenges are further compounded when journalists engage with sensitive topics such as the Palestinian cause, wars, regional conflicts, and authoritarian governance, where bias, omission, or hallucination can have serious professional and ethical consequences.

The problem this study addresses is therefore twofold. First, despite widespread and frequent use of LLMs among Arab journalists, there is a persistent gap between perceived usefulness and actual reliability, particularly in tasks related to verification, political analysis, and misinformation detection. Second, there is limited systematic evidence documenting journalists’ lived experiences with these tools, including the types of errors they encounter, how serious these errors are for their work, and the strategies they adopt to mitigate risks, such as switching languages or cross-checking outputs manually.

To address this gap, this study draws on a survey of 249 Arab journalists from different countries and media backgrounds. The survey captures patterns of usage, dominant platforms, linguistic practices, perceived flaws, observed biases, and levels of trust and comfort in relying on LLMs for journalistic tasks. It also explores journalists’ views on the dual role of generative AI as both a potential tool for countering misinformation and a possible vector for amplifying misleading narratives and coordinated disinformation campaigns.

The Arabi Facts Hub (AFH) 2024 Annual Report provides a comprehensive analysis of a structural "information disorder" in the MENA region, where restrictive legislation, systemic disinformation, and coordinated digital campaigns intersect to destabilize public discourse and violate digital rights. Based on a review of 5,402 monitored topics, the report reveals that 90% of fact-checked content was found to be false, including a notable rise in AI-generated items primarily focused on political conflicts such as the war in Gaza, Houthi naval operations, and regional economic crises. The report concludes that while regional governments misuse cybercrime and counterterrorism laws to criminalize legitimate digital expression, social media platforms, particularly X, have consistently failed to curb inauthentic behavior and hate speech, allowing harmful narratives to thrive unchecked. (Arabi Facts Hub, 2024).

The central research questions guiding this study are:

-

How frequently and for what purposes do Arab journalists use large language models in their professional work?

• Which LLM platforms are most commonly used, and how are they evaluated in terms of accuracy, contextual understanding, and language performance?

• What are the main technical, linguistic, and political flaws encountered by journalists when using generative AI, and how serious are these flaws for journalistic practice?

• To what extent do journalists perceive bias in LLM outputs when dealing with sensitive regional issues and conflicts?

• How do journalists assess the role of LLMs in verification and in countering, or potentially spreading, misinformation in the Arab region?

• What forms of institutional, technical, and ethical support do journalists identify as necessary for the safe and effective use of LLMs?

Based on these questions, the study pursues several interrelated goals. First, it aims to provide empirical evidence on how generative AI is currently used in Arab journalism, moving beyond speculative or anecdotal discussions. Second, it seeks to map the specific risks associated with LLM adoption in Arabic-language and politically sensitive reporting environments, with particular attention to hallucinations, outdated information, weak contextualization, and ideological bias. Third, the research aims to identify practical pathways for improving AI integration in journalism, as articulated by journalists themselves, including specialized training, clearer editorial guidelines, ethical frameworks, and the development of Arab-centered AI models and tools.

By grounding the analysis in the perspectives of journalists actively working in the field, this study contributes to broader debates on AI governance, media ethics, and information integrity in the Global South. It argues that the question is not whether Arab journalists will use LLMs, as adoption is already widespread, but under what conditions these tools can be made reliable, accountable, and genuinely supportive of public-interest journalism rather than a new source of epistemic risk.

Theoretical background

The integration of Large Language Models (LLMs) into professional domains, specifically Arab journalism, represents a significant technological shift that brings both transformative potential and profound epistemic risks. While generative AI is frequently framed as a tool for democratizing knowledge synthesis and improving efficiency, current research emphasizes a widening "productivity gap" and "linguistic disparity" between English-centric systems and the diverse cultural and linguistic realities of the Arab world (Koo, 2025; Al Rayes and Elnagar, 2025). This literature review examines the opportunities and challenges of LLM adoption in Arab journalism across four critical dimensions: linguistic complexity, trustworthiness and factuality, ideological alignment, and information governance.

Linguistic Disparities and the Productivity Gap

A foundational challenge identified in the literature is the structural and data-driven disadvantage faced by Arabic speakers when using global LLMs. Research by Koo (2025) demonstrates a significant cross-lingual effect on work quality, where AI-generated content in Arabic is rated lower in completeness, relevance, actionability, and creativity compared to English. This disparity is attributed to the scarcity of high-quality Arabic training data; while English typically accounts for over 90% of many multi-lingual corpora, Arabic often constitutes less than 1%.

Furthermore, the omission of diacritical marks in 97% of written Arabic text presents a unique morphological challenge for LLMs, frequently leading to disambiguation errors and nonsensical output. This results in a "productivity gap" where Arabic-speaking professionals, including journalists, benefit significantly less from AI assistance than their English-speaking counterparts, particularly in technical or creative domains.

Dialectal Complexity and Cultural Nuance

The Arab region is characterized by diglossia, where Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) coexists with various colloquial dialects. Literature suggests that while models like GPT-4 perform competently in formal or Classical Arabic (CA), they struggle to interpret the cultural background and metaphorical depth of regional dialects (Zibin et al, 2025).

In a comparative study of metaphor interpretation, Zibin et al. (2025) found that human participants from Jordan achieved a mean accuracy of 87.6% in interpreting colloquial metaphors, whereas AI tools achieved only 43.8%. While AI models demonstrated higher accuracy in interpreting formal CA metaphors compared to some human groups, they frequently failed in colloquial contexts—for example, misinterpreting the Lebanese or Jordanian expressions by defaulting to literal or nonsensical translations.

Conversely, some evidence suggests that LLMs can outperform traditional Neural Machine Translation (NMT) in preserving cultural nuances when handling authentic content, such as the Lebanese Arabic podcasts studied by Yakhni and Chehab (2025). This indicates that while linguistic barriers remain, LLMs possess a superior ability over previous architectures to handle culturally-rich datasets if properly aligned.

Trustworthiness, Verification, and Hallucination

For journalists, the truthfulness and safety of AI output are paramount. The AraTrust benchmark, introduced by Alghamdi et al. (2025), represents the first comprehensive evaluation of LLM trustworthiness in Arabic. Evaluating models across dimensions such as ethics, privacy, and illegal activities, the study found that GPT-4 was the most trustworthy, while prominent Arabic-centric models like Jais and AceGPT struggled to achieve even a 60% score.

The risk of "hallucination"—the confident generation of false assertions—remains a critical concern (Al Rayes and Elnagar, 2025). Research indicates that models face difficulties with fact-checking tasks due to inaccurate citation retrieval and a lack of domain-specific knowledge. As noted by Ma et al. (2026), current state-of-the-art models are "nearly unusable" for identifying sophisticated "deepfake" or rewritten misinformation in zero-shot settings, identifying human content as AI-generated at high rates.

Costello (2025) offers a more optimistic "World View," arguing that LLMs can democratize the synthesis of human knowledge by distilling expert evidence into human-friendly formats. However, he acknowledges that AI trained on biased data can propagate bias at scale, requiring journalists to remain vigilant against plausible-sounding but incorrect information.

Ideological Alignment and Creator Worldviews

LLMs are not neutral; they act as gatekeepers of information that reflect the ideological stances of their creators. Buyl et al. (2026) conducted a large-scale analysis of 19 LLMs, revealing sharp disparities in ideological positions across geopolitical regions. Their findings indicate that Arabic-oriented models like Jais and Silma occupy distinct ideological positions, often leaning toward free-market advocates and national priorities, whereas Western models align more closely with progressive pluralism.

This creates a risk of political instrumentalization, where the choice of a specific LLM can shift the "ideological center of gravity" of journalistic content. Keleg (2025) further critiques the common assumption of a homogenous Arab culture in LLM alignment, arguing that assuming a single cultural framework neglects the internal diversity of the region and risks flattening local nuances into a generic "Arab" output.

Information Governance and Mis/Disinformation

The use of LLMs in generating and detecting misinformation presents a major challenge for information governance. Ma et al. (2026) identified a "quality modulation effect" in AI-generated content: as the quality of AI text increases, it becomes over-standardized and loses individuality. This makes high-quality AI misinformation harder for both humans and AI-based detectors to distinguish from authentic text, as it mimics formal, academic, or professional registers.

Despite these risks, there is a global movement toward "Sovereign AI," where nations in the Global South seek to build their own models to reflect local social, cultural, and economic realities (Burgos, 2025). The UAE’s Falcon family and projects like AraBERT are part of a strategic effort to reduce dependence on US or Chinese infrastructure and prevent "digital language death". Small, adapter-tuned models are increasingly seen as a sustainable path for public-sector deployments that require local accountability and cultural sensitivity.

Methodological Limitations in Evaluation

The current landscape of Arabic LLM evaluation is hampered by methodological gaps. Al Rayes and Elnagar (2025) point out that most existing benchmarks rely heavily on Multiple-Choice Questions (MCQs), which may inflate performance through guessing and fail to assess deep generative capabilities. There is a pronounced absence of separate intrinsic evaluations (linguistic understanding) and extrinsic evaluations (task-based performance in real-world contexts like journalism). Furthermore, benchmarks are often confined to Modern Standard Arabic, leaving the dialectal variety used by the majority of the population under-evaluated.

The literature suggests that while LLMs offer Arab journalists unprecedented tools for knowledge synthesis and content generation, their current state is marred by epistemic challenges and linguistic inequality. The "productivity gap" identified by Koo (2025) and the trustworthiness limitations noted by Alghamdi et al. (2025) suggest that LLMs should be treated as assistive rather than authoritative tools.

To mitigate these risks, the research emphasizes the need for:

- More language-inclusive and culturally-aligned benchmarks that move beyond MCQs to evaluate reasoning and cultural nuance (Al Rayes and Elnagar, 2025).

- Increased transparency regarding the ideological design choices that engrain creator worldviews into model behavior (Buyl et al, 2026).

- The development of "Sovereign AI" and Arab-centered models that can handle the region's linguistic diversity and prevent digital language death (Burgos, 2025).

- Specialized training for journalists to identify AI-generated misinformation that has been "polished" to appear human-like (Ma et al, 2026).

Ultimately, the responsible integration of generative AI in Arab journalism requires a context-aware approach that rejects the assumption of cultural homogeneity and prioritizes veracity, transparency, and regional linguistic sovereignty.

Methodology

Research design

This study adopts a quantitative, descriptive research design based on a structured survey administered to professional journalists working in the Arab region. The objective of the methodology is to systematically capture journalists’ patterns of use, perceptions, and evaluations of large language models (LLMs) in journalistic practice, particularly in relation to accuracy, bias, verification, and misinformation. A survey approach was selected as the most appropriate method to document lived professional experiences at scale, allowing for comparative analysis across multiple dimensions of use, language, and perceived risk.

Sample and participants

The study draws on responses from 249 Arab journalists based in four countries: Egypt (113 respondents), Morocco (57), Yemen (47), and Libya (32). Participants were recruited through professional media networks, journalist associations, and digital communication channels commonly used by journalists in the region. Eligibility criteria required respondents to be actively engaged in journalistic or editorial work and to have at least some professional exposure to generative AI tools.

The sample includes journalists working across a range of media formats, including digital news platforms, print media, broadcast outlets, and fact-checking organizations. While the survey does not claim statistical representativeness of all Arab journalists, it captures a diverse cross-section of practitioners operating in politically sensitive, multilingual, and high-risk information environments. This geographic and professional diversity is central to the study’s analytical focus.

Data collection

Data were collected through an online questionnaire distributed over a defined data-collection period. The questionnaire was designed to be concise, accessible, and suitable for mobile and desktop completion, in order to maximize participation among working journalists. Participation was voluntary, and responses were collected anonymously to encourage candid assessment of AI tools without professional or institutional pressure.

The survey consisted of closed-ended questions using multiple-choice and ordinal response formats. This design enabled respondents to evaluate frequency of use, perceived seriousness of flaws, and levels of trust and comfort in a standardized manner, facilitating comparative analysis across variables.

Survey instrument

The questionnaire was structured around four main thematic clusters:

- Patterns of use and platforms

Questions in this section assessed which LLMs journalists use, how frequently they rely on generative AI in their work, and the primary languages used when interacting with these tools.

- Accuracy, flaws, and performance

This cluster focused on identifying the main technical and epistemic problems encountered when using LLMs, including hallucinations, outdated information, weak contextual understanding of Arab political and economic issues, linguistic limitations, and ideological or political bias. Respondents were also asked to evaluate how serious these flaws are for their journalistic work and to assess LLM performance specifically when operating in Arabic.

- Bias, misinformation, and verification

This section examined journalists’ observations of bias in LLM outputs when addressing sensitive issues such as the Palestinian cause, war in Gaza, and regional conflicts. It also explored perceptions of LLMs’ usefulness in verification processes and their potential dual role in both countering and contributing to misinformation and coordinated disinformation campaigns.

- Trust, comfort, and institutional needs

The final cluster measured journalists’ comfort levels in depending on LLMs in their professional work and identified the types of support they believe are necessary for safe and effective use. These included specialized training, AI ethics education, development of Arab-centered models, integration of AI researchers within newsrooms, fact-checking tools, and clear editorial guidelines.

Data analysis

Survey responses were analyzed using descriptive statistical methods. Frequencies and distributions were calculated for each question to identify dominant trends, shared concerns, and points of divergence among respondents. Given the exploratory and descriptive nature of the study, the analysis focuses on patterns of perception and practice rather than causal inference.

The results are presented in aggregated form to highlight structural issues affecting AI use in Arab journalism, rather than individual behaviors. Where relevant, comparisons are drawn between different levels of usage frequency, language practices, and perceived seriousness of flaws.

Ethical considerations

The study adhered to basic ethical research standards. Participation was voluntary, no personally identifiable information was collected, and respondents could exit the survey at any time. The research did not involve vulnerable populations, nor did it request sensitive personal data. Given the political sensitivity of journalism in the Arab region, anonymity was treated as a core ethical safeguard.

Limitations

Several limitations should be noted. First, the sample is not statistically representative of all journalists in the Arab region, and findings should be interpreted as indicative rather than generalizable. Second, the study relies on self-reported perceptions, which may be influenced by individual experience, familiarity with AI tools, or professional role. Third, the survey captures a snapshot in time within a rapidly evolving technological landscape; perceptions and practices may shift as LLMs develop and newsroom policies evolve.

Despite these limitations, the methodology provides robust empirical insight into how generative AI is currently understood and used by Arab journalists, offering a valuable foundation for future longitudinal, qualitative, and comparative research.

Results

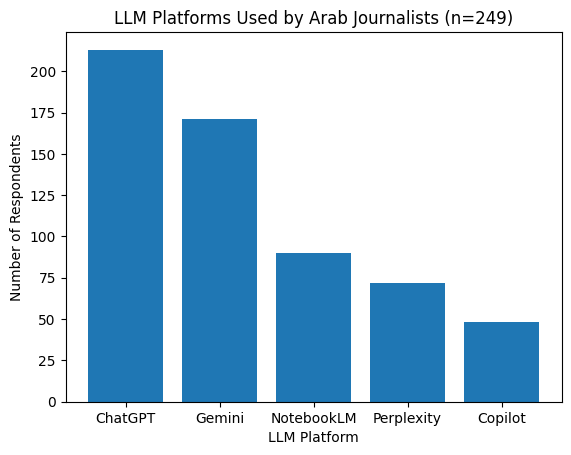

The findings indicate widespread adoption of LLMs among Arab journalists. ChatGPT is the most commonly used platform, reported by 213 respondents, followed by Gemini (171), Google NotebookLM (90), Perplexity (72), and Copilot (48). Many respondents reported using more than one model, suggesting that journalists often combine tools rather than relying on a single platform.

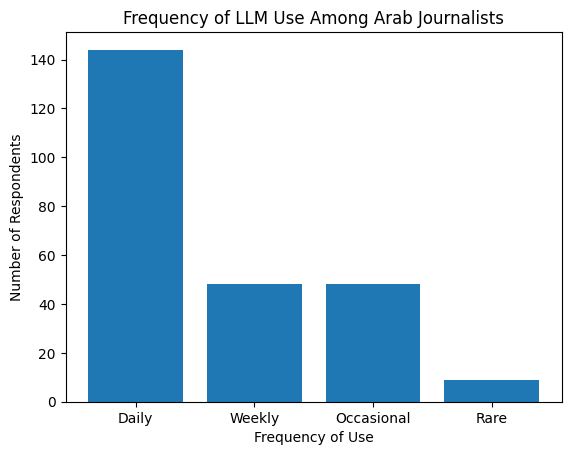

In terms of frequency of use, reliance on generative AI is high. A majority of respondents reported daily use (144), while others indicated weekly use (48) or occasional use (48). Only a small number of journalists reported rare use (9). These results suggest that LLMs have become embedded in everyday journalistic workflows rather than being experimental or marginal tools.

Perceived flaws and limitations of LLMs

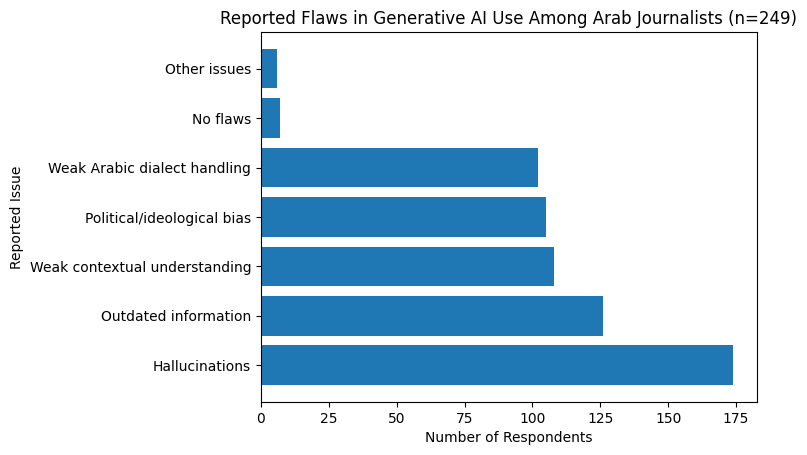

Respondents identified several recurring flaws when using generative AI. Hallucinations were the most frequently reported issue, cited by 174 journalists. Outdated or insufficiently updated information was reported by 126 respondents, while weak understanding of Arab political and economic contexts was noted by 108 respondents. Perceived political or ideological bias was reported by 105 journalists, and weak handling of Arabic dialects by 102. Only a small number of respondents reported encountering no flaws (7) or other unspecified issues (6).

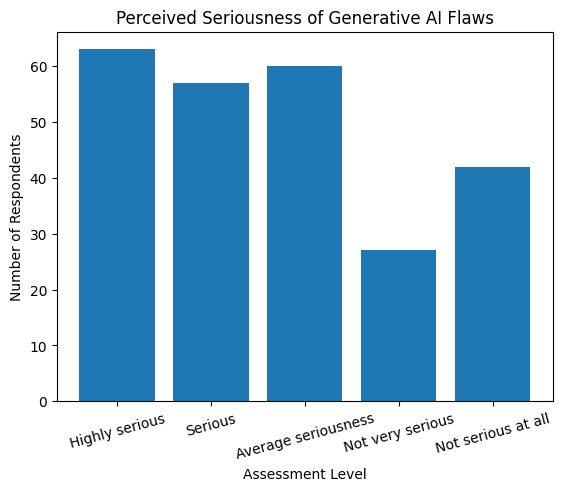

When asked to assess how serious these flaws are for their work, responses were divided. Sixty-three journalists described the flaws as highly serious, and 57 as serious. Sixty respondents considered the flaws to be of average seriousness, while 27 described them as not very serious. Forty-two respondents indicated that the flaws were not serious at all. These findings point to a significant level of concern regarding reliability, even among frequent users of LLMs.

Language use and accuracy in Arabic

Journalists reported using multiple languages when interacting with LLMs. Modern Standard Arabic was the most commonly used language (135), followed by English (102). A substantial number of respondents reported mixing Arabic and English (87), while 81 indicated using Arabic dialects. A small number reported using other languages (7).

When asked whether they use English to mitigate hallucinations or mistakes, most respondents indicated doing so at least occasionally. One hundred thirty-five respondents reported sometimes using English for this purpose, while 39 responded “yes, clearly,” and 9 “yes.” Sixty respondents reported not using English for mitigation, and 6 indicated uncertainty. This suggests that language switching is a common risk-management strategy among journalists.

Evaluation of LLM accuracy when using Arabic revealed moderate confidence levels. One hundred eight respondents rated accuracy as average, 84 as good, and 24 as excellent. Eighteen respondents described accuracy as weak, and 3 as very weak, while 12 indicated that they were unsure. Overall, the findings suggest that while Arabic performance is not perceived as entirely unreliable, it is rarely viewed as fully trustworthy.

Bias and sensitive political issues

A substantial number of respondents reported observing bias in LLM outputs when dealing with sensitive regional issues, including the Palestinian cause, the war in Gaza, and other conflicts. One hundred five journalists reported clear bias, while 72 reported limited bias. Thirty-nine respondents reported observing no bias, and 33 indicated uncertainty.

Evaluation of LLM performance in explaining and analyzing political and economic issues in the Arab region further reflected these concerns. Only 21 respondents described the performance as accurate and trustworthy. Ninety-three considered it good but with defects, while 84 described it as average and lacking contextual depth. Thirty-six respondents evaluated performance as weak and misleading, and 5 selected other assessments.

LLMs, verification, and misinformation

When asked to evaluate the benefits of LLMs in verification work, the majority of respondents expressed cautious optimism. Fifty-four described LLMs as highly useful, and 138 as useful to some extent. Thirty-three respondents reported neutral views, while 9 described LLMs as useless, and 15 as harmful or risky.

Regarding the potential role of LLMs in countering misinformation in the Arab region, 102 respondents expressed strong belief in their positive role, while 81 believed this potential exists but only under certain conditions. Eighteen respondents believed the contribution would be limited, 6 rejected the idea, and 42 were unsure.

At the same time, respondents also expressed concern that LLMs could contribute to the spread of misinformation or coordinated disinformation campaigns. Sixty-six journalists believed this could occur greatly, while 123 believed it could occur within limits. Eighteen believed this risk was weak, 6 rejected it, and 36 were uncertain. These findings underscore journalists’ perception of LLMs as dual-use technologies.

Trust and comfort in journalistic reliance on LLMs

Levels of comfort in relying on LLMs varied. Forty-five respondents reported being very comfortable, while 117 reported being comfortable to some extent. Sixty-three respondents expressed neutral positions. Twenty-one respondents reported being concerned, and 3 reported being highly concerned.

When asked about what would enable safer and more effective use of LLMs, respondents emphasized institutional and structural solutions rather than individual adaptation. Specialized training was selected by 183 respondents, followed by the development of Arab-centered AI models (162), AI ethics training (141), integrated tools for fact-checkers (138), integration of AI researchers within media outlets (117), and clear editorial guidelines (102). Other suggestions were provided by 30 respondents.

Key Findings

- Generative AI is already embedded in everyday journalistic work

Large language models are no longer experimental tools in Arab journalism. Most surveyed journalists use LLMs frequently, often on a daily basis, indicating that generative AI has become part of routine newsroom workflows rather than an optional or peripheral technology.

- High adoption coexists with limited epistemic trust

Despite widespread use, journalists express only moderate confidence in LLM accuracy, particularly when working in Arabic or addressing political and economic issues in the Arab region. Trust in LLM outputs is conditional and cautious, rather than comprehensive or automatic.

- Hallucinations and outdated information are the dominant risks

Hallucinations are the most frequently reported flaw, followed by the use of outdated or insufficiently updated information. A significant share of journalists consider these flaws serious or highly serious for their professional work, especially in verification and political reporting.

- Weak contextual understanding of the Arab region remains a core limitation

Journalists consistently report that LLMs struggle to accurately explain or analyze Arab political, economic, and social contexts. Outputs are often perceived as generic, shallow, or detached from regional realities, limiting their usefulness for in-depth journalism.

- Arabic language performance is functional but not fully reliable

While LLMs can operate in Modern Standard Arabic, their performance is generally evaluated as average rather than trustworthy. Handling of Arabic dialects remains particularly weak, reinforcing linguistic inequities in AI-supported journalism.

- Language switching to English is a common risk-mitigation strategy

Many journalists deliberately switch to English when interacting with LLMs to reduce hallucinations and factual errors. This practice reflects both user adaptation and structural bias in current AI systems toward English-language content.

- Perceived political and ideological bias is widespread

A majority of respondents report observing clear or limited bias in LLM outputs when addressing sensitive issues such as the Palestinian cause, the war in Gaza, and regional conflicts. These perceptions raise concerns about neutrality, framing, and geopolitical asymmetries in AI systems.

- LLMs are viewed as dual-use technologies in the misinformation ecosystem

Journalists believe LLMs can support verification and counter misinformation, but they also recognize their capacity to generate or amplify misleading narratives and coordinated disinformation campaigns. This dual-use perception shapes cautious and conditional reliance.

- Comfort with LLM reliance is moderate and uneven

Most journalists describe themselves as only somewhat comfortable relying on LLMs in their work. A smaller group expresses concern, indicating persistent uncertainty about professional, ethical, and reputational risks.

- Journalists prioritize institutional solutions over individual coping

Respondents overwhelmingly emphasize the need for specialized training, ethical guidance, Arab-centered AI models, integrated fact-checking tools, and newsroom-level governance frameworks. Individual skill is seen as insufficient without institutional support.

Discussion

The findings of this study reveal a complex and ambivalent relationship between Arab journalists and large language models (LLMs). On the one hand, generative AI tools have been rapidly and deeply integrated into journalistic workflows, with daily use reported by a majority of respondents. On the other hand, this high level of adoption coexists with persistent skepticism regarding accuracy, contextual understanding, and political neutrality. This tension between practical reliance and epistemic distrust is the central empirical insight of the study.

1. Widespread use under conditions of limited trust

The high frequency of LLM use suggests that these tools are no longer peripheral or experimental within Arab journalism. Instead, they function as infrastructural technologies that support routine tasks such as research, drafting, summarization, and verification support. However, the fact that most respondents rated LLM performance in Arabic and in political analysis as only average or conditionally reliable indicates that usage is driven less by confidence in epistemic authority and more by pragmatic necessity. In contexts marked by time pressure, resource constraints, and shrinking newsrooms, journalists appear willing to tolerate known flaws in exchange for efficiency gains, while maintaining a degree of professional caution.

This pattern aligns with broader findings in journalism studies suggesting that technological adoption often precedes the development of institutional norms, ethical frameworks, and shared standards of evaluation. In the Arab region, this gap is further widened by the political sensitivity of reporting environments, where errors, misframings, or biased interpretations can have serious professional and personal consequences.

2. Language, context, and epistemic asymmetry

The findings highlight language as a key site of epistemic vulnerability. While Modern Standard Arabic is widely used, journalists frequently resort to English—at least intermittently—to mitigate hallucinations and inaccuracies. This practice reflects an implicit recognition of the English-centric training and optimization of current LLMs. Rather than being a neutral choice, language switching functions as a risk-management strategy, revealing structural asymmetries in how AI systems handle knowledge production across languages.

The relatively low confidence in LLM performance when explaining Arab political and economic issues further underscores the limits of these systems’ contextual understanding. Weak engagement with local political economies, historical trajectories, and power relations suggests that LLM outputs often flatten complexity or reproduce generalized narratives detached from regional realities. For journalists working in politically dense environments, such contextlessness is not a minor technical flaw but an epistemic limitation with direct implications for accuracy and credibility.

3. Bias and the politics of generative AI

Perceptions of political and ideological bias, particularly in relation to the Palestinian cause, the war in Gaza, and regional conflicts, constitute one of the most significant findings of the study. The high number of respondents reporting clear or limited bias suggests that concerns about neutrality are not marginal but widely shared. These perceptions resonate with existing critiques of generative AI systems as products of specific geopolitical, institutional, and corporate contexts, in which training data, content moderation policies, and safety guardrails are unevenly aligned with Global South perspectives.

Importantly, the findings do not suggest a simple rejection of LLMs on political grounds. Rather, journalists appear to engage with these tools critically, aware of their positionality and limitations. This critical engagement reflects a form of professional epistemic vigilance, in which outputs are treated as provisional and contestable rather than authoritative. Such vigilance, however, depends heavily on individual skill and experience, raising questions about uneven risk exposure across newsrooms and career stages.

4. Verification, misinformation, and the dual-use dilemma

One of the most striking aspects of the findings is the dual perception of LLMs as both tools for countering misinformation and potential amplifiers of misleading narratives. Journalists largely believe that LLMs can support verification work, but rarely without conditions. At the same time, a significant majority acknowledge the risk that these systems could contribute to misinformation or coordinated disinformation campaigns, whether through hallucinations, biased framing, or automated content generation at scale.

This dual-use dilemma reflects a broader structural contradiction in generative AI: the same capabilities that make LLMs useful for summarization, pattern recognition, and rapid analysis also make them powerful instruments for narrative manipulation. In the Arab region, where information ecosystems are already saturated with propaganda, state-aligned media, and coordinated influence operations, the uncritical deployment of LLMs risks compounding existing vulnerabilities.

5. Institutional needs and the limits of individual adaptation

The strong emphasis placed by respondents on specialized training, ethical frameworks, Arab-centered models, and newsroom-level integration of AI expertise suggests a clear recognition that individual coping strategies are insufficient. Journalists do not view safe AI use as a matter of personal responsibility alone, but as a collective and institutional challenge requiring organizational investment and governance.

Notably, the demand for developing Arab-centered AI models points to a deeper critique of the current AI landscape. Rather than merely calling for better tools, journalists are implicitly challenging the structural marginalization of Arabic language and regional knowledge within global AI development. This demand aligns with emerging debates on AI sovereignty, linguistic justice, and the need for regionally grounded AI ecosystems.

Implications

The findings of this study have important implications for journalistic practice, newsroom governance, AI development, and media policy in the Arab region. They demonstrate that generative AI is already embedded in journalistic work, but that its integration remains largely informal, uneven, and weakly governed. Addressing this gap requires coordinated action across professional, institutional, and technological levels.

1. Implications for journalists and newsrooms

For journalists, the results underscore the need to approach LLMs as assistive tools rather than authoritative sources of knowledge. High levels of reported hallucination, contextual weakness, and perceived bias indicate that outputs require systematic verification and editorial oversight, particularly when dealing with political, economic, and conflict-related topics. Reliance on individual judgment alone is insufficient, especially in fast-paced news environments where time pressures can incentivize uncritical use.

For newsrooms, the findings point to the urgency of institutionalizing AI use through clear editorial policies and workflows. Editorial guidelines should define acceptable and unacceptable uses of generative AI, establish verification requirements, and clarify accountability for AI-assisted content. Without such frameworks, AI use risks becoming ad hoc and uneven, exposing journalists and organizations to ethical, reputational, and legal risks.

2. Implications for training and professional development

The strong demand for specialized training and AI ethics education highlights a critical capacity gap. Training programs should move beyond basic tool literacy and focus on risk-aware use, including detecting hallucinations, identifying bias, understanding model limitations, and integrating AI outputs into verification processes responsibly. Such training should be continuous rather than one-off, reflecting the rapid evolution of AI systems.

Importantly, training should be tailored to the linguistic and political realities of the Arab region. Generic AI training developed for English-language newsrooms is unlikely to address challenges related to Arabic dialects, code-switching, or region-specific political sensitivities. Embedding AI literacy within existing journalistic ethics frameworks may help align technological competence with professional norms.

3. Implications for AI developers and platform governance

The findings carry clear implications for AI developers and companies deploying LLMs in Arabic-speaking markets. Weak contextual understanding, limited dialect handling, and perceived political bias suggest that current models insufficiently represent Arab knowledge systems, histories, and perspectives. Improving performance requires not only expanding Arabic-language datasets, but also addressing how regional content is curated, weighted, and moderated.

From a governance perspective, greater transparency is needed regarding training data, content moderation policies, and bias mitigation strategies, particularly in relation to conflict and geopolitics. Without such transparency, journalists are left to infer bias empirically, which undermines trust and limits responsible adoption.

4. Implications for verification and misinformation ecosystems

The dual perception of LLMs as tools for verification and as potential misinformation vectors has direct implications for fact-checking organizations and information integrity initiatives. Integrating LLMs into verification workflows should prioritize human-in-the-loop systems, where AI supports but does not replace professional judgment. Automated or semi-automated verification tools must be designed with safeguards that prevent the amplification of false or misleading narratives.

At the ecosystem level, funders and media development organizations should support the development of AI-assisted verification tools specifically adapted to Arabic-language misinformation patterns, rather than importing tools optimized for other contexts. This includes attention to dialectal misinformation, visual narratives, and region-specific propaganda techniques.

5. Implications for policy and AI governance in the Global South

The findings contribute to broader debates on AI governance in the Global South. They illustrate how global AI systems, when deployed without regional adaptation, can reproduce epistemic inequalities by privileging certain languages, narratives, and political framings. Policymakers and regulators should therefore consider journalism as a high-risk domain for AI deployment, particularly in conflict-affected and politically constrained environments.

Supporting the development of Arab-centered AI models, research partnerships between media organizations and AI researchers, and regional governance frameworks can help mitigate these risks. Such measures would not only enhance journalistic practice, but also strengthen public trust and democratic discourse in the Arab region.

Recommendations

Based on the findings of this study, a set of interrelated recommendations is proposed to support the responsible, effective, and context-aware integration of large language models (LLMs) into journalistic practice in the Arab region. These recommendations address journalists and newsrooms, media development actors, AI developers, and policymakers.

1. Institutionalize AI use through newsroom governance frameworks

Media organizations should develop and adopt clear editorial guidelines governing the use of generative AI. These frameworks should define acceptable and prohibited uses of LLMs, establish mandatory verification and attribution standards for AI-assisted content, and clarify editorial accountability. Special safeguards should be applied to political, economic, and conflict-related reporting, where the risks of hallucination and bias are highest.

2. Invest in continuous, specialized training for journalists

Journalists require training that goes beyond basic AI literacy. Media organizations, journalism schools, and funders should support continuous professional development focused on:

– identifying hallucinations and factual errors,

– recognizing political and ideological bias in AI outputs,

– responsible use of AI in verification and fact-checking,

– managing linguistic risks in Arabic and its dialects.

Training should be region-specific and embedded within journalistic ethics education.

3. Treat AI-assisted verification as a human-in-the-loop process

LLMs should be integrated into verification workflows only as assistive tools, not as automated decision-makers. Fact-checking processes should require human oversight at every stage, with clear protocols for cross-checking AI outputs against primary sources. This approach reduces the risk of amplifying false or misleading information.

4. Support the development of Arab-centered AI models and tools

Governments, research institutions, donors, and AI developers should invest in the development of Arabic-language and dialect-aware AI models, as well as tools designed specifically for Arab media ecosystems. This includes support for open datasets, regional research collaborations, and transparent evaluation benchmarks that reflect Arab political, social, and linguistic realities.

5. Strengthen transparency and accountability of AI providers

AI companies deploying LLMs in Arabic-speaking markets should increase transparency regarding training data, bias mitigation strategies, and content moderation policies related to geopolitical and conflict-related topics. Greater transparency is essential for journalists to assess the reliability and limitations of AI tools used in their work.

6. Integrate AI expertise within media organizations

Media outlets should consider integrating AI researchers or data specialists into editorial teams to support responsible adoption, tool evaluation, and internal capacity-building. This can help bridge the gap between technical development and journalistic practice, reducing reliance on informal individual strategies.

7. Recognize journalism as a high-risk domain in AI governance

Policymakers and regulators should explicitly recognize journalistic use of LLMs as a high-risk application, particularly in politically sensitive and conflict-affected contexts. AI governance frameworks should include specific provisions addressing media integrity, editorial independence, and protection against automated disinformation.

8. Encourage regional and cross-sector collaboration

Regional cooperation between journalists, fact-checkers, researchers, civil society organizations, and AI developers should be strengthened to share knowledge, develop standards, and collectively address risks. Such collaboration can help counter fragmentation and promote shared norms for responsible AI use in Arab journalism.

Conclusion

This study set out to examine how Arab journalists are engaging with large language models and generative AI tools at a moment when these technologies are rapidly reshaping journalistic practice but remain weakly governed. Drawing on survey data from 249 journalists across the Arab region, the paper provides empirical insight into patterns of use, perceived benefits, identified risks, and the conditions under which LLMs are considered acceptable or problematic in professional journalism.

The findings demonstrate that generative AI is no longer a peripheral or experimental technology in Arab newsrooms. Journalists use LLMs frequently, often on a daily basis, integrating them into core tasks such as research, drafting, contextual explanation, and verification support. However, widespread adoption has not translated into high levels of epistemic trust. Hallucinations, outdated information, weak contextual understanding of Arab political and economic realities, linguistic limitations, and perceived political bias remain central concerns. These issues are particularly acute when journalists engage with sensitive topics such as regional conflicts, the Palestinian cause, and questions of power and governance.

A central conclusion of the study is that Arab journalists relate to LLMs through a mode of cautious pragmatism. They recognize the efficiency and practical value of generative AI, while simultaneously developing informal strategies to manage its risks, including language switching, intensive cross-checking, and selective reliance. This mode of use reflects professional vigilance rather than uncritical adoption, but it also exposes the limits of individual adaptation in the absence of institutional safeguards.

The study further highlights the dual nature of LLMs in relation to misinformation. Journalists view these systems as potentially valuable tools for verification and countering false narratives, yet they are equally aware of their capacity to generate, amplify, or legitimize misleading content at scale. This dual-use character underscores the need to treat generative AI as a high-impact technology within journalism, particularly in information environments already marked by political pressure and disinformation.

Ultimately, the paper argues that the key challenge is not whether generative AI will be used in Arab journalism, but how it will be governed. The strong demand expressed by journalists for specialized training, ethical frameworks, Arab-centered AI models, and newsroom-level governance points to a clear path forward. Responsible integration requires shifting from ad hoc, individual coping strategies toward collective, institutional, and policy-driven approaches.

By centering the perspectives of journalists in the Arab region, this research contributes to broader debates on AI governance and information integrity in the Global South. It calls for context-aware, language-sensitive, and politically informed frameworks that recognize journalism as a high-risk domain for AI deployment. Without such frameworks, generative AI risks reinforcing existing epistemic inequalities and information disorder. With them, it holds the potential to support more resilient, credible, and public-interest-oriented journalism in the Arab region.

Sources

Arabi Facts Hub. Annual Report 2024: Information Disorder in the MENA Region. Cairo: Arabi Facts Hub, 2024. https://arabifactshub.com/file_upload/1758737037_EN%20Annual%20Report%202024.pdf.

Alghamdi, Emad A., Reem I. Masoud, Deema Alnuhait, Afnan Y. Alomairi, Ahmed Ashraf, and Mohamed Zaytoon. “AraTrust: An Evaluation of Trustworthiness for LLMs in Arabic.” In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Computational Linguistics, 8664–8679. Abu Dhabi, UAE: Association for Computational Linguistics, January 2025. https://aclanthology.org/2025.coling-main.579/.

Al Rayes, Lubana, and Ashraf Elnagar. 2025. “The Need for Robust and Inclusive Benchmarks in Evaluating LLMs on Arabic Text.” In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Natural Language and Speech Processing (ICNLSP-2025), 196–207. Southern Denmark University, Odense, Denmark: Association for Computational Linguistics. https://aclanthology.org/2025.icnlsp-1.20/.

Burgos, Pedro. 2025. “The other AI revolution: how the Global South is building and repurposing language models that speak to billions.” Nature Computational Science 5 (9): 691–694. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43588-025-00865-y.

Buyl, Maarten, Alexander Rogiers, Sander Noels, Guillaume Bied, Iris Dominguez-Catena, Edith Heiter, Iman Johary, Alexandru-Cristian Mara, Raphaël Romero, Jefrey Lijffijt, and Tijl De Bie. 2026. “Large Language Models Reflect the Ideology of Their Creators.” npj Artificial Intelligence 2, Article 7. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44387-025-00048-0.

Costello, Thomas. 2025. “Large Language Models as Disrupters of Misinformation.” Nature Medicine 31 (7): 2092. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-025-03821-5.

Keleg, Amr. 2025. “LLM Alignment for the Arabs: A Homogenous Culture or Diverse Ones?” arXiv, March 19, 2025. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2503.15003.

Koo, Wesley W. 2025. “Cross-lingual Effects of AI-Generated Content on Human Work.” Scientific Reports 15 (Article 30949). Published August 22, 2025. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-16650-w.

Ma, Yulong, Xinsheng Zhang, Jinge Ren, Runzhou Wang, Minghu Wang, and Yang Chen. 2026. “Linguistic Features of AI Mis/Disinformation and the Detection Limits of LLMs.” Nature Communications 17 (Article 456). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67145-1.

Yakhni, Silvana, and Ali Chehab. 2025. “Can LLMs Translate Cultural Nuance in Dialects? A Case Study on Lebanese Arabic.” In Proceedings of the 1st Workshop on NLP for Languages Using Arabic Script, 114–135. Abu Dhabi, UAE: Association for Computational Linguistics. https://aclanthology.org/2025.abjadnlp-1.13/.

Zibin, Aseel, Nabeeha Binhaidara, Hala Al-Shahwan, and Haneen Yousef. 2025. “Metaphor Interpretation in Jordanian Arabic, Emirati Arabic and Classical Arabic: Artificial Intelligence vs. Humans.” Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 12, Article 942. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-025-05282-0.

Mahmoud Hadhoud

Media Expert

Chief Strategic Officer at Open Transformation Lab Inc.

Author of Countering Misinformation in the Digital Age, 2024