Shaping Perceptions: The Impact of Information Disorder on Climate Change Awareness in the MENA

Globally, misinformation and disinformation threaten to undermine climate action, responses to natural disasters, and public support for policies to combat climate change. In 2022, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change stated that disinformation and rhetoric about climate change and the deliberate undermining of science have contributed to false perceptions of the scientific consensus on climate change among the public.

The Middle East and North Africa (MENA) is no exception given its serious exposure to the effects of climate change. In addition to being the most water-stressed region in the world, it is also expected to have the highest average temperature increase compared to any other area, along with an increase in the frequency of extreme weather events, such as flooding, storms, and heatwaves. These changes will pose further pressure on the available limited resources of the region, heightening socio-economic vulnerabilities and worsening environmental degradation.

While organizations and activists are leveraging social media platforms to raise awareness about climate change and natural disasters, information disorder – that is, misinformation and disinformation – around climate change and its co-optation for propaganda risk misleading the public and undermining the urgency of climate action.

Risk of misinformation and propaganda

While social media platforms have the potential to play a critical role in addressing these challenges, they are also fertile spaces for climate mis/disinformation, or deceptive or misleading content that undermines the existence, drivers, and impacts of climate change as well as the urgent need for climate action. This does not just distort the truth – it has real and harmful consequences. While some countries may have stronger initiatives, overall awareness remains alarmingly low, particularly regarding the impacts of climate change on natural resources and in amplifying natural disasters.

When misinformation spreads during a crisis, it can hinder the emergency responses, create unnecessary panic, and divert attention from the real issues at hand. A striking example is the wide spread of misinformation observed during natural disasters where fake videos and photos circulated on social media platforms. For example, Morocco suffered from a 6.8 earthquake in 2023 where it left devastation and loss. Misinformation was highly observed during the aftermath of the event featuring old footage of buildings collapsing in Casablanca, Rabat, and even Turkey. Another example was during Storm Daniel that hit Libya in September 2023. Misinformation proliferated on social media, including false claims such as Tripoli being submerged even though it was not affected.

While the data surrounding targeted disinformation campaigns surrounding climate change are thoroughly under examined in the Arabic language, lessons from the evolution of English-language studies can be used. By evaluating some of the overall sentiments in Arabic, it may lend a deeper understanding to how platforms, organizations, and governments can be more aware of where potential information disorder may flourish.

Climate change discourse on social media

Social media platforms are leveraged in the MENA region by environmental and climate change activists, local organizations, and influencers to spread awareness on local environmental issues. For example, initiatives encouraging reforestation efforts are using social media to raise awareness on the issue of deforestation existing in different countries, such as the UAE’s “For Our Emirates We Plant” initiative and Libya’s Mountain Friends initiative. In countries affected by mounting political instability and conflict, such as Libya, environmental activists are putting in effort to make up for the lack of action by governmental entities to address the serious environmental challenges facing the population.

In addition, these platforms are used to connect grassroot movements and community driven initiatives: for example, Greenpeace MENA’s uses its social media presence on platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter to organize events and promote clean-up and workshops among young people. Moreover, social media platforms allow for real time reporting through images, videos, and OSINT tools such as satellite imagery to track oil spills in bodies of water, deforestation, and other environmental developments around the region. For instance, the April 2024 UAE floods – which drastically impacted Dubai and caused major disruptions of services and the cancellation of flights – saw affected communities use social media to share real-time information in order to provide support and updates about the situation.

The floods, made worse by climate change, also resulted in a slew of disinformation and fake news: a number of conspiracy theories, for example, claimed that the flooding happened in the Arabian Peninsula due to cloud seeding, a weather modification technique meant to change the amount of precipitation. This narrative was widely spread on different social media platforms, forcing numerous leading news sources in English and Arabic to debunk it and also report that the government issued a warning against the spread of rumors and false information regarding the extreme weather events.

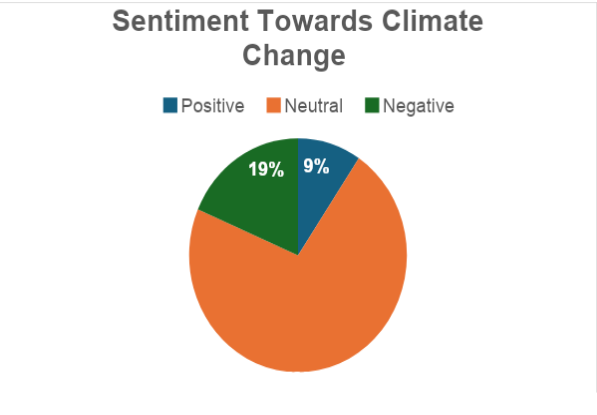

To better understand the discourses around climate change on social media in the Arabic language, particularly between January 2023 and January 2024, data was collected with the support of Meltwater, a media monitoring platform used by analysts, investigators, and fact-checkers to understand the spread of disinformation. The query search retrieved 20K tweets on X, formerly Twitter, related to climate change in the Arabic language. Around 14.2K posts – approximately 72 percent – had a neutral sentiment about climate change, whereas 19 percent were of positive sentiment. Only 3K of the total posts are considered negative.

It is important to understand how this translates in terms of terminologies used and expressions. For instance, the nature of sentiments around climate change online, in Arabic, means that positive posts include expressions of solidarity, motivation, and innovation. Whereas the negative sentiment does not necessarily translate into false information, it could also include expressing fear of the current environmental situation as a result of the impact of climate change, or negative experience related to extreme weather events.

While analysis of social media data shows that posts denying climate change in the Arabic language are low, climate misinformation remains a risk in a region where awareness efforts are a challenge vary from one country to another.

Figure 1: Sentiment of posts retrieved about climate change on X from 01.01.2023 to 01.01.2024 in Arabic

When using X’s advanced search using تغير المناخ AND زائف since:2022-01-01 and until:2024-03-01 in Arabic, results show a relatively low number of tweets pushing climate change denial. One tweet, published on February 22, 2024, claiming that climate change is fake yielded relatively few engagements, generating little engagement. This low interaction rate, specifically in replies and reposts, suggests that this example did not gain significant traction or provoke extensive discussion. Further, this implies that climate change denial may not be a dominant narrative on X, and that such claims are not widely amplified. Nonetheless, the low interaction still shows that some users support the posted narratives which reflect skepticism or misinformation within the Arabic-speaking online community.

Crowdtangle, a now-closed tool made available by Meta to explore and analyze how public content (like articles, videos, or posts) perform on its platforms helped in identifying news channels, Facebook pages, public climate change denial groups, and influential pages. It helps in understanding which pages are amplifying climate change denial narratives and in analyzing how specific articles were shared publicly and how much attention it received on Facebook.

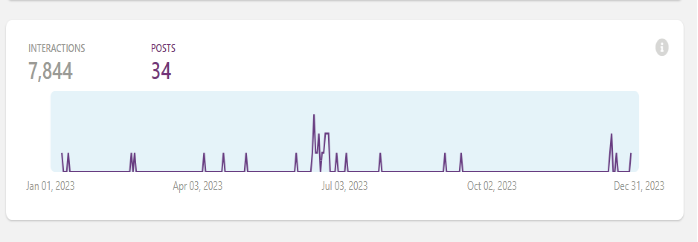

To address information disorder narratives that have been occurring, posts from fact-checking organizations were also examined. From January 01, 2023, to January 01, 2024, 34 posts related to climate change, using the query in Arabic "تغير المناخ" OR "التغير المناخي" OR "المناخ", were published by 24 fact-checking organizations. The query intended to understand different keywords of the term ‘climate change’ in Arabic to highlight the type of narratives of information disorder covered by fact-checking organizations.

Like with the other findings, this limited output could indicate multiple scenarios. First, it suggests insufficient attention to combating and mapping misinformation about climate change on different social media platforms, specifically in Arabic. Second, it could reflect the lack of climate disinformation and misinformation in the region. This could have further implications especially that the MENA region is highly vulnerable to climate change impacts and could open the door to future types of information disorder.

Figure 2: Total posts volume between 01.01.2023 to 01.01.2024 about climate change by fact-checking organizations in Arabic

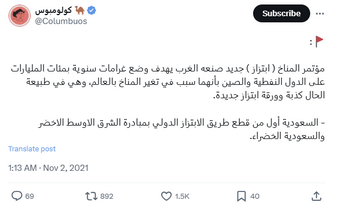

A limited prioritization of this topic even from fact-checking organizations who cover in Arabic (Figure 2) could also reflect a lack of climate disinformation in the region. Using search engine X to identify viral posts on specific skeptic narratives such as "the lie of climate change" in Arabic, the results showed posts pushing for conspiracy narratives about climate change. For example, the X account alfylasofaAzal actively pushes conspiracy theories including climate change, framing climate change as deliberate fabrication or a hidden agenda. Such accounts don’t only distort scientific consensus but also foster mistrust in environmental initiatives. The virality of these narratives indicate their resonance with certain audiences, exacerbating misinformation’s impact on public understanding of climate issues.

If outright denial is not common, then other conspiratorial narratives could misinform or be considered disinformation, posts that accuse cloud seeding by the UAE government as being the cause of heavy rainfall resulting in flooding, causing fear and confusion. The insufficiency in addressing climate change misinformation creates a knowledge gap which has a huge impact on reducing community resilience and delays the action needed to make positive and tangible changes. It also contributes to the lack of understanding of these issues on the local level which leaves limited space for action.

Online narratives around climate change, whether negative or positive, can also sometimes be associated with ulterior geopolitical or propagandistic motives. Some of the X posts with negative sentiment identified through Meltwater included conspiracy narratives denouncing climate change. A post on X described climate change as one of the biggest conspiracies undertaken by the West. The account @sabbanms21, whose bio states ‘’Former Head of the Saudi delegation to the UNFCCC, Former Senior Advisor to the Ministers of petroleum, Author of the blame game. M. of Supreme Economic Council,” pushes rhetoric that climate change is a conspiracy.

The account actively promotes skepticism about climate change, framing it as a geopolitical tool to undermine oil-producing countries such as Saudi Arabia. By blending it with pro-Saudi narratives and positive messages about the oil sector in Saudi Arabia, the account appears to use climate skepticism strategically to align with broader geopolitical objectives. This includes defending Saudi Arabia’s energy policies while questioning climate change initiatives that could potentially limit the oil industry. Another account, a propaganda Russian account with @mog_Russ, with a sizable influence of 487.3K followers heavily pushes anti-western narratives in Arabic in relation to climate change and posted a video of the Belarusian president describing the Conference of the Parties (COP) as a lie.

Although posts with positive sentiment only make up around 9 percent, which is about 1.9K posts, they mainly focus on the shift toward renewable energies and the phasing out of fossil fuels which some countries in the MENA region depend on, including the Gulf states, Algeria, and Libya. In these positive posts, it is equally important to look at the background of the accounts, which may also entail an association with propaganda. For example, the X account The Earth Call, with 62.2K followers, was created in 2017 and disseminates positive sentiments including praising Conference of the Parties 28 (COP28) , held in Dubai, as an inspiring example of climate action. The account belongs to Al-Ain News, a platform owned by International Media Investments and a subsidiary of Abu Dhabi Media Investment Cooperation, which is owned by Mansour Bin Zayad al Nahyan, a member of the Abu Dhabi ruling family. He is also the current vice president and deputy prime minister of the United Arab Emirates.

Conclusion and recommendations

In an era where the digital landscape shapes public perception, the battle against climate change misinformation and disinformation in the MENA region is both urgent and complex. The analysis reveals that while digital platforms are utilized to promote environmental awareness, the spread of climate misinformation and disinformation remains both understudied and a barrier.

In the context of combating information disorder about climate change, experts from leading climate research institutions, media organizations, and policy think tanks have consistently stressed the importance of the efforts undertaken by climate fact checkers and fact checking groups; governments, including the European Union; and international organizations, such as the United Nations. A region like the MENA, which suffers from the impacts of climate change while also dealing with several socio-economic challenges, stands to be the most threatened by the spread of climate change disinformation and misinformation.

Misleading narratives often undermine the science of climate change, reduce trust in scientific consensus, and hinder effective climate action. Thus, addressing climate change in the MENA region requires a multifaceted approach that includes robust information verification, public education, and stronger collaboration between governments, organizations, and digital platforms. By understanding and mitigating the spread of disinformation, we can better equip communities to engage in meaningful climate action and build a more informed, resilient future.